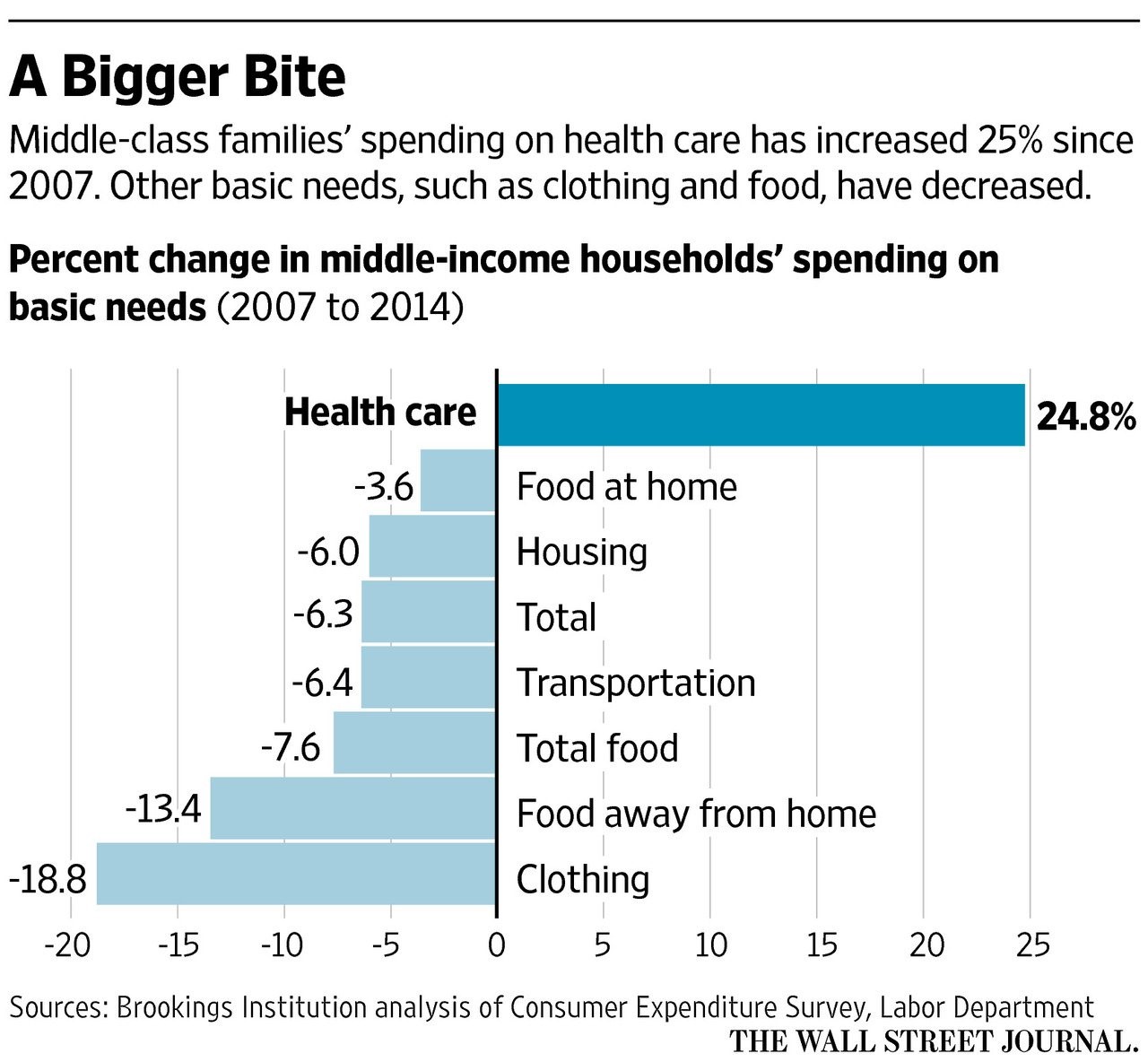

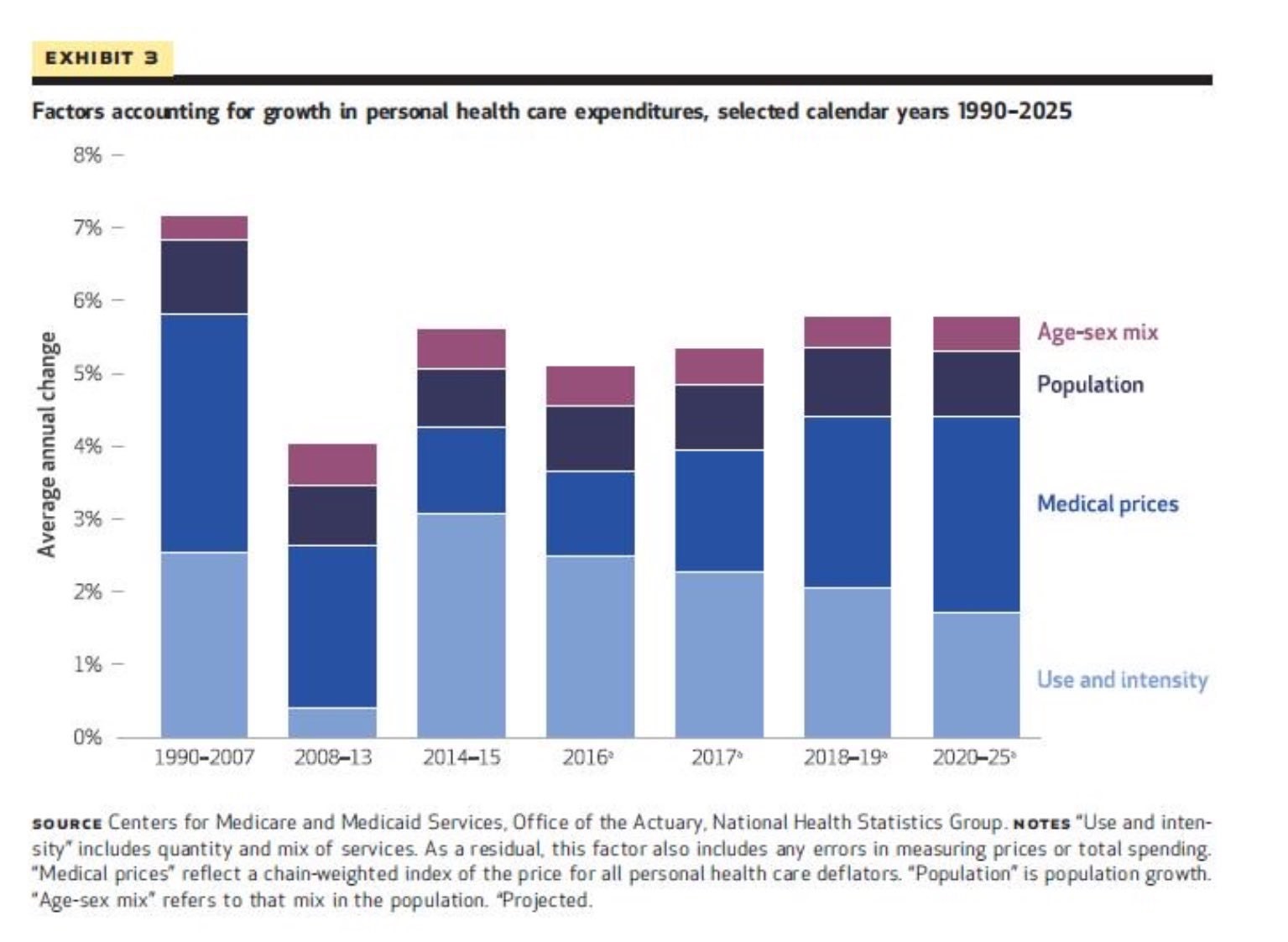

Want to know why we continue to spend so much more on healthcare than other countries? We have a price problem, one that experts predict will play a huge role in future healthcare spending:

If we want to reign in healthcare spending, we must go after high prices. That means taking on physicians, hospitals, pharma companies, device manufacturers…Any politicians ready to do that?

How Companies Can Save Millions on Healthcare Benefits (without Harming Employees)

The free market is supposed to be efficient. Yet employers are throwing away hundreds of millions of dollars, by not giving their employees intelligently designed healthcare benefits that encourage them to shop for affordable lab tests.

Right now, when your doctor orders a CBC (complete blood count) and a basic chemistry panel (checking your sodium, potassium and other fun chemicals), you probably walk down a hallway and get your blood drawn, or maybe you go to the nearest testing site. A pleasant nurse draws several vials of blood from your arm, and eventually you and your employer get a bill in the mail for the cost of your tests. You probably don’t shop around for prices. Yet those tests might cost $30 at one laboratory and more than $100 at another. Who pays that extra $70? A good chunk of that tab will be picked up by your employer, which ultimately makes it harder for your boss to give you a raise. And some of the cost might be on you, with a copay or a charge to your deductible.

There’s got to be a better way.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

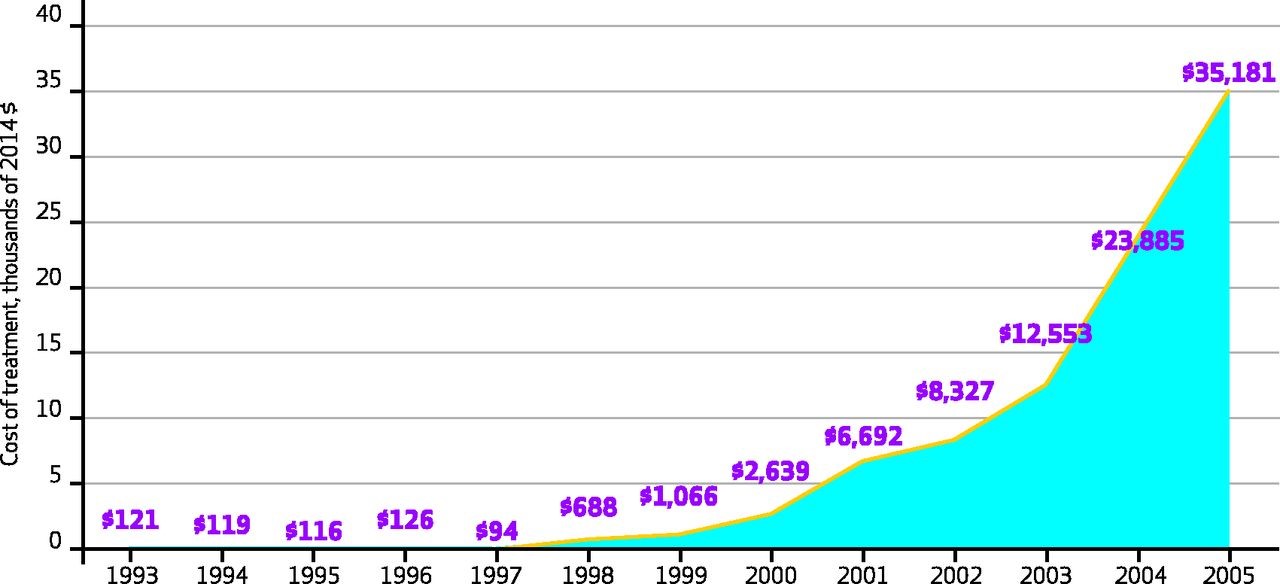

Unsustainable

This picture shows changes in the cost of treating colon cancer, from 1993-2005. It shows unsustainable growth in these expenditures:

By unsustainable, however, I do not mean unjustifiable. Patients with colon cancer have much better prognoses in 2005 than 1993, in large part due to advances in chemotherapy. Instead what I mean by unsustainable is that the rate of growth in spending can’t continue.

If we continue to grow at this rate, we will overwhelm our ability to pay for such care, even if the care continues to improve. We must keep the unsustainability of the spending trend in mind when we set expectations of pharmaceutical executives – and what we look for in the growth of their annual earnings.

We should keep this unsustainability in mind, also, when remembering that healthcare spending threatens the financial stability of governments, corporations, and individual citizens. We should celebrate improvement in treatment for diseases like colon cancer. But we should remember that at some point in time, spending more on such patients, even if it improves their health, might be beyond our means.

Why Trumpcare Is DOA: It Doesn't Address Outrageous Healthcare Prices

Paul Ryan is “excited” that the American Health Care Act, as Republicans call their bill, will trim the federal budget by several hundred billion dollars over the next decade. The 24 million people who are expected to lose insurance under the AHCA aren’t excited about the bill, which will cut government spending at their expense, with potentially fatal consequences for those who go without timely medical care.

Debates over healthcare reform often ask us to pick our poison. We either save money or we save lives.

But these debates ignore an antidote to this poisonous choice. If we tackle high healthcare prices, we can insure Americans at the same time as we curb healthcare expenditures.

This antidote is not theoretical conjecture. In fact, most developed countries provide universal insurance to their residents while spending far less per capita than the U.S. This affordable coverage exists in countries where healthcare payment is socialized, like the UK and Canada, and where it is privatized, like Germany and Switzerland. That’s because all these healthcare systems work to rein in high healthcare prices. As a result, appendectomies cost half as much in Switzerland as in America; and knee replacements cost 30% less in the UK than in the U.S.

Unfortunately, prices have been largely absent from healthcare reform debates in the U.S., whether those reforms are crafted by Democrats or Republicans. It’s true that politicians from both sides of the aisle occasionally speak out about pharmaceutical prices. Both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton criticized pharmaceutical CEOs, like smirking Martin Shkreli, who made the news after enacting outrageous price hikes. But after a public scolding or two, discussion of pharmaceutical pricing usually ends.

Meanwhile, politicians rarely debate the often high price of hospital and physician services in the U.S., which constitute a much larger proportion of healthcare spending than do pharmaceutical products. When is the last time you heard a prominent politician question the lofty incomes of cardiologists, orthopedic surgeons or hospital CEOs?

Perhaps Republicans are hesitant to address high healthcare prices, so as not to galvanize special interests against their current legislation. But the American Medical Association already opposes the Republican healthcare plan, citing the harm vulnerable patients will experience “because of the expected decline in health insurance coverage.” The American Hospital Association also criticized the proposal for not “ensuring that we provide healthcare coverage” to the people dependent on subsidies for their insurance.

(To read the rest of this post, please visit Forbes.)

Costs, Schmosts!

Talk to your doctor about your out-of-pocket expenses. Ask about the cost of your meds. And await for the sound of silence! Sadly, that is too often what happens in medical clinics today. Here is a nice essay, exploring the topic, from a healthcare reporter.

Talk to your doctor about your out-of-pocket expenses. Ask about the cost of your meds. And await for the sound of silence! Sadly, that is too often what happens in medical clinics today. Here is a nice essay, exploring the topic, from a healthcare reporter.

With access to information about the costs of care, patients can make better choices about treatment paths that are aligned with their financial goals. Absent that information—or conversations with their physicians about costs—it’s virtually impossible for patients to incorporate this information into their decision-making.

Herein lies the problem: When physicians don’t talk to their patients about the cost of the care they receive, patients who are blindsided by medical bills may stop showing up for appointments, stop taking medications, and/or decide against pursuing their recommended treatment plans, which reduces the cost of care in the short term but can result in higher costs—for payers, providers, and patients—in the long term.

“We as physicians are trained to try to help patients weigh pros and cons [associated with treatment paths], but we don’t do that well when it comes to costs,” says Peter Ubel, MD, professor of business administration and medicine at Duke University. “Take an ultrasound, for example. A lot of [physicians] think, ‘What’s the downside? It’s a non-invasive test. I’ll just [order an ultrasound] and check the results.’”

What physicians often forget is that the cost of that ultrasound—which could be as much as $500—can “invade our patients’ wallets,” he says.

To read the rest of this article, please visit the Modern Medicine Network.

Medicare Is Reducing the Cost of Knee Replacements (Here's How That Could Backfire)

Knee replacements are booming. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of knee replacement procedures in the United States doubled, to more than one million. Experts think the figure might rise sixfold more in the next couple decades, because of our aging population. Since many people receiving knee replacements are elderly, Medicare picks up most of the cost of such procedures. In response to this huge rise in expenditures, Medicare is experimenting with ways to reduce the cost of procedures. But that raises a disturbing possibility. If orthopedic surgeons make less money on each knee replacement they perform, they might start performing unnecessary procedures.

Consider Medicare’s recent experiments with reimbursing knee replacements according to “bundled payments.” Under such reimbursement, Medicare gives healthcare organizations a lump sum to cover the cost of a knee replacement–not just the cost of the operation but also the cost of post-operative x-rays, physical therapy, even time in nursing homes or rehab hospitals. Before bundled payment, providers would receive separate payments for each of these services, meaning inefficient providers might take more x-rays than necessary, or keep patients in rehab hospitals longer than they needed such comprehensive care, and be rewarded for this inefficiency by receiving additional payments. Under bundled payment, Medicare tracks all the knee-replacement costs for a given patient, over a 90-day period. If a patient incurs fewer expenses than expected, Medicare gives the providers part of these savings back as a reward. (Warning–this is a very oversimplified description of bundling.)

Early evidence suggests that bundled payments reduce the cost of knee replacements by an average of almost $1,200 per procedure. With a million such procedures performed in a year, that reduction could save over $1 billion. Moreover, these savings don’t seem to come at the expense of quality, at least as far as we can tell. (Quality measurement in healthcare is notoriously difficult.) For example, when knee replacements were paid for through bundled payments, there was no subsequent increase in readmission to the hospital or emergency room visits among patients whose procedures were reimbursed according to bundled payments. Same quality at a lower price–who could be against that?!

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Are Your Healthcare Prices Outrageous? Here's What Happens When Prices Come Out Of The Dark

They both had shoulder pain, persistent despite weeks of physical therapy. Both received MRI examinations at reputable radiology facilities, looking for things like rotator cuff tears, labral disruptions and other anatomical abnormalities. What was different was the price they paid for the MRI, with one patient paying $1000 more than the other. Welcome to the crazy American medical marketplace!

Health care prices in the US vary substantially across providers, in part because those prices are so often opaque. When primary care physicians order MRIs for their patients, for example, few patients shop around for affordable radiology centers. There is no reason to shop, because most probably wouldn’t find out what the price was anyway.

That may soon change, if promising results from a recent experiment hold true. The experiment was launched by AIM Specialty Health, an insurance-like company that tries to manage the cost of expensive tests and procedures. The company decided to call patients up on the phone whenever the patients had scheduled MRIs that were either substantially more expensive than competing providers, or were going to be performed by a radiology group rated as significantly lower in quality than its competitors.

After receiving these phone calls, some patients shrugged their aching shoulders and went to whichever facility they felt like going to, realizing they weren’t going to pay out-of-pocket for their MRIs anyway. For example, if a patient had reached her out-of-pocket maximum for the year, then going to a high priced MRI facility would not affect her pocketbook. So she might stick with her originally scheduled test. But other patients, once they learned about the price and quality of alternative providers, canceled their originally scheduled scans and rescheduled with a competitor.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Rare Diseases Are Becoming Too Common. Sound Impossible? Here's Why It's Not

It is hard to make money treating rare diseases. There simply aren’t enough customers to generate many profits. That’s why the U.S. government passed the Orphan Drug Act in 1983, a law which created a series of incentives to encourage drug companies to develop treatments for rare or “orphan” diseases – conditions affecting less than 200,000 people in the U.S. Thanks to longer patent protection, tax reductions, and fee waivers, the orphan drug industry has become quite profitable.

Are rare orphan diseases now becoming too common?

In the 1980s, the pharmaceutical industry received orphan drug status for about 3 or 4 products per year, with most of these drugs being either the first treatments available for the diseases in question or major improvements over prior treatments. From 1983 through 2010, the pharmaceutical industry never received approval for more than 10 orphan drugs in a given year.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Americans Love Their Healthcare But Hate Their Healthcare System — Here's Why

There’s lots to love about American healthcare. We have some of the best clinicians in the world, as evidenced by the huge number of people who come to the U.S. from other countries when they are sick. Yet the American people are less satisfied with their healthcare system than are citizens of the majority of other developed countries.

Why do people in the land of the Mayo Clinic and Mass General Hospital hate their healthcare system so much? In short, many Americans are upset that they cannot afford to make use of all this high quality care when they need it.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)