For my entire life, a half century and counting, healthcare spending in the U.S. has almost always risen faster than inflation. Sometimes it’s relatively slow, sometimes it’s relatively fast, but no matter the time, healthcare spending is climbing. Getting healthcare spending under control is really important for us to do if we hope to have any money left in this country to spend on other important things. You know–like food, shelter, education. That kind of stuff.

So are we in the process of getting healthcare spending under control? A couple recent studies shed light on this question.

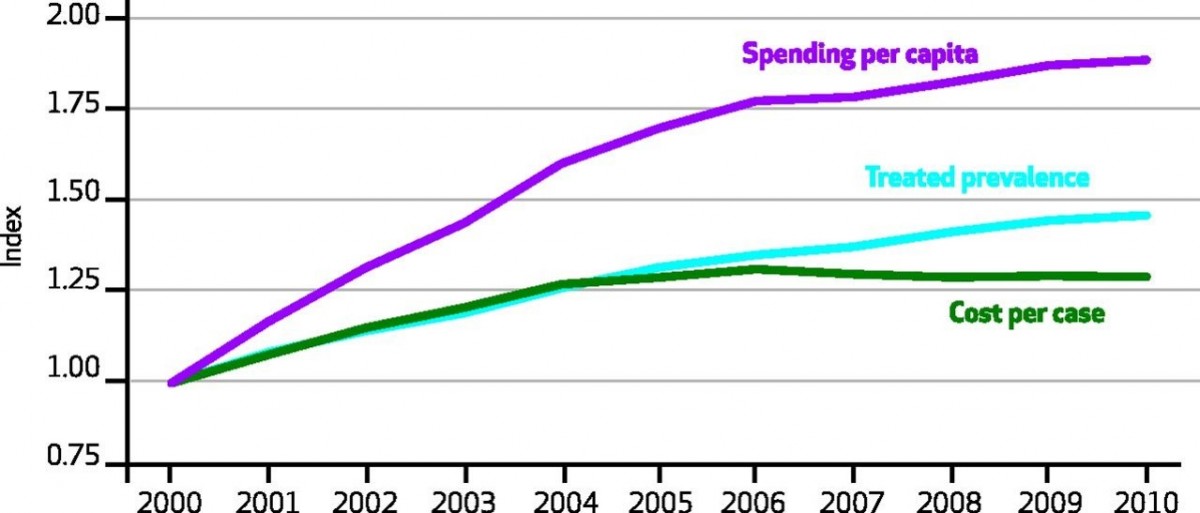

The first comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, an agency within the Department of Commerce. Using a new measure, researchers at the Bureau were able to break down healthcare spending by disease, or at least by a general category of health conditions: cardiology care, for instance, versus cancer care. They looked at two time periods: 2000-2005, a time period of high growth in spending, and 2006-2010, a time of slower growth. They tried to figure out what explained the slower growth in that time period.

Their biggest finding was that the slowing of growth did not occur primarily because fewer people got sick. Growth didn’t slow down, for example, primarily because cholesterol treatment reduced the number of people experiencing heart attacks. Instead, spending slowed mainly because the cost of treating people with problems like heart attacks stopped rising so quickly, what the researchers called the “cost per case” of treatment. Here’s a picture showing that result, with the cost per case line essentially flattening out between 2006 and 2010:

This slowdown in cost per-case spending wasn’t uniform across health conditions. Between 2006 and 2010, care for circulatory conditions grew less than half as quickly as it did between 2000 and 2005. By contrast, the rise in the cost of cancer care didn’t slow one iota over that latter time.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

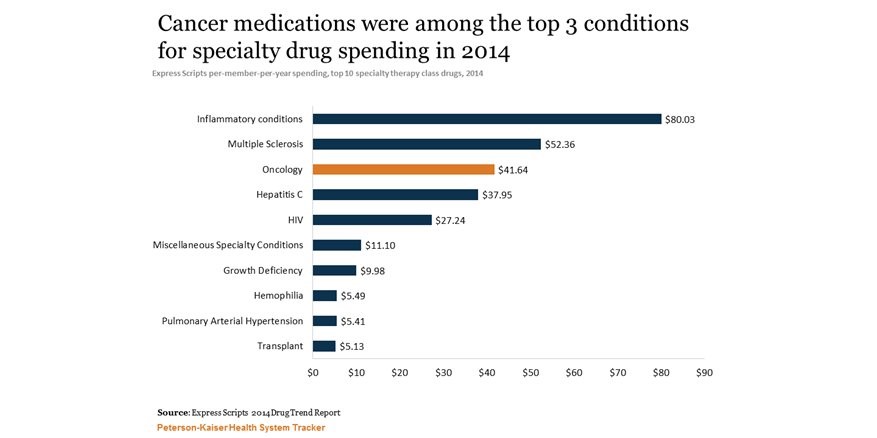

Specialty Drugs at Especially High Prices

There have been many wonderful new medications in the past decade or so, drugs that finally bring hope for many people with serious illnesses like rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and even some advanced cancers. But these drugs often come at a high price. Here is a snapshot of drug spending in 2014, courtesy of the Kaiser Family Foundation:

The Wrong Way To React When Terminally Ill Patients Cry

Just three weeks earlier, she had noticed something strange about one of her breasts. An irregular shape. Her daughter brought her to the doctor, and soon the patient, I’ll call her Amanda, was diagnosed with breast cancer, stage “to be determined.” In fact, she was now in an oncologist’s office, learning what tests she would receive to determine the extent of her tumor. And sitting between her and the doctor was a tape recorder, capturing their conversation.

A dozen minutes into the appointment, Amanda would break down crying. And the physician’s response, which I will lay out for you in a bit, is unfortunately not uncommon. When patients express negative emotion, many oncologists do not respond with empathy. As I’ll explain later, this is an enormous problem, but also one we can fix.

Amanda was 60 years old at the time of the appointment, quite frail for her age, requiring help climbing up onto the exam table because of a recent stroke. She needed to wear adult diapers. She also suffered from diabetes and tremors, although it was unclear whether those non-spontaneous movements were from Parkinson’s or some milder disorder. In other words, her health was already fragile and a breast cancer diagnosis wasn’t going to make things better.

Which may be why she was so distraught about her situation.

The oncologist described how he would evaluate her problem: “Now I am going to order a scan, a CT scan. It’s like an x-ray but she needs to lie down,” he explained to Amanda’s brother. “After that, we will check her blood. After we’ve done the blood test and the scan, I will meet you in one week and we will discuss this, and I will advise accordingly.”

Then, perhaps noticing the look on Amanda’s face, he advised her: “Don’t be scared, please. We will wait for the scan and blood results and see you in one week. So next week, [turning to the brother] please come with your children [one of whom was Amanda’s caregiver] and I can discuss this further.” Amanda’s brother agreed with the plan, but Amanda started crying: “So difficult,” she said.

Her brother tried to intervene. “Stop crying,” he said. The oncologist also stepped into the uncomfortable situation: “Amanda, don’t be scared, please. We don’t know for sure [how bad your cancer is], so let us check first. OK?”

“Doctor will do the best for you,” continued her brother, “so don’t cry. OK?” The physician continued, almost a tag team now with the brother. “Today we can do the blood test. You don’t have to wait after doing that and can go home thereafter.”

“You have a lot of work, right?” she said, apologizing for letting her emotions take up so much of the doctor’s time. He tried to ease her mind. “No,” said the doctor, denying that he was too busy to address her concerns. But he immediately muddled his message. “I mean, you can do your blood tests today.”

A heartbreaking episode, heartbreaking in large part because of the awful situation poor Amanda was in, with so many things she could no longer do because of health problems and now with advanced cancer. Tragic, truly tragic. But compounding this tragedy was a veritable tragicomedy of miscommunication. Amanda breaks down crying and what message does she hear from her brother and doctor?

Stop crying.

Neither brother nor doctor acknowledged that, given her situation, she had a right to be scared, that it would in fact be abnormal not to be frightened. Neither realized that when people start crying, telling them to “stop crying” can actually make patients feel worse. I am sure I have made this same mistake scores of times in my own clinical practice. When a patient cries, our natural instinct as doctors, as humans, is to relieve their suffering, to say something that will stop their crying. It is perfectly normal, even compassionate, to reach out to soothe someone who is crying, to gently tell them not to cry, that everything will be okay.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

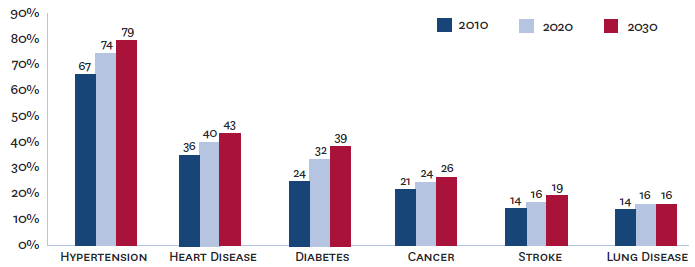

The Future of Disease – in One Picture

Cancer Drugs Aren't As Cost-Effective As They Used To Be

Cancer drugs have become increasingly expensive in recent years. No one blinks anymore when a new lung cancer or colon cancer treatment comes to market priced at more than $100,000 per patient. In part, we don’t blink because we have simply gotten used to such prices – the shock has worn off. Moreover, many of these new treatments are targeted therapies that only work for patients whose cancers express specific mutations, targeting the specific genetics underlying their neoplasms. Because these treatments are targeted, we know that only a subset of patients will receive them, thereby limiting the overall cost of the therapies. We are willing to give pharmaceutical companies some leeway in pricing these drugs, because we recognize that such targeted therapies limit the pool of patients pharmaceutical companies can count on to recoup their investments. In fact, due to such precision targeting, we even hope that the new treatments will be so much more effective against cancers they will justify their high prices.

Unfortunately, a study by David H. Howard and colleagues shows that new cancer treatments, on average, are less cost-effective than older ones. The price of cancer drugs is rising faster than the effectiveness.

In the simplest terms, cost-effectiveness quantifies the ratio between how much an intervention raises healthcare costs and how much it improves health outcomes. For advanced cancers, one important outcome is whether the treatment increases patient survival. A $100,000 treatment that increases life expectancy by an average of, say, six months would have a cost-effectiveness of around $200,000 per life year. (The actual cost effectiveness could differ, depending on how the drug influences other healthcare costs.) That $200,000 per life year cost-effectiveness ratio is on the border of what health policy experts think is worth spending for a year of life. And if that extra year of life is of low quality, the intervention would be deemed even less cost-effective.

(To read the rest of the article, please visit Forbes.)

Which Cancers Do We Spend Most of Our Money On?

There has been lots written lately about the soaring cost of cancer care. You’re spending a lot on cancer recently in part because of many wonderful new treatments that come with a substantial price tag.

But there has been less chatter about which cancers we are spending money on. Here’s a nice picture illustrating that information. I came across it courtesy of Ryan Nipp:

I’d love to see a breakdown of this information as cost per patient. Please let me know if you have access to those data.

What Do Cancer Centers Think Patients Are Looking For?

If you were a cancer center trying to get patients to come to receive care at your facility, what message would you send them? In other words, what would you as a cancer center director think people would value in choosing a place to receive cancer care?

If you were a cancer center trying to get patients to come to receive care at your facility, what message would you send them? In other words, what would you as a cancer center director think people would value in choosing a place to receive cancer care?

One way to answer this would be to survey cancer center directors. You could conduct face-to-face interviews or written surveys. You could hold focus groups, if you could get all the directors in a room together.

But Laura Vater and colleagues from the University of Pittsburgh had a much cleverer and simpler way to answer this question, published recently in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

They analyzed cancer center advertisements. They collected national advertisements from U.S. consumer magazines and television networks, dutifully analyzed the topics covered in each ad, and tabulated the results. What they found is telling, if not totally surprising. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

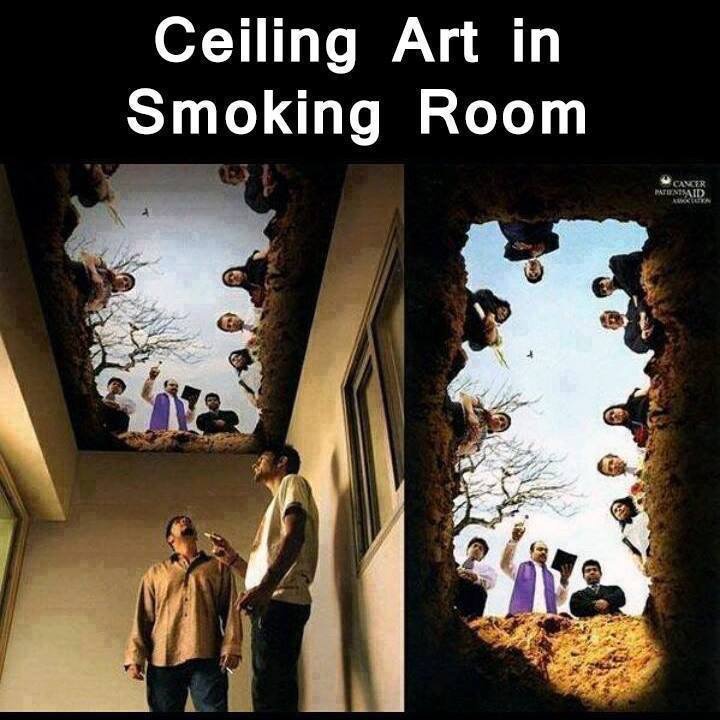

Incentive to Stop Smoking?

In the United States, the FDA tried to mandate that cigarette companies put nasty images of the harms of smoking onto cigarette packages, images that would take up at least half of the carton. It looks like that effort has failed, because the courts have determined that it violates the First Amendment. I wonder what the courts will think about this graphic image, which somebody painted onto the ceiling of a “smoker’s room”.

That’s got to give people reason for pause.

If You Look for Cancer, You'll Find It

What would you like first: the good news or the bad news? Let me start with the bad. Life expectancy among patients in the U.S. with thyroid cancer lags behind that in Korea. In fact, the vast majority of patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer in Korea are cured of that illness, a statement I can’t as easily make about the U.S.

What would you like first: the good news or the bad news? Let me start with the bad. Life expectancy among patients in the U.S. with thyroid cancer lags behind that in Korea. In fact, the vast majority of patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer in Korea are cured of that illness, a statement I can’t as easily make about the U.S.

The good news? Life expectancy among patients in the U.S. with thyroid cancer lags behind that in Korea.

Okay, I kind of pulled a fast one on you. I tried to mislead you into thinking it is bad when cancer patients in another country out-live cancer patients in the U.S. On the surface, living longer after experiencing a cancer diagnosis seems to be a good thing. All else equal, it is better to survive cancer than to die from it.

But all else is far from equal when it comes to thyroid cancer in the U.S. versus Korea. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

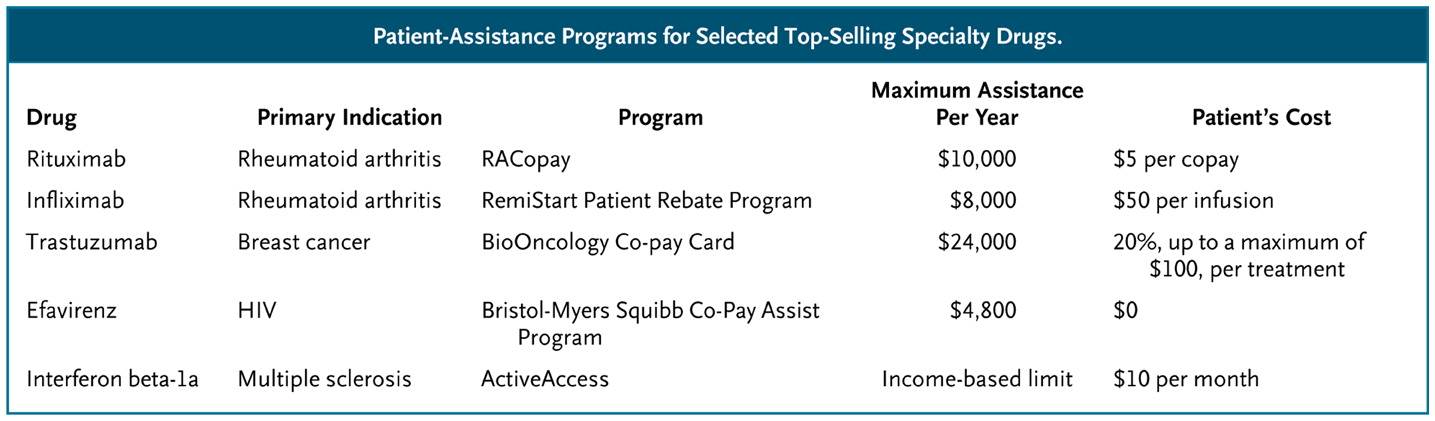

The High Price of Affordable Medicine

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

The high cost of such blockbuster specialty drugs creates significant financial burden for many patients. When a drug costs $90,000 per year, and a patient pays 10% of that cost, we are talking about a serious chunk of change. Not surprisingly, as these out-of-pocket costs rise, so too do the rates of “non-adherence,” medical lingo for “the patients didn’t take the medicines that I, their doctor, thought they should take.” Non-adherence used to be called noncompliance, which sounded too paternalistic. Now some experts are shifting to an even less judgmental language of “medication abandonment.” Indeed, here is a picture of the likelihood that patients will stop taking specialty drugs as a function of their out-of-pocket costs:

What can we do to help patients afford these medications?

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)