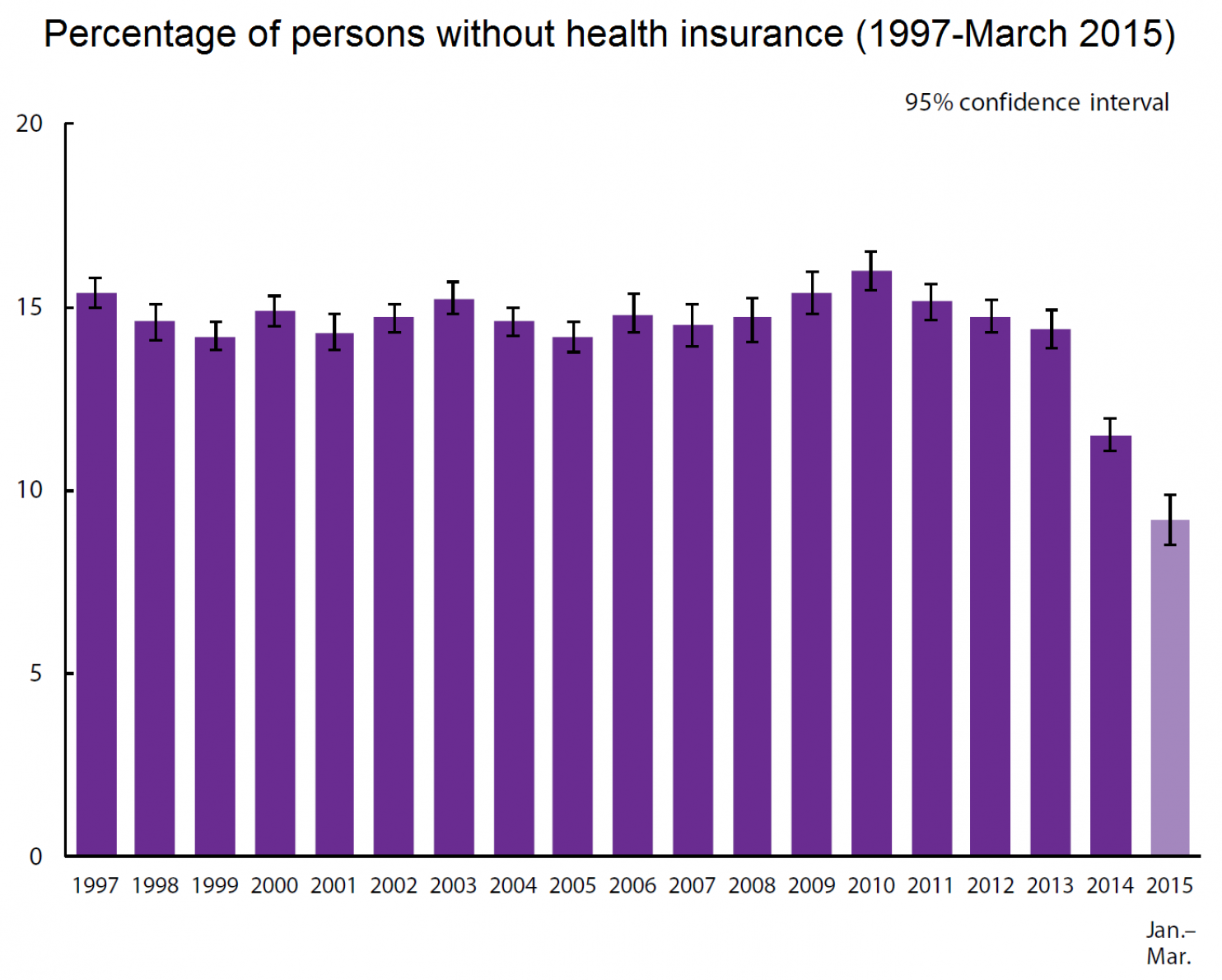

Here is data from the CDC, on the percent of Americans without health insurance. It shows that Obamacare, for all its strengths and weaknesses, is definitely addressing one major problem in the US:

Obamacare Going into a Death Spiral?

Folks around the country are signing up for health insurance right now on the Obamacare exchanges, and some are seeing a very confusing set of options, with price hikes, or maybe not price hikes, and with subsidies, or maybe not such generous subsidies. Here is a great take on what’s happening in NC:

Folks around the country are signing up for health insurance right now on the Obamacare exchanges, and some are seeing a very confusing set of options, with price hikes, or maybe not price hikes, and with subsidies, or maybe not such generous subsidies. Here is a great take on what’s happening in NC:

Obamacare Customers Look for Better Deals as Prices Rise

Cathy Allen pays less than $5 a month for health insurance through Obamacare’s Health Insurance Marketplace. But to keep her plan next year, her costs would have skyrocketed to $150, said her husband, Richard Allen.

Then the Allens got a call from Cumberland HealthNET, a local health care nonprofit, as the staff checked back with people they initially had helped enroll.

“I was glad they did,” Allen said. “She called me and told me to come in and they would try to help us find a better plan.”

After sitting down with a marketplace navigator, the Allens were able to find a plan that would meet her needs for about a dollar more each month.

This is a common scenario for people who already are enrolled in Obamacare plans, say local application counselors and health insurance navigators.

The prices for some Obamacare plans have gone up by double digits, in large part because not enough healthy people have enrolled to help offset the costs of older, sicker enrollees. Some experts see that as a challenge to the long-term viability of the controversial health insurance program.

Most marketplace customers will automatically be re-enrolled in coverage if they don’t actively update their application or change plans by Tuesday. Those who let that date slip by without double-checking their plans may be paying a higher premium come Jan. 1.

“Many people think they are stuck with it,” said Diasmil Pena, a navigator at Cumberland HealthNET. “They don’t know their options.”

In some instances, said Megan Epert, another navigator there, such customers will cancel their plans altogether because they don’t believe they can afford it. Others, she said, get the renewal letter from their health insurance company but assume it will automatically renew at the same rate.

“We’re advising consumers to come on in, check that out, go on the marketplace, to ensure that they’re getting the insurance they want for the premium they want,” said Francine Chavis, a navigator with Legal Aid in Robeson County. Often, there are comparable plans for a lower price, she said.

Janel Lewis, a certified application counselor with Stedman-Wade Health Services, said she’s had success helping existing customers avoid large premium increases.

“We’re seeing that with everyone who brings a notice to us, we’re able to input their information and end up walking out paying less,” she said.

Last year, she said, many customers favored the flexibility afforded by PPO plans offered by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, the only provider to offer plans in every county during the first year of enrollment.

“That made the difference for some people,” she said.

But this year, she said, Cumberland County residents are flocking to United Healthcare.

“You don’t really have as much to choose from,” she said.

Many consumers really like their insurance company, Pena said, “but it’s just unaffordable for them, so they had to end up switching plans.”

For Cathy Allen, an affordable plan meant sticking with United Healthcare. She’ll now have co-payments for doctor appointments, but “it’s better than not having health care at all,” Richard Allen said.

At 57, Cathy Allen has cirrhosis of the liver and other chronic health problems, and before the Affordable Care Act, she had been uninsured, he said.

“If it weren’t for the Affordable Care Act, she’d probably be dead by now,” her husband said.

“Now she’s got it under control.”

Market ‘in flux’

Marketplace consumers are not alone in the seemingly constant change they experience.

“This is a market in tremendous flux,” said Peter Ubel, a Duke University professor specializing in health policy and economics.

“It’s a market that ultimately depends on everybody being in it.”

But many healthy people have been staying away from Obamacare.

“That leaves insurance companies with very expensive enrollees,” he said.

“And so they raise their premiums, and more people wonder if they should buy insurance.”

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, the largest insurer in the state, requested marketplace rate increases averaging nearly 35 percent.

To read the rest of the article, please visit The Fayetteville Observer.

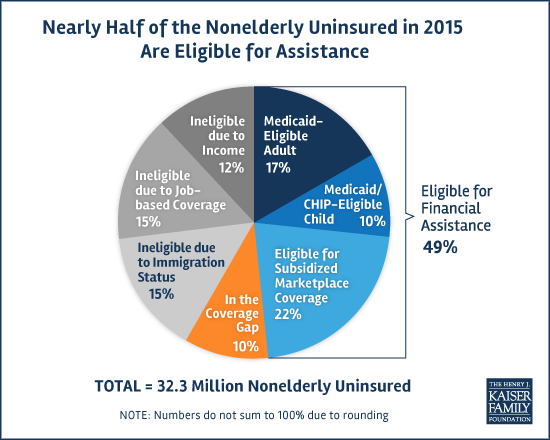

Unnecessarily Uninsured

What Physicians Can Learn from Veterinarians

A while back, I linked to a story by Rebecca Plevin, out of California Public Radio, on the challenge of discussing health care costs. Well, she has tuned up that piece and placed it on Marketplace. Here is a print version:

When a doctor prescribes a medication, most of us don’t ask how much it’ll cost. It makes sense: for a lot of people – both doctors and patients – talking about the cost of care is a totally foreign concept.

Peter Ubel is the perfect person to explain why that is. He’s a physician who now teaches at Duke University, specializing in the overlap of ethics, behavioral economics and medicine.

“Not that long ago, if a person had insurance, they had really good insurance that covered the vast majority of the expenses,” Ubel says. “So there really wasn’t much to talk about when it came to money.”

But these days there’s a lot more to talk about. The Kaiser Family Foundation says last year, 80 percent of people who got insurance through their job still faced an annual deductible that could run as high as $3,000 or more.

That means we all have skin in the game now, Ubel says.

“When the doctor recommends one medication to us, we might have reason now to ask whether another medicine would be almost as good and a lot cheaper,” he explains.

That type of conversation is still rare, but it is happening in at least one medical field.

At Mohawk Alley Animal Hospital in Los Angeles, Dr. Diane Tang examines the mouth of a huge black and white cat named Melvin.

“Tell me a little about what’s going on with Melvin today,” Dr. Tang says to Melvin’s owner, Morgan Bradley. Bradley replies that she’s concerned about a bump on the cat’s face.

Tang lays out testing and treatment options for Melvin.

Then, Kayla Wilkinson, a technician assistant at the hospital, enters the exam room and says something rarely said in a doctor’s office for people: “We have two estimates here,” Wilkinson says, as she walks Bradley through the different options.

Regarding one treatment plan, she adds, “it is most definitely not going to ever get higher than the high point, but just to prepare you, we like to give you a pillow for what to expect.”

Bradley says she appreciates getting this information upfront.

“It always helps in knowing what to prepare for and how much money I’m going to have to scrounge for,” Bradley says.

Dr. Reshma Gupta, an internal medicine physician at UCLA, says the veterinarian model is a good one for the human health care system, but there’s a caveat.

She says doctors and patients can — and should — discuss different treatment options, just as veterinarians do.

“I think where it works is that, when you’re trying to make shared decisions with patients, you come up with all the options that are available for the patient,” Gupta says.

The problem, she says, is doctors who treat people have no way of knowing what those options will cost.

Doctors “do not have access to costs of medications, or commonly ordered labs, or radiology when they’re face to face with a patient,” Gupta says. “And so they don’t have the ability to actually offer that information to patients.”

Ubel, the Duke University professor, says it comes down to one word: insurance. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Marketplace.)

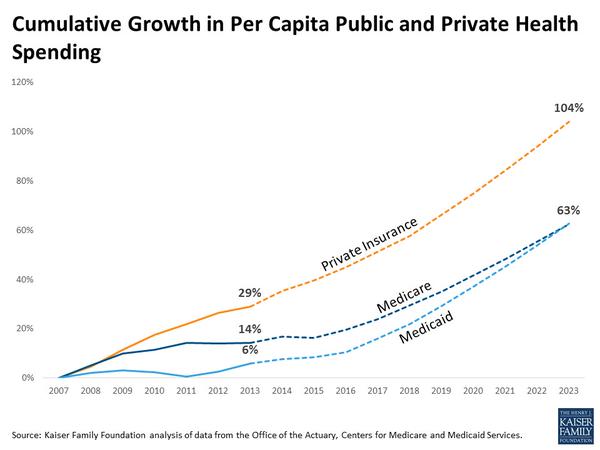

When It Comes to Controlling Healthcare Costs, the Government Outperforms Private Industry

When I think of the federal government, “efficiency” is rarely the first thing on my mind. But when it comes to controlling healthcare costs, we need to consider the possibility that the federal government is better at this job than anyone else. Consider the fact that the United States dwarfs other countries in healthcare spending, despite having a more robust private insurance market than most of our peer countries. Consider this picture, from a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study. It shows a significant rise in private health spending over recent years, especially compared to growth in Medicare and Medicaid:

There’s a lot behind these numbers, much more than I’m going to cover in this short post. But I thought many of you would find these figures interesting.

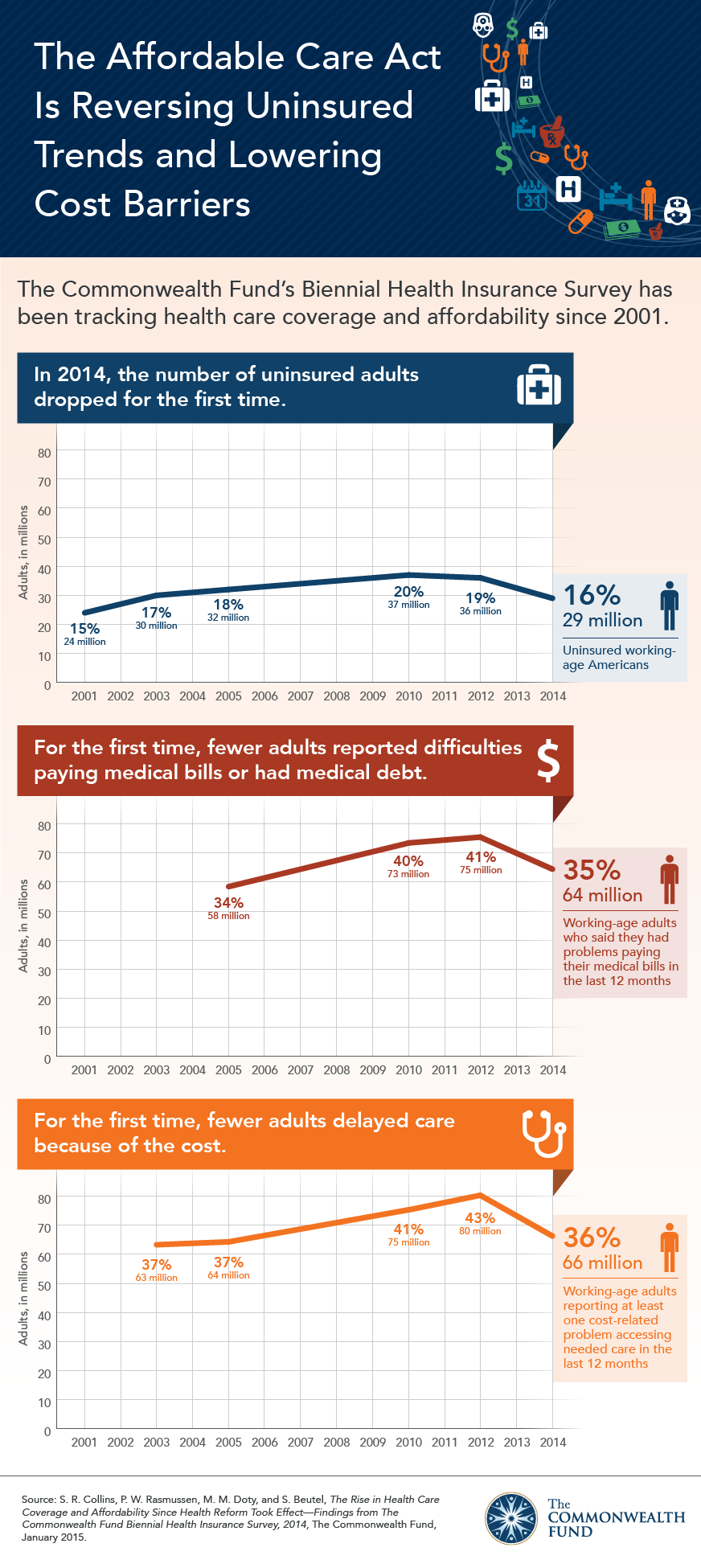

Health Insurance Is About Financial Security Too

People like me, trained to be physicians, have pushed hard to promote health insurance in the United States because we believe, with some evidence to back up our claims, that good health insurance promotes better health. When people don’t have insurance, they delay necessary medical care for too long, and their health suffers as a consequence.

But probably the most direct benefit of health insurance is financial. When people have good health insurance, they are less likely to be burdened by medical costs. That is one of the findings revealed in a recent survey published by The Commonwealth Foundation. Here is a wonderful info graphic illustrating some of their results:

The High Price of Affordable Medicine

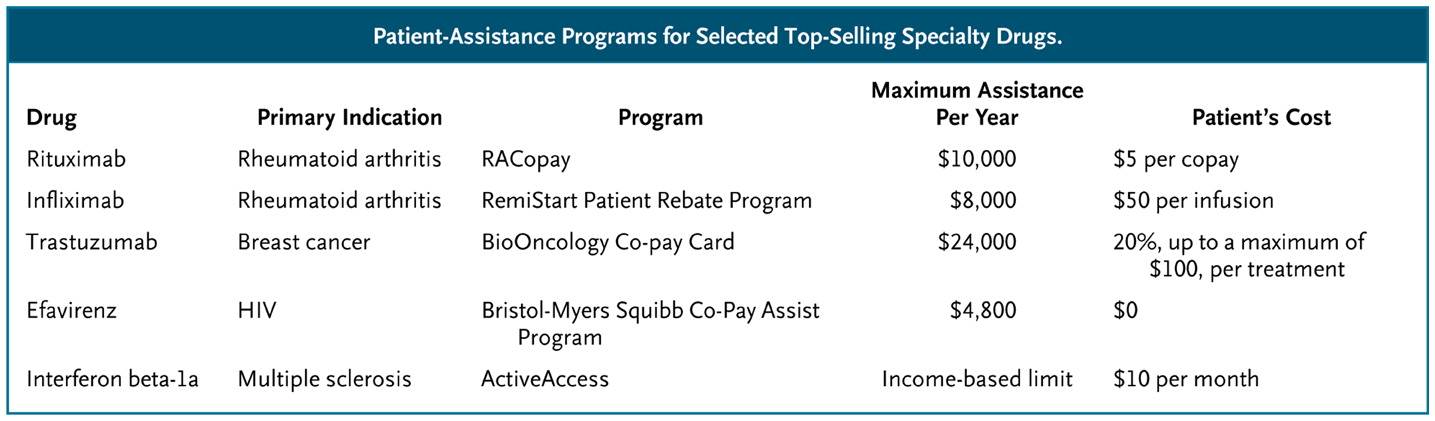

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

The high cost of such blockbuster specialty drugs creates significant financial burden for many patients. When a drug costs $90,000 per year, and a patient pays 10% of that cost, we are talking about a serious chunk of change. Not surprisingly, as these out-of-pocket costs rise, so too do the rates of “non-adherence,” medical lingo for “the patients didn’t take the medicines that I, their doctor, thought they should take.” Non-adherence used to be called noncompliance, which sounded too paternalistic. Now some experts are shifting to an even less judgmental language of “medication abandonment.” Indeed, here is a picture of the likelihood that patients will stop taking specialty drugs as a function of their out-of-pocket costs:

What can we do to help patients afford these medications?

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Healthcare.gov 3.0–Improving the Design of the Obamacare Exchanges

I joined two other, much smarter, colleagues in calling for the use of behavioral economics and decision psychology to improve the design of the websites people use to purchase health insurance in the U.S. That article came out today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here is a taste:

I joined two other, much smarter, colleagues in calling for the use of behavioral economics and decision psychology to improve the design of the websites people use to purchase health insurance in the U.S. That article came out today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here is a taste:

In October 2013, the Affordable Care Act introduced a new insurance market — state and federal exchanges where people can purchase health insurance for themselves or their families. Although the rollout of the exchanges was disastrous, around-the-clock efforts fixed many of the biggest technical problems, and nearly 7 million people purchased insurance in the new market. The second round of enrollment exposed some new problems with the exchange websites — for example, Colorado’s website had difficulty determining whether people were eligible for tax credits — but these problems paled in comparison with those encountered when the exchanges were first rolled out. In short, we have a largely glitch-free system of health insurance exchanges that present millions of people with a robust set of health insurance choices.

Which means that it will soon be time to tackle the much more challenging job of designing exchange websites in ways that maximize the chances that consumers will choose plans best suited to their needs and preferences. If the first round of open enrollment was primarily about avoiding catastrophe and the second round was about ironing out wrinkles in the underlying programming code, then version 3.0, in our view, should focus on redesigning the way exchanges present their insurance choices, to avoid features known to bias people’s decisions.

Obamacare 2.0—Better than Version 1.0?

Paige Rentz, an excellent reporter at the Fayetteville Observer, recently posted a question and answer piece, exploring some of the pressing issues facing the second round of insurance enrollment, on the Obamacare health insurance exchanges. I suggest you look at the entire article. But here is a snippet:

Paige Rentz, an excellent reporter at the Fayetteville Observer, recently posted a question and answer piece, exploring some of the pressing issues facing the second round of insurance enrollment, on the Obamacare health insurance exchanges. I suggest you look at the entire article. But here is a snippet:

What’s at stake?

Last year, North Carolina far exceeded enrollment expectations, with more than 357,000 residents becoming insured through the federal insurance marketplace.

“I don’t know if the stakes are higher than last year,” said Jonathan Oberlander, a professor who specializes in health policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Probably the first time around, it was the most important because we didn’t know how things were going to go.”

He said the Affordable Care Act has some momentum, especially in North Carolina, which outperformed much of the country.

Peter Ubel, a professor at Duke University who specializes in health policy and economics, said he thinks the stakes are much lower.

“I can’t imagine they’ll mess up on the scale they did on the first time.”

Don't Blame Obamacare for Health Insurance Turnover

When the health insurance exchanges began operating last year, critics complained that people were being forced out of their insurance plans. They correctly pointed out that Obama was mistaken to promise that “if you like your healthcare plan, you will be able to keep your plan.” Obama’s promise was wrong not because the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) ripped irreplaceable insurance plans from people. He was wrong because he failed to recognize that the way the insurance industry works in the U.S., people regularly lose their plans.

A study in Health Affairs by Benjamin Sommers (from the Harvard School of Public Health) explored what happened to a nationally representative population of non-elderly people who – ahem, prior to the ACA – purchased insurance without the help of an employer or union. His analysis shows tremendous turnover in health insurance coverage. (Please visit Forbes to read the full article and view comments.)