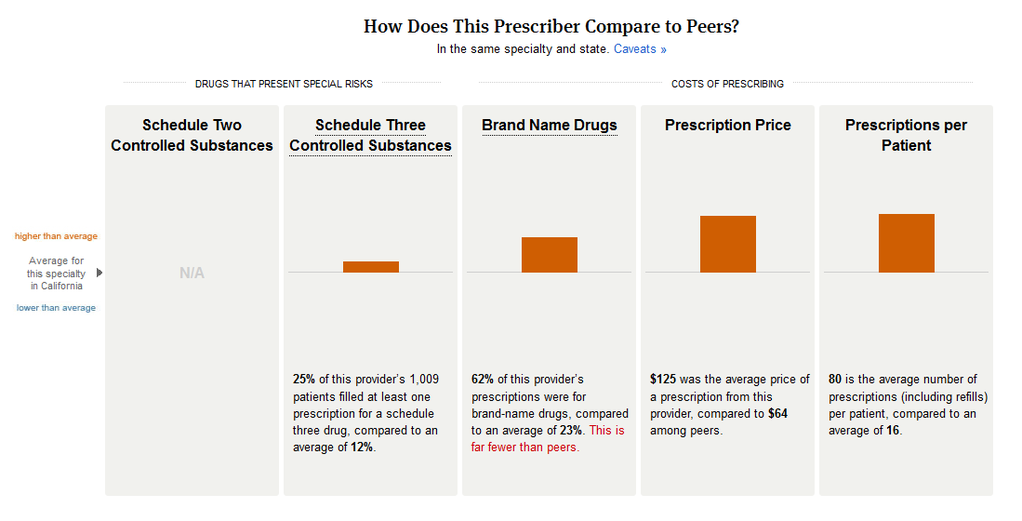

The MacOS has a new self control app called, straightforwardly, SelfControl. The app has an ominous icon, which looks like a cross between a poker game gone wrong and the warning symbol on a bottle of poisonous chemicals:

The app gives users the ability to temporarily block websites, which they know they are wasting too much time on. If you decide, for example, that you keep checking out your Facebook feed rather than finish that important project, you can tell the app to deny you access to the Facebook website for the next, say, four hours.

All of us have limited willpower. And even the act of avoiding Facebook can be exhausting for those people who are addicted to it. This kind of app takes over willpower responsibilities for us, allowing us to use our energy for better purposes.

I’m in favor of the idea, as long as people aren’t spending too much of their time blocking PeterUbel.com!

Want Credibility? Use a Chart!

If I told you there was a new medicine effective in treating a previously untreatable illness, you might be interested. If you have the illness, you might even read up and try to figure out whether the medicine would work for you. Ideally, you will evaluate the strength of evidence – was it a randomized trial; how many patients took the medicine; what is the credibility of the research team?

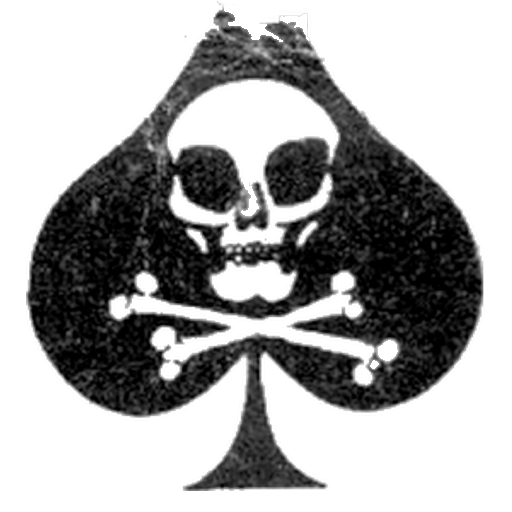

But if somewhere in the midst of that evidence there is a nice graphic, demonstrating how effective the medication is, you will be more likely to believe that the medicine works. That was what a team of researchers led by Brian Wansink found. Here is a graphic – and now I know you will believe that the study was excellent – showing the percent of people who believed the advertising claims with and without an accompanying chart:

We have all heard about “lying with statistics.” Now we know how to persuade with pictures of statistics!

We have all heard about “lying with statistics.” Now we know how to persuade with pictures of statistics!

Does the Thought of Money Make Us Dishonest?

Here is a game you can’t lose. You flip a fair coin ten times and every time it comes up heads, you get $20. Better yet, I won’t even watch you flip the coin, but instead will trust whatever you tell me about the number of times the coin comes up heads versus tails.

Would you be willing to play that game? And if you did play it, would you exaggerate the number of times the coin came up heads?

That was the question Alain Cohn and coauthors asked in a recent study. Cohn made sure participants realized the researchers wouldn’t be able to figure out the actual outcomes of the coin tosses. In other words, participants knew they could cheat and get away with it. In fact, for every person participating in the study, the researchers had no way of knowing whether or not they cheated. Yet the researchers not only uncovered significant cheating, but also discovered that the participants – bankers – were significantly more likely to cheat when they were reminded of their profession.

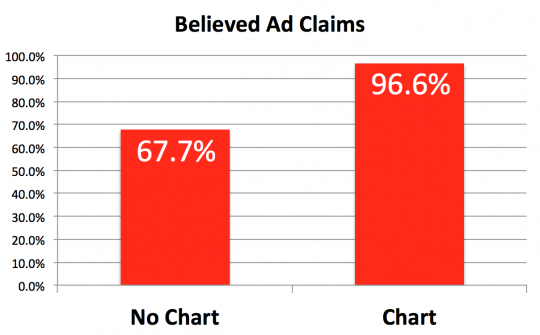

Since Cohn didn’t know the outcome of the coin tosses, how did he know whether participants cheated? He assessed cheating across the group of participants, rather than for specific people. The laws of probability show that when 200 people flip a fair coin 10 times, heads should come up 50% of the time, on average. The laws of probability also enabled Cohn to map out how often all 10 flips are likely to be heads, or how often nine tosses are likely to come up heads, etc.. Here is a picture of what statistics say should have happened versus what actually happened, with the darker bars showing what probability predicts and the lighter bars showing what the participants said happened:

This picture shows that the bankers in this study, on average, cheated just a smidgen, reporting 51.6% heads rather than 50%. In addition, a small number of bankers said the coin came up heads all 10 times, even though statistics says that’s unlikely to happen at all in a population as small as the one that participated in the research.

Taken alone, this finding is not surprising. We know that some people cheat when given an opportunity, but that most people are honest the majority of the time.

But consider what happened when Cohn asked the bankers a series of questions that got them thinking about their careers. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Absolutely Hilarious Nudge!

Is It Fair to Reward Medicaid Patients for Doing What They’re Supposed to Do?

Most conservatives agree that Medicaid costs are too high. Most liberals agree that Medicaid patients should receive necessary medical care for free. And both conservatives and liberals agree that we should embrace ways to encourage Medicaid patients to obtain important preventive care services, in hopes that such services will lower healthcare costs by promoting public health.

But does anyone agree with the idea of paying Medicaid patients to receive such services?

The state of South Carolina has created an incentive program to encourage Medicaid recipients to receive preventive medical care . Show up for an annual exam, and Medicaid patients not only receive the visits for free, but even get $25 a pop for making it to the appointments. Receive mammograms, and they get another $20 per test. Get a flu shot, and they can say hello to an Alexander Hamilton, whose visage adorns the $10 bill.

Here is a table from Kaiser Health News showing what South Carolina plans to offer Medicaid enrollees, depending on which services they receive. There aren’t any huge rewards here, but when you think about the large number of people who are eligible for Medicaid in South Carolina, the cost of these rewards could be substantial:

When I first learned of this reward program, I was reminded of a conversation I had with my teenage son. He had underperformed in school, obtaining grades incommensurate with his ability. I was expressing my disappointment with his lack of effort, but he had a rejoinder: “Dad, you should be rewarding me, for not doing drugs, or drinking and driving like all my friends.”

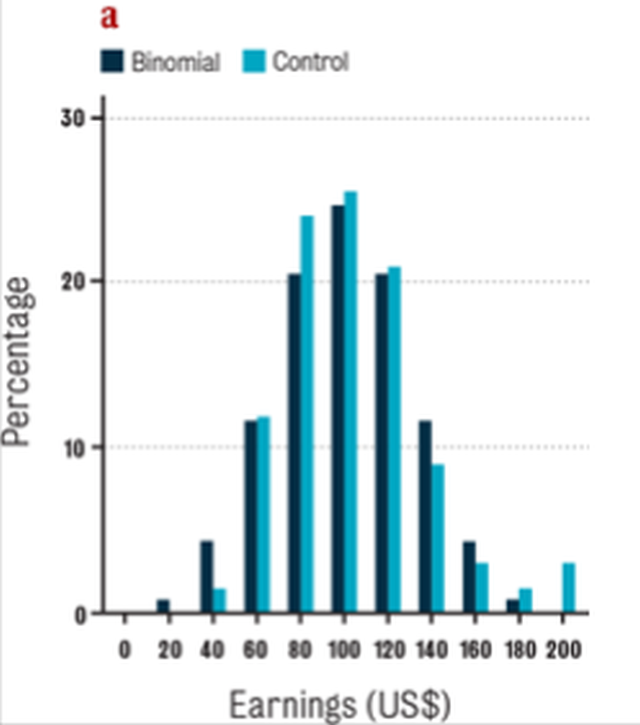

Would This Picture Help You Shop for a Doctor?

More Like a Sludge Than a Nudge

Every once in a while, I post a picture of an effort to nudge people into better behavior. Sometimes, I post pictures of pretty horrendous nudges. In response to one of those posts, Lydia Ashton sent me this picture, of an absolutely, horrendously and horrifically designed “nudge.”

Fortunately, I have determined that if you stare at this for several hours, although you don’t understand the graphic any better than you did at the beginning, a strange calm will come over you, although that may just be the herniation of your brain as it pushes through your medulla oblongata in an effort to get away from the picture.

Fortunately, I have determined that if you stare at this for several hours, although you don’t understand the graphic any better than you did at the beginning, a strange calm will come over you, although that may just be the herniation of your brain as it pushes through your medulla oblongata in an effort to get away from the picture.

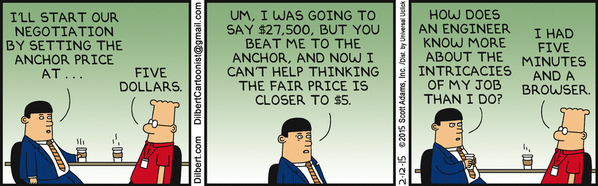

The Anchoring Heuristic Courtesy of Dilbert

Heuristics is jargon used by decision psychologists and behavioral economists to refer to cognitive shortcuts we humans take to make judgments and decisions. One of the first heuristics identified as such by Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky was the anchoring heuristic. I would define it for you, but it is wonderfully captured in this cartoon:

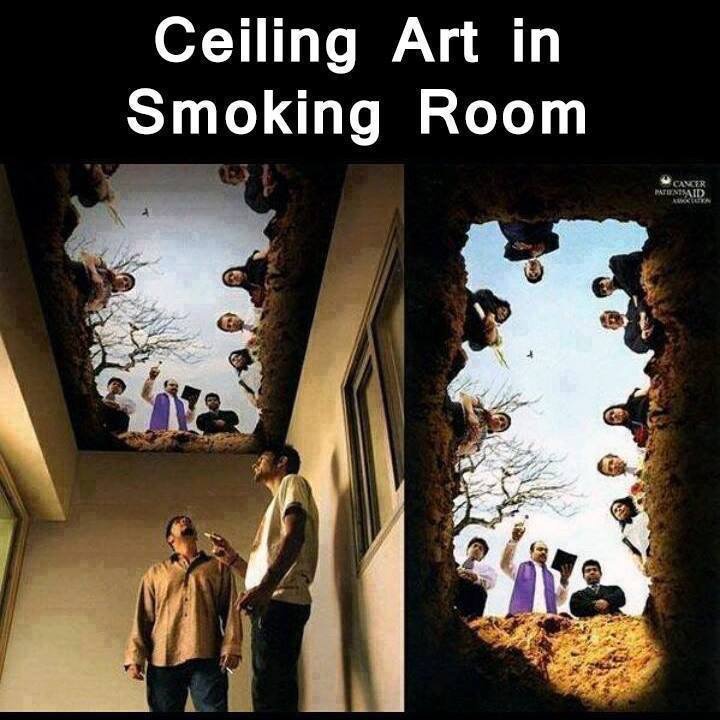

Incentive to Stop Smoking?

In the United States, the FDA tried to mandate that cigarette companies put nasty images of the harms of smoking onto cigarette packages, images that would take up at least half of the carton. It looks like that effort has failed, because the courts have determined that it violates the First Amendment. I wonder what the courts will think about this graphic image, which somebody painted onto the ceiling of a “smoker’s room”.

That’s got to give people reason for pause.

The Hidden Psychology of Antibiotic Prescribing

Experts in decision psychology and behavioral economics have conclusively shown that humans, those silly creatures, are not always rational decision makers. They let unconscious forces influence their thinking, and not always for the better.

But of course, doctors aren’t human. Right?

Well, here is some evidence of just how human we doctors are. The odds of us prescribing antibiotics to our patients varies by the time of day, as we become more or less fatigued: