According to recent research, a hug a day could keep the doctor away. According to another study, twitter can predict the chance that people will experience heart attacks. A normal blogger would look at these two findings and tell a story about the relationship between stress and health. I’m not normal. I looked at these two studies and came to a different conclusion – that we need to change the way we reimburse physicians.

Want to know how I arrived at that view? Let’s start with a quick look at the two studies.

A research team headed by Sheldon Cohen from the University of Pittsburgh exposed volunteers to Rhinovirus particles and monitored them for signs and symptoms of illness, going as far as weighing their nasal mucus. (Isn’t research fun!) Consistent with previous research, they found that people under psychological stress were more likely to become sick, unless they reported having strong social support in their lives. You see, stress creates a neurohumoral cascade, a series of physiologic reactions in the body that impair the immune system. But social support can buffer the immune system.

Even more interestingly, Cohen discovered that hugs – the likelihood that a volunteer was hugged each day – further buffered people’s immune systems, reducing colds even after accounting for the other kinds of social support people received. Hugs are good medicine!

What does this hugging study have to do with physician pay?

In the old days, health care reimbursement was based primarily on the volume of services medical providers provided. Perform one procedure and receive payment; ten procedures and receive ten payments. Perform one annual exam and you’ll be paid for one annual exam, well… you get it. More recently, payers have tried to shift from such fee-for-service payments to pay-for-performance methods. Two doctors might charge Medicare for conducting annual exams on their patients, but if measures show that one does a better job of making sure her patients receive appropriate preventive measures, she will receive higher payments than the other physician. In this case, Medicare would be relying on process measures of care to adjust payments. In other cases, pay-for-performance is based upon outcome measures. For example, cardiac surgeons might receive different levels of pay at the end of the year depending on the survival rates of their patients who undergo specific procedures, after accounting for the severity of patients’ underlying illnesses before the procedure. It’s these outcome-based pay-for-performance measures that are threatened by hugs and tweets.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Why The Government Tried To Fix Primary Care And Failed

Americans spend more per-capita on medical care than just about any other country and, yet, they often have little to show for it. Americans have worse access to care than people in other countries, and are often less likely to receive primary care services, like preventive therapies and screening tests. Determined to address these problems, Medicare leaders have been testing out new models of primary care, hoping to find win-win situations – reimbursement schemes that improve quality while maintaining or lowering the cost of care.

So far, many of those efforts have failed.

Near the end of 2012, Medicare began giving extra money to almost 500 primary care practices across the US, money the practices used to try to improve the care they offered to their patients. The goal of this Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative was to prod primary care practices to make it easier for patients to: contact providers quickly; coordinate care with other specialists; provide care management to patients with complex chronic illnesses; and better engage with patients and their care givers. The extra Medicare payments were decent sized, almost $60,000 per physician per year. The practices could use this money to hire extra nurse practitioners, or to reimburse those who were working odd hours to give patients more access to care, or other efforts.

Medicare not only gave practices these upfront payments, but also offered to give practices extra money if they reduced overall spending for their Medicare population, an incentive known as shared savings.I am a primary care physician and for around 20 years I worked in VA medical centers, a system that, during my time there, did a great job of coordinating care between primary care physicians and sub-specialists, and of offering care management for patients with complex illnesses.

When I practiced in the VA, I often worked closely with pharmacists and nurse practitioners, for example, to address the need of patients with uncontrolled diabetes. So I am very excited that Medicare is trying to invest in and test ways of improving primary care.

Medicare administrators hoped that better primary care would lead to lower costs. Coordinating care with specialists, for example, should reduce unnecessary testing. Better care management should reduce the need for hospital care.

(To read the rest of the article, please visit Forbes.)

Americans Love Their Healthcare But Hate Their Healthcare System — Here's Why

There’s lots to love about American healthcare. We have some of the best clinicians in the world, as evidenced by the huge number of people who come to the U.S. from other countries when they are sick. Yet the American people are less satisfied with their healthcare system than are citizens of the majority of other developed countries.

Why do people in the land of the Mayo Clinic and Mass General Hospital hate their healthcare system so much? In short, many Americans are upset that they cannot afford to make use of all this high quality care when they need it.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Your Physician Can't See You Yet – She's Busy Filling Out Paperwork!

Left to our own devices, most of us physicians try our best to provide high quality care to our patients. But almost none of us provide perfect care to all of our patients all of the time. In fact, many of us get so caught up in our busy clinic schedules we occasionally forget to, say, order mammograms for women overdue for such tests, or we don’t get around to weaning our aging patients from unnecessary and potentially harmful medications.

Because the quality of American medical care is often uneven, third-party payers – insurance companies and government programs like Medicare – increasingly measure clinician performance and reward or punish physicians who provide particularly high or low quality of care.

The result of all this quality measurement: gazillions of hours of clinic time spent documenting care rather than providing it.

According to one study, in fact, clinic staff spend more than 15 hours per week dealing with quality measures for every physician in the practice. In other words, a six-physician clinic group can expect 90 hours of staff time spent documenting quality performance. And it’s not just the staff that are left to do such documentation. Physicians spend precious time in such activities, too. The same study estimates that physicians spend almost 3 hours per week documenting the quality of their care. Here’s a picture of that finding:

Is it any wonder why so many American physicians report being burned out by their jobs?

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Three Things to Know about Future Healthcare Spending

For my entire life, a half century and counting, healthcare spending in the U.S. has almost always risen faster than inflation. Sometimes it’s relatively slow, sometimes it’s relatively fast, but no matter the time, healthcare spending is climbing. Getting healthcare spending under control is really important for us to do if we hope to have any money left in this country to spend on other important things. You know–like food, shelter, education. That kind of stuff.

So are we in the process of getting healthcare spending under control? A couple recent studies shed light on this question.

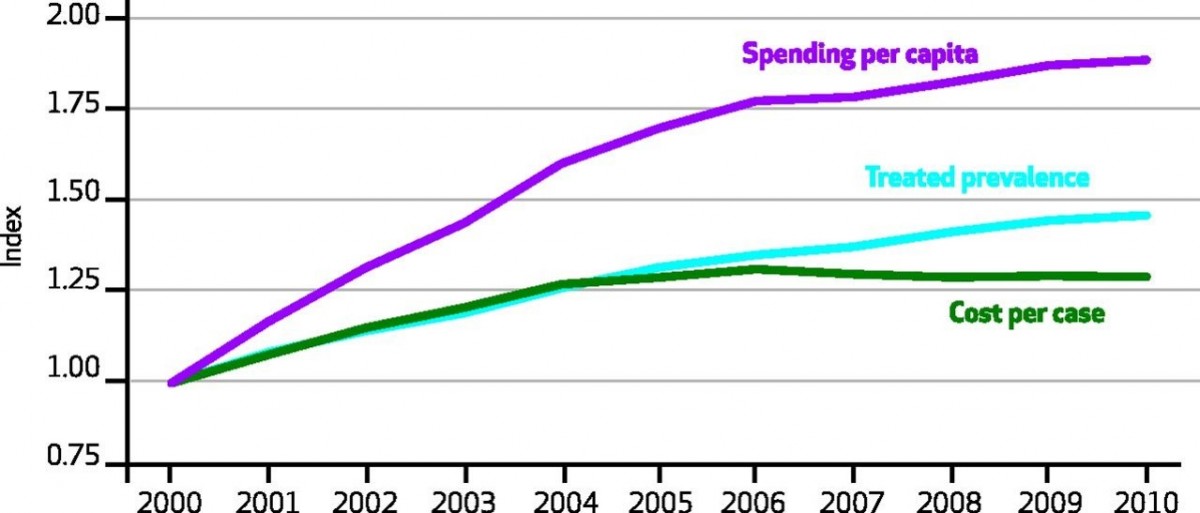

The first comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, an agency within the Department of Commerce. Using a new measure, researchers at the Bureau were able to break down healthcare spending by disease, or at least by a general category of health conditions: cardiology care, for instance, versus cancer care. They looked at two time periods: 2000-2005, a time period of high growth in spending, and 2006-2010, a time of slower growth. They tried to figure out what explained the slower growth in that time period.

Their biggest finding was that the slowing of growth did not occur primarily because fewer people got sick. Growth didn’t slow down, for example, primarily because cholesterol treatment reduced the number of people experiencing heart attacks. Instead, spending slowed mainly because the cost of treating people with problems like heart attacks stopped rising so quickly, what the researchers called the “cost per case” of treatment. Here’s a picture showing that result, with the cost per case line essentially flattening out between 2006 and 2010:

This slowdown in cost per-case spending wasn’t uniform across health conditions. Between 2006 and 2010, care for circulatory conditions grew less than half as quickly as it did between 2000 and 2005. By contrast, the rise in the cost of cancer care didn’t slow one iota over that latter time.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

An Easy (But Politically Complicated) Way To Save Billions Of Dollars On Medical Care

I sometimes worry that my wife Paula won’t be able to see me grow old. Not that I expect to outlive her. She is four years my junior and has the blood pressure of a 17-year-old track star. It’s her eyesight I’m worried about, because she is at risk for a form of blindness called macular degeneration. Paula is the youngest in a long line of redheads, several of whom have been diagnosed with this illness. Her fair-haired grandmother developed macular degeneration and was eventually unable to see her bridge hand and had to give up her golf game, just when she was threatening to score below her age. Fortunately, Paula should be able to avoid her grandmother’s fate, because we now have outstanding treatments for this disease.

Too bad these treatments are costing us billions more than they should. The price of some macular degeneration treatments is staggeringly high, and both doctors and the pharmaceutical company making the treatments are motivated to keep it that way. If we as a country want to forestall blindness in people like my wife, without going bankrupt in the process, we need to pressure our government to do some hardball negotiating.

By way of background, my grandmother-in-law suffered from what ophthalmologists call “wet” macular degeneration. Frail little blood vessels began proliferating in the back of her retina. It’s not unusual to have lots of blood vessels back in the retina. It’s that red blood, after all, that causes so many of us to look possessed in family photos, with red eyes staring demonically into the lens. But in wet macular degeneration, there’s even more blood vessels than normal in the back of the eye, and they are more inclined to leak than typical blood vessels. This leaking fluid damages the nerve cells we depend upon to see light and darkness. For years, there was little doctors could do to slow these leaks.

Then along came Avastin.

Some of you may recognize Avastin as being a cancer drug. That’s true. Avastin works by disrupting a chemical our body makes to promote blood vessel growth. Tumors that depend on new blood vessels to grow are thereby thwarted by the drug. So, too, is macular degeneration. No new frail blood vessels means no blood vessel leakage!

Many ophthalmologists treat wet macular degeneration by injecting Avastin directly into the back of patient’s eyeballs. (Under local anesthesia, of course!) And the drug isn’t even terribly expensive. By one estimate, Medicare pays about $50 a pop for monthly Avastin injections. There is a problem with this effective and affordable treatment, however. Avastin has never been approved by the FDA to treat macular degeneration. Physicians are allowed to use it as an off-label treatment, but because it is off label, it needs to be reformulated by pharmacies into an injectable form, and before standards for such reformulation were bolstered, some patients experienced eye infections from contaminated vials.

Fortunately, there is a second drug to treat macular degeneration, one very similar in its chemical composition, another blood vessel-blocking drug called Lucentis. Unlike Avastin, Lucentis is FDA-approved to treat the disease. That means it is made by the manufacturer in a ready-to-inject formulation, and there is no need for pharmacies to do any additional prepping. Lucentis is just as good as slowing the progression of macular degeneration as Avastin. There’s just one little problem with Lucentis, however. Instead of costing Medicare $50 per pop, it costs up to $2,000.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Here's Why Insulin Is So Expensive, And How To Reduce Its Price

She drew the life-saving medication into the syringe, just 10cc of colorless fluid for the everyday low price of, gulp, several hundred dollars. Was that a new chemotherapy, specially designed for her tumor? Was it a “specialty drug,” to treat her multiple sclerosis? Nope. It was insulin, a drug that has been around for decades.

The price of many drugs has been on the rise of late, not just new drugs but many that have been in use for many years. Even the price of some generic drugs is on the rise. In some cases, prices are rising because the number of companies making specific drugs has declined, until there is only one manufacturer left in the market, leading to monopolistic pricing. In other cases, companies have run into problems with their manufacturing processes, causing unexpected shortages. And in infamous cases, greedy CEOs have hiked prices figuring that desperate patients would have little choice but to purchase their products.

Then there’s the case of insulin. No monopoly issue here – three companies manufacturer insulin in the U.S., not a robust marketplace, but one, it would seem, that should put pressure on producers. No major manufacturing problems, either. There has been a steady supply of insulin on the market for more than a half century. And there haven’t been any insulin company executives I know of who have been hustled in front of grand juries lately.

Yet insulin prices are rising to dizzying heights. In 1991, according to a recent study inJAMA, state Medicaid programs typically paid less than $4 for a unit of rapid acting insulin. After accounting for inflation, that price has quintupled in the meantime.

What explains the gravity-defying cost of insulin? I am not an expert on pharmaceutical pricing, but a few factors go a long way to explaining insulin prices. First, the insulin marketplace has been characterized by continual product upgrades. You see, there’s not just one chemical that makes up all insulin products. Instead, insulin treatments are a family of products, each with slightly different chemical makeup that influences things like how quickly the medicine is absorbed into the blood stream. Manufacturers have been toying with insulin molecules since at least 1936, when the manufacturer added protamine to insulin molecules to extend the duration of the chemical’s activity. In the 1960s, companies began synthesizing insulin, rather than harvesting it from pancreatic tissue. In the late 70s, they began producing insulin through genetic engineering.

So when I said that the price of insulin had quintupled over the decades, we have to keep in mind that today’s insulin is not the same as yesterday’s.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

The Bills People Struggle to Pay

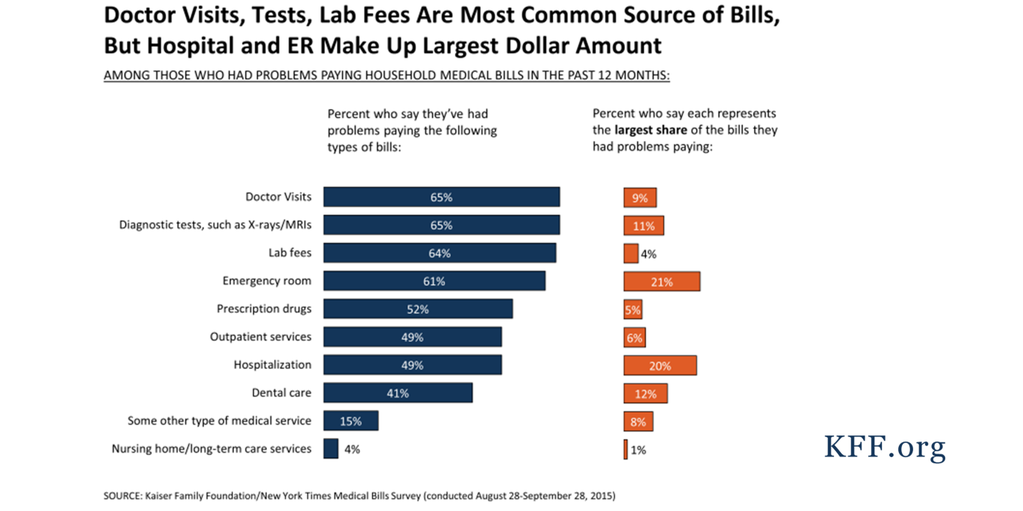

I post pretty regularly on out-of-pocket medical expenses, a topic I’ve been conducting research on, and one that will fit centrally into the new book I’m writing. Most often when people think about paying for medical care, they think about medications. But as this figure from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows, don’t forget about the cost of doctor visits, x-rays, blood tests and, of course, trips to the emergency room:

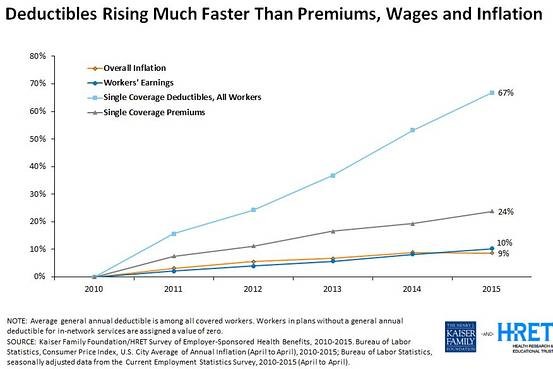

Inflation Crawls While Deductibles Sprint Ahead

With increasing frequency, Americans are purchasing health insurance plans that require high out-of-pocket costs. Chief among those costs are deductibles, the amount of money a person or family must spend out-of-pocket on medical care in a year before their health insurance “kicks in.” As this figure illustrates, from the Kaiser Family Foundation, deductibles have been rising much more quickly than overall inflation, than incomes, and than the cost of their health insurance premiums.

Because of these high deductibles, January and February have become months where many people, when faced with illness, are also faced with burdensome healthcare bills.

Because of these high deductibles, January and February have become months where many people, when faced with illness, are also faced with burdensome healthcare bills.

Rumors of the Obamacare Death Spiral Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

For a while last fall, it looked like the Obamacare health insurance exchanges were spinning towards a death spiral. Enrollment in the health insurance exchanges was not growing as rapidly as many people had hoped. United Healthcare, one of the nation’s largest insurers, announced that it intended to pull out of the exchanges soon, convinced that there are not good profits to be made in that marketplace. The company even decided to cut commissions for insurance agents who direct consumers to the exchange. Some experts warned that the exchanges are entering what policy wonks call a “death spiral,” whereby insurance premiums would rise each year, forcing relatively healthy people out of the market, causing premiums to rise again the next year, and so on.

With a few months of enrollment figures now behind us, it is safe to say that rumors of an Obamacare Death Spiral have been greatly exaggerated. While the health insurance exchanges still face many challenges, they appear to be holding steady, and with a few modest policy changes could transform into a robust marketplace.

The healthcare exchanges were established by Obamacare as places people can go to shop when they don’t receive insurance through their job or through the government. The exchanges are a major method through which the law expands the private health insurance market. But as new markets, they are risky places to do business. With employer-based insurance, insurance companies have had decades to figure out how to price their premiums. But with these new markets, they have been forced to base initial prices on their best guesses of how many people would sign up through the exchanges and, even more critically, of how sick those people would be. If only the sickest of the sick sign up, then premiums need to reflect the high cost of covering their predictably high healthcare needs.

New evidence is out showing just how sick those early enrollees were. But even more importantly, the evidence shows that with the passing of each month, new enrollees have been coming from healthier and healthier stock. If these trends continue, the price of premiums should soon settle into much more affordable territory, and the rise in premiums from year to year should become much less significant.

What evidence supports these conclusions? (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)