Aggressive control of blood pressure has saved millions of lives, and has prevented millions of people from experiencing heart attacks, strokes and kidney failure, among other things. Admittedly, controlling blood pressure is not the sexy part of medical care, but when primary care doctors like me help people get their blood pressure under control, we do just as much good as any of our colleagues who practice as cardiovascular surgeons. (No offense to those surgeons, of course, who do worlds of good for their patients!)

But blood pressure reduction can be too much of a good thing. For example, when patients with diabetes receive overly aggressive blood pressure treatment, the harms of that treatment–the side effects of low blood pressure–loom larger than the potential benefits. And I’m not talking just side effects like feeling a little bit fatigued from taking the pill. Aggressive blood pressure treatment can increase the risk of hazardous falls, for example. Consequently, physicians sometimes need to take their foot off the gas, and reduce the intensity of patients’ blood pressure medications. Unfortunately, a study from JAMA Internal Medicine shows that doctors frequently have difficulty backing off. The study looked at diabetes patients and assessed whether doctors reduced the intensity of hypertension treatments when people’s blood pressure dropped below recognized thresholds. They also looked at whether doctors reduced the intensity of patients’ diabetes medications, when their blood sugar levels–their A1C results–got worrisomely low. In looking at how aggressively doctors treated patients, the researchers also estimated how long patients had to live, based on their age and how sick they were. They estimated this because someone in the last, say, five years of his life is not going to get much benefit from aggressive blood pressure or diabetes control, because of the benefits of such control (versus more moderate control) accrue over many years, while the harms, the side effects, happen much more quickly.

The researchers discovered that physicians had a hard time backing off on, “de-intensifying,” aggressive treatment. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Is It Rational for Breast Cancer Patients to Have Bilateral Mastectomies?

Warning: I am not writing about Angelina Jolie. I am not asking whether women like Jolie, with a strong family histories of breast cancer and known genetic mutations, should consider having bilateral mastectomies. Women like Jolie face extremely high lifetime risks of breast cancer, and thus must make difficult decisions about whether to receive prophylactic mastectomies – surgical removal of healthy breasts in an effort to prevent them from harboring future cancers. I’m not writing about people like that.

Instead, I am writing about women who actually have been diagnosed with breast cancer, but who do not have any known genetic mutation predisposing them to such tumors. I’m wondering in these cases: Is it rational for women to ask their doctors to not only remove the affected breast, but also to perform a contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (hereon: CPM) – a procedure to remove the unaffected breast?

I will tell you my answer right now, so I can walk you through my reasoning without misleading you as to my intentions. I think the decision whether to receive CPM is a very difficult one. Unfortunately, many women make this decision even though they are poorly informed about the pros and cons of the procedure. Given what they believe about CPM, it is totally rational to receive that procedure. But if they were better informed? Then, honestly, I’m not sure so many women would receive that procedure.

But I might be wrong. I expect that CPM decisions, like many decisions most of us make in our lives, are often influenced by highly intuitive thought processes, ones often not influenced by informational campaigns. In short, I refuse to call this decision rational or irrational. Instead, I see it as a really hard call. But it’s a hard call we need to understand, because of what it tells us about the challenges of making good medical decisions.

Let’s start with the information that, plausibly, ought to guide such decisions. When women without genetic mutations (hereon: non-carriers) experience cancer in one breast, their risk of experiencing a cancer in the other breast is usually not dramatically different from the general population risk. To put a number on that: studies put the 10 year risk of contralateral cancer at about 5%. And with new breast cancer treatments, that risk has declined even further. So we are talking about an annual risk of less than a half a percent per year.

A second fact of note: there is no evidence, none, that CPM reduces a woman’s chance of dying of breast cancer. With such a low risk of a contralateral cancer arising, and such aggressive monitoring of such cancer in women with breast cancer histories, most such cancers are found at very early and very treatable stages.

This last fact is important to keep in mind when we look at why women choose CPM. According to a recent study in The Annals of Internal Medicine, more than 90% of women who receive CPM say they did so to increase their chance of long-term survival. Indeed, the majority of non-carriers who receive CPM significantly overestimate the impact the procedure will have on their risk of breast cancer recurrence, and on their chance of long-term survival.

In other words, many CPM decisions are either uninformed, or are being influenced by misperceptions. This finding is concerning given the dramatic rise in CPM rates in recent years. Back in the 90s, less than 5% of non-carriers received CPM after breast cancer diagnoses. Today, that figure is approaching 25% in many cancer centers.

I am in no way prepared to say that women who receive CPM are making poor choices. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

In Medical Market, Shoppers Lack Savvy

Even before Obamacare became the law of the land, the U.S. health care system was undergoing a dramatic transformation. Millions of people were shifting from generous health insurance plans to consumer-directed ones that pair low monthly premiums with high out-of-pocket costs.

Even before Obamacare became the law of the land, the U.S. health care system was undergoing a dramatic transformation. Millions of people were shifting from generous health insurance plans to consumer-directed ones that pair low monthly premiums with high out-of-pocket costs.

This shift has been encouraged by employers, eager to reduce the cost of employee benefits. It has also been encouraged by market enthusiasts who contend that the U.S. health care system needs to be more like the traditional consumer economy.

In theory, a family with a high deductible plan – on the hook for, say, the first $5,000 of health care expenses each year – will scrutinize the cost and quality of health care alternatives before deciding whether to receive them. In practice, health care consumerism doesn’t always play out at the bedside in ways that promote savvy medical decisions.

That was one of the conclusions my colleagues and I drew after studying more than 2,000 medical appointments – typewritten, verbatim transcripts of doctors and patients interacting in outpatient clinics across the country. The results, which appear in a study released this week by Health Affairs, should raise a cautionary flag about venturing further into the tricky terrain of health care consumerism.Consider one of the breast cancer patients in our study who was still being evaluated to determine the extent of her tumor. Because she had no strong family history of the disease, the doctor cautioned that her insurance company might not agree to pay for the expensive genetic testing. “How much does it cost if I have to pay for it?,” the patient asked. “Oh we don’t want to talk about that,” the doctor replied, thereby putting an end to her attempt to become an informed consumer.

Or consider the patient who mentioned she “cannot take my pills because there is now a co-pay.” When she explained that she had “zero income,” the physician replied, “That’s what happens, yeah,” without addressing her inability to pay for the medications.

Health care consumers – aka “patients” – cannot expect to make savvy financial decisions if their doctors don’t engage with them in productive conversations about the pros and cons of their health care alternatives, including the financial costs. Some physicians say they are reluctant to do so because money talk would contaminate the doctor-patient relationship. Many more physicians, I expect, would like to hold such conversations, but struggle to do so because there’s no easy way to figure out how much patients will be required to pay out-of-pocket for their medical care.

The U.S. health care system is mind-numbingly complex. Some patients have private insurance, others have Medicare or Medicaid. Some with private insurance face high deductibles, others low. Some Medicare patients purchase supplemental insurance, others don’t. To make matters even more complicated, each of these payers has different rules for deciding what services to cover, and how generously to cover them.

In fact, frustration with our system often distracts physicians from dealing with patients’ financial concerns. For example, after one patient in our study complained about the cost of a bone drug, the doctor acknowledged the price was “crazy” and then went on a rant: “What usually happens is the hospital or clinic will charge 300 times what they think they can get and the insurance company pays 1/20th of the original. It’d be like going to your car mechanic and them saying, ‘It’s going to be $17,000 to get this fixed,’ and you say,’ Well, how about $149?’ ” He went on to complain about the high salary of an insurance company CEO, and never returned to the patient’s difficulty paying for her medication.

There are steps we can take to improve this. Medical schools should teach students how to navigate the new world of health care consumerism. We also need to make it easier for patients and physicians to discern the cost of medical care by having more states pass legislation like Massachusetts and North Carolina that requires providers to publish health care prices. These are promising developments.

But we should not delude ourselves into thinking that price information alone will transform patients – frequently overwhelmed by their health care conditions – into super shoppers. Until health care consumerism can function in a manner that begins to achieve its promise, we should be cautious about pushing more people into health insurance plans that force them into a consumer role that they and their physicians are not yet ready to embrace.

***This op-ed was previously posted in The News & Observer***

Reducing Healthcare Waste: Don’t Expect Patients To Take The Lead

Lena Wright’s best friend was hunched over like a character from a French novel, with spinal bones so thin they would fracture with a fit of sneezing. Determined to avoid that fate, Wright (a pseudonym) asked her primary care doctor to test her for osteoporosis with a DEXA scan, also known as Dual Energy X-ray Absorption. The scan would send two X-ray beams through her bones, one high energy and the other low. The difference in how much energy passes through her bones would somehow (the wonders of physics!) allow her doctors to calculate the thickness of her skeleton.

If you need to figure out whether you have osteoporosis, a DEXA scan is a good idea. But if you don’t need such a scan, you end up exposing yourself to harmful radiation and, of course, to an unnecessary healthcare expense. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, most people do not need the test, because they do not have risk factors for osteoporosis. Lena Wright, for example, harbored no family history of osteoporosis, had exercised regularly her whole life, didn’t smoke or drink and, very importantly, had received the test five years earlier at age 65, which showed her to have normal bone density at the time. In the best judgement of medical experts, a DEXA scan would bring Wright more harm than benefit.

But she was worried. So her doctor, to ease her anxieties, ordered another scan.

What, if anything, can we do to reduce unnecessary and potentially harmful medical testing?

We can start by trying to reduce patient demand for such services. That is an approach taken by the Choosing Wisely campaign, a voluntary effort by medical professionals to reduce wasteful medical care. As part of this effort, professional societies like the American Academy of Family Physicians put together “top 5” lists of wasteful services. Then, in partnership with organizations like Consumer Reports, they’ve tried to educate the general public about why they should be happy to avoid such services.

I am a huge fan of educating the general public and think that Consumer Reports does as fine a job at this as anyone in the business. But I also recognize that their reach – their ability to get the word out to the masses – is limited. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

The Wrong Way To React When Terminally Ill Patients Cry

Just three weeks earlier, she had noticed something strange about one of her breasts. An irregular shape. Her daughter brought her to the doctor, and soon the patient, I’ll call her Amanda, was diagnosed with breast cancer, stage “to be determined.” In fact, she was now in an oncologist’s office, learning what tests she would receive to determine the extent of her tumor. And sitting between her and the doctor was a tape recorder, capturing their conversation.

A dozen minutes into the appointment, Amanda would break down crying. And the physician’s response, which I will lay out for you in a bit, is unfortunately not uncommon. When patients express negative emotion, many oncologists do not respond with empathy. As I’ll explain later, this is an enormous problem, but also one we can fix.

Amanda was 60 years old at the time of the appointment, quite frail for her age, requiring help climbing up onto the exam table because of a recent stroke. She needed to wear adult diapers. She also suffered from diabetes and tremors, although it was unclear whether those non-spontaneous movements were from Parkinson’s or some milder disorder. In other words, her health was already fragile and a breast cancer diagnosis wasn’t going to make things better.

Which may be why she was so distraught about her situation.

The oncologist described how he would evaluate her problem: “Now I am going to order a scan, a CT scan. It’s like an x-ray but she needs to lie down,” he explained to Amanda’s brother. “After that, we will check her blood. After we’ve done the blood test and the scan, I will meet you in one week and we will discuss this, and I will advise accordingly.”

Then, perhaps noticing the look on Amanda’s face, he advised her: “Don’t be scared, please. We will wait for the scan and blood results and see you in one week. So next week, [turning to the brother] please come with your children [one of whom was Amanda’s caregiver] and I can discuss this further.” Amanda’s brother agreed with the plan, but Amanda started crying: “So difficult,” she said.

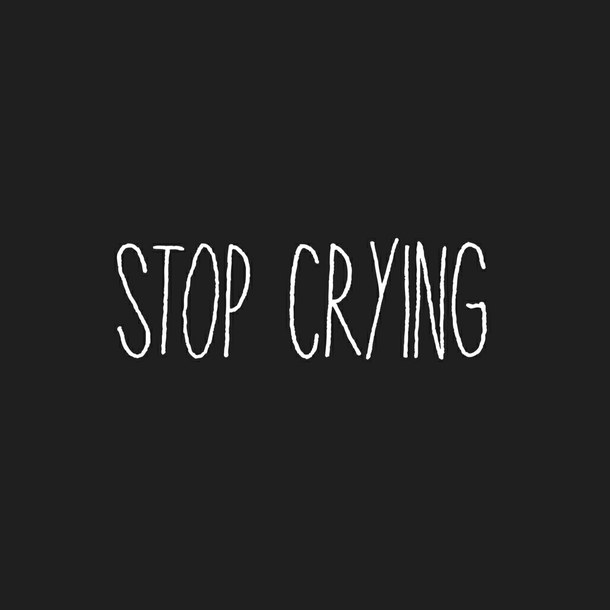

Her brother tried to intervene. “Stop crying,” he said. The oncologist also stepped into the uncomfortable situation: “Amanda, don’t be scared, please. We don’t know for sure [how bad your cancer is], so let us check first. OK?”

“Doctor will do the best for you,” continued her brother, “so don’t cry. OK?” The physician continued, almost a tag team now with the brother. “Today we can do the blood test. You don’t have to wait after doing that and can go home thereafter.”

“You have a lot of work, right?” she said, apologizing for letting her emotions take up so much of the doctor’s time. He tried to ease her mind. “No,” said the doctor, denying that he was too busy to address her concerns. But he immediately muddled his message. “I mean, you can do your blood tests today.”

A heartbreaking episode, heartbreaking in large part because of the awful situation poor Amanda was in, with so many things she could no longer do because of health problems and now with advanced cancer. Tragic, truly tragic. But compounding this tragedy was a veritable tragicomedy of miscommunication. Amanda breaks down crying and what message does she hear from her brother and doctor?

Stop crying.

Neither brother nor doctor acknowledged that, given her situation, she had a right to be scared, that it would in fact be abnormal not to be frightened. Neither realized that when people start crying, telling them to “stop crying” can actually make patients feel worse. I am sure I have made this same mistake scores of times in my own clinical practice. When a patient cries, our natural instinct as doctors, as humans, is to relieve their suffering, to say something that will stop their crying. It is perfectly normal, even compassionate, to reach out to soothe someone who is crying, to gently tell them not to cry, that everything will be okay.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

How to Make People Think Robots and Corpses Have Feelings

The right to die has played a critical role in the development of the doctor/patient relationship. It was families clamoring for the right to allow their loved ones to die who forced the world to recognize that physicians’ medical decisions aren’t just medical decisions, but involve enormous value judgments. In 1975, Karen Ann Quinlan’s loving parents asked her doctors to remove her ventilator, Quinlan having suffered irreversible brain damage that put her in a persistent vegetative state. Her doctors refused, saying such an action was medically inappropriate. The New Jersey Supreme Court, and the majority of the lay public, concluded that the doctors were exceeding their authority, in making moral judgments about whether Quinlan should live or die.

When I tell people Quinlan’s story (for example, in my book Critical Decisions), I present it as an example of the distinction between medical facts and value judgments. Physicians typically hold expertise about medical facts – about whether people like Quinlan in persistent vegetative state can experience pain or joy; about whether or not her ventilator was prolonging her life. But decisions about whether to keep Quinlan on the ventilator are value judgments, and physicians have no special expertise, or power, to make these decisions.

As it turns out, I’m partly wrong about the distinction between medical facts and value judgments. Recent research on, among other things, people’s attitudes towards robots has shown that sometimes medical judgments – whether, say, a person with persistent vegetative state can experience pain – are influenced by our moral thinking. Sometimes, when our moral sensibilities are offended, we attribute feelings and intentions to beings incapable of harboring such states of mind.

In one study, for example, the researchers described persistent vegetative state to participants. They explained that people in PVS have no conscious awareness – cannot experience pain or joy, and are unaware of their surroundings. They then asked participants to imagine that a nurse was purposely disconnecting a patient’s feeding tube at night, hoping the patient would die so the relatives would get their inheritance (and pass part of that inheritance to the nurse). Pretty evil, yes? I agree. And because of the evilness of this act, people began attributing feelings to the patient with PVS. When some humanoid thing is harmed, we recognize the immorality of those harms. Consequently, many of us begin attributing feelings and thoughts to the person or thing being harmed.

How do I know that it was the evilness of the act that caused people to believe that the patient with PVS could experience pain? Because another group of people were given the same scenario, but were told that the tube feedings were interrupted at night by accident, due to a technical error. This group of participants were significantly less likely to attribute states of mind to the patient.

Not convinced? (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Talking To Your Doctor About Out-Of-Pocket Costs Can Save You Money

Healthcare is often really costly. And with increasing frequency, a significant chunk of those costs is being passed on to patients in the form of high deductibles, copays, or other out-of-pocket expenses. As a result, millions of Americans struggle to pay medical bills each year.

What’s a poor patient to do?

For starters–they can talk to their doctors about these costs. According to a study my colleagues and I just published, when healthcare costs come up for discussion during clinical appointments, doctors and patients increasingly discuss strategies for how to lower out-of-pocket expenditures.

In the study, we analyzed transcripts of almost 2,000 outpatient clinical appointments, appointments audio recorded and transcribed by Verilogue Inc., a marketing research firm whose CEO, Jamison Barnett, was generous enough to collaborate with us on this research. (Full disclosure: All the doctors and patients gave permission to be audio recorded by the company. Verilogue removed all identifying information from the transcripts. And my colleagues and I did not enter into any financial relationship with the company, nor cede any control over our right to publish our findings.)

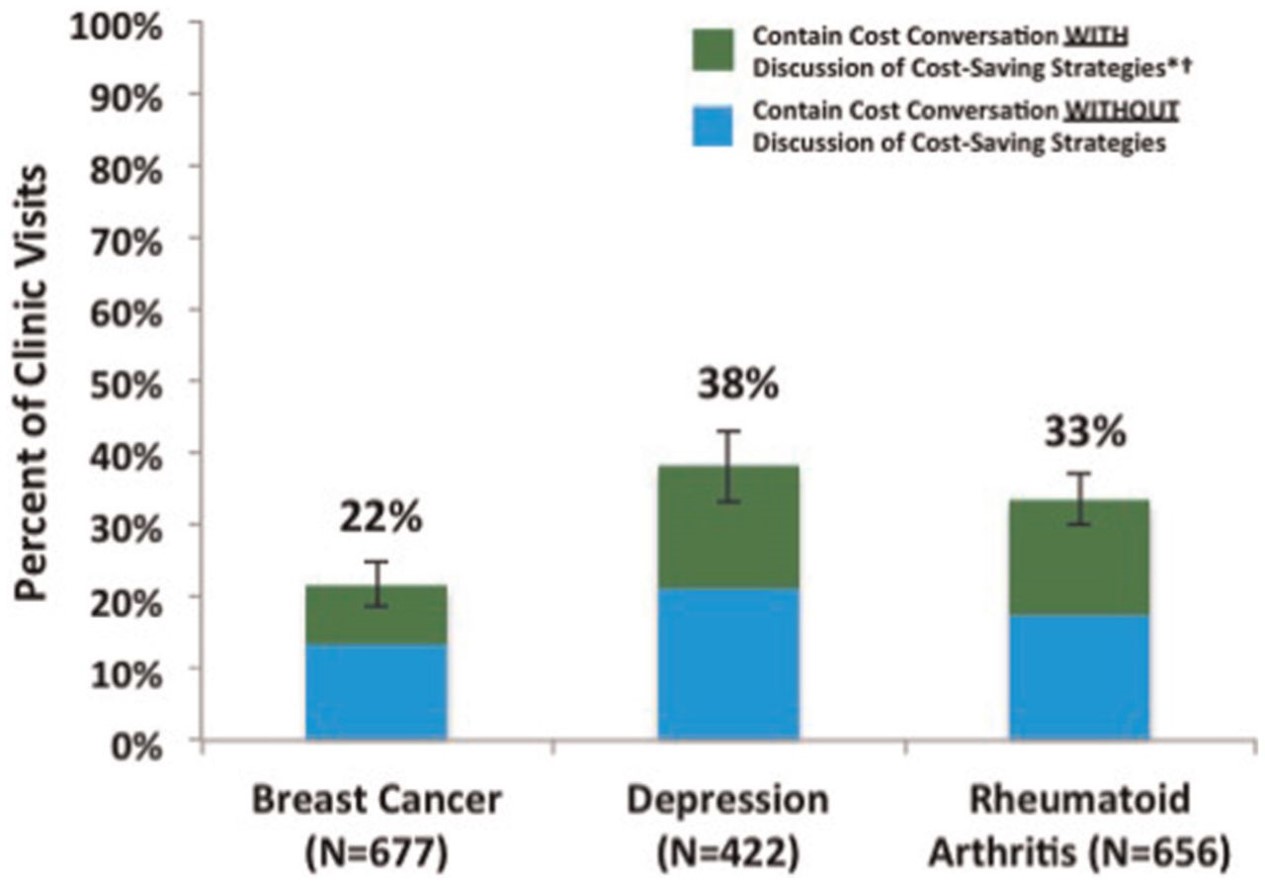

We analyzed three groups of patients, all of whom potentially face high out-of-pocket costs: breast cancer patients seeing their oncologists; rheumatoid arthritis patients seeing their rheumatologists; and patients with depression seeing their psychiatrists. We looked for any conversation that touched on the topic of healthcare costs–from discussions of whether insurance would “cover” a specific service (or whether the patient would instead be responsible for its cost) to patient complaints about out-of-pocket costs they’d already incurred from services ordered by their doctors during previous appointments.

In the first article published from these analyses (recently released on the website of Medical Decision Making), we focused on the strategies doctors and patients discuss to reduce patient out-of-pocket costs. And what did we find? That discussion of cost-reducing strategies was both common and rare. Common, in that once healthcare costs came up in the conversation, discussion of cost-reducing strategies occurred almost 40% of the time. Rare, in that healthcare costs came up as a topic of conversation in only 22-38% of the out-patient visits, meaning that in the majority of encounters, there was no discussion of healthcare costs, and thus no discussion of how to reduce patients’ out-of-pocket expenditures. Here is a picture showing those findings:

Sometimes doctors and patients found ways to reduce out-of-pocket costs without changing the plan of care. For example, doctors would refer patients to copay assistance programs, or give them free medication samples. Sometimes they would play around with the logistics of care, moving an expensive test up to December rather than January, so that the patient would not have to start spending through her deductible again.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Russell Wilson's Recovery Water: Miracle Cure or Magical Thinking?

Russell Wilson took a hard hit to the head in the NFC Championship game last year against the Green Bay Packers. His team, the Seattle Seahawks, won the game, but would Wilson, the team’s star quarterback, recover in time for the next game? That game, by the way, goes by the name The Super Bowl.

“The next day I was fine,” Wilson told Rolling Stone. “It was the water.”

Wilson was referring to a product called Reliant Recovery Water, a pseudoscientific concoction of “nano bubbles and electrolytes” that Wilson is convinced helps heal athletic injury. “I know it works,” he enthused to Rolling Stone. “Soon you’ll be able to order it straight from Amazon.”

If enough people buy the water, Wilson will become even richer than he already is, because he is an investor in the company. Some of you might think that Wilson is a quack, deceiving us for his own personal gain. But I expect that Wilson sincerely believes in the benefits of recovery water. Nevertheless as a wealthy and famous celebrity, he should either divest from the company or stop spouting off about the wonders of this bogus product. With fame comes responsibility, and Wilson’s endorsement is irresponsible and risks harming the people unlucky enough to believe his claims.

To understand how I’ve come to this conclusion, bear with me while I lay out some important distinctions.

First off, we need to distinguish between stupidity and ignorance. By no measure that I’m aware of could Russell Wilson be called a stupid man. He managed to graduate from college in 3 years, while playing both football and baseball at a division 1 school, North Carolina State, known for the rigor of its academics. And now he is one of the best quarterbacks in the NFL, quarterback being one of the most intellectually demanding positions in all of competitive sports. As a quarterback, Wilson has to quickly read opposing defenses, even as those defenses use elaborate methods to mask their intentions, and then even more quickly he has to react to the play as it unfolds, while avoided the bone-crushing efforts of the 300-pounders rushing in his direction. What I’m trying to say is – Russell Wilson is a very smart dude!

But Russell Wilson is also ignorant. He doesn’t know enough about medical science to judge the merits or demerits of Recovery Water. Ignorance is nothing to be embarrassed about. All of us are ignorant. I am completely ignorant about the history of Zimbabwe, know next to nothing about the difference between Merlot and Cabinet Sauvignon, can’t tell the difference between a nickelback and safety, and can’t describe the functioning of a carbonator to save my life. Ignorance is the dominant way of life for us human beings. Part of wisdom, however, is recognizing our own ignorance – knowing when to talk like experts and when to keep our opinions to ourselves.

Which raises a second distinction – between Russell Wilson’s watery pronouncements and Dr. Mehmet Oz’s many enthusiastic product endorsements. Oz has justifiably received extensive criticism in recent months, for making unsubstantiated claims about many products he discusses on his popular television show. Unlike Wilson, however, Oz ought to know better than to make these claims. You see, Oz isn’t ignorant about medical science. Instead, he is an accomplished physician on the medical faculty of an Ivy League school. But in an effort to, I don’t know, get higher ratings or find new things to talk about on his show (how often can you tell people: “Eat less and exercise more!”), or to sell products he has a financial stake in, Oz keeps spouting what he has to know to be nonsense. Oz is not ignorant when making these claims. He’s calculatedly misleading his viewers. He deserves none of our respect.

By contrast, Russell Wilson probably believes wholeheartedly in the wonders of his nano bubbly beverage. He is not a quack, like Oz. Instead he’s just a smart celebrity who got himself involved in something he doesn’t understand.

Which brings me to my final distinction – between celebrity endorsements and paid celebrity endorsements. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

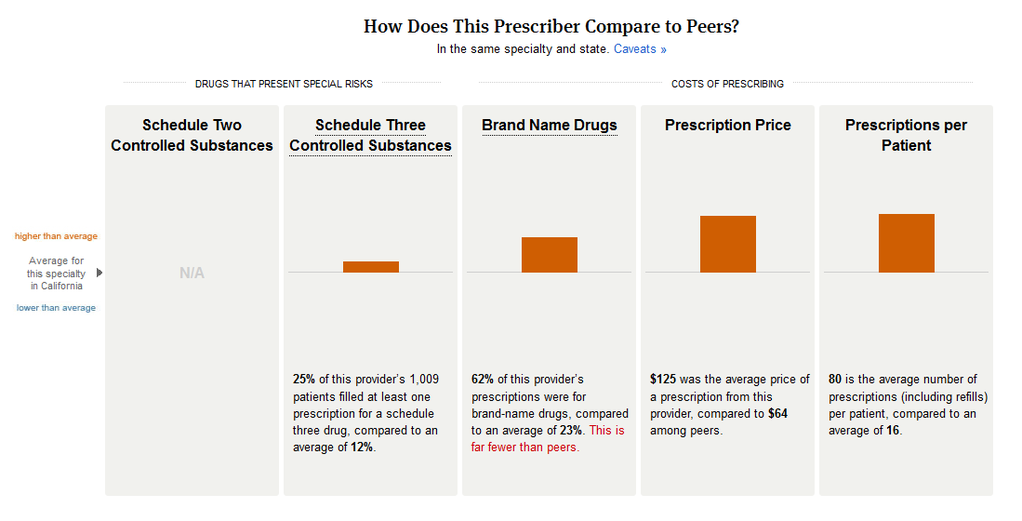

Would This Picture Help You Shop for a Doctor?

Has Mammography Created an Epidemic of Pseudo-Survivorship?

Karen Vogt’s breast cancer journey began like many others, with her breasts painfully squeezed into a mammography machine. At age 52, it was far from her first mammogram, but this scan would be the most consequential by far. It revealed microcalcifications, little areas of breast tissue speckled with deposits of calcium that her radiologist worried were suspicious for a nascent cancer, especially since these specks hadn’t been so conspicuous twelve months earlier. A biopsy proved that the radiologist’s suspicions were warranted. Vogt had a small cancer in her left breast, a ductal carcinoma in situ, as her doctors called it. Stage 0 cancer. What should she do?

This week, medical researchers published a study showing that when women are diagnosed with stage 0 breast cancer, no matter what treatment they receive, their life expectancy is equivalent to women who were never diagnosed with breast cancer. This finding further fuels debates about whether we are screening for and/or treating breast cancer too aggressively. Last year, in fact, a study came out suggesting that even in women 50 years of age and older, annual mammographies are not the life-savers that they were made out to be by medical experts. According to these studies, for every woman like Vogt with a cancer detected by mammography, hundreds more will go through the painful test without any cancer being detected and dozens will experience the harms of “false positive” test results, a term medical experts use to refer to abnormal findings which do not turn out to be a cancer. And just this week, a study was published showing that stage 0 breast cancers are better off untreated

Yet despite increasing evidence of the significant harms of mammography, compared to its relatively modest benefits, many American women dutifully continue to receive annual tests. Why do they remain enthusiastic about mammography? In large part because many women who were harmed by mammography believe the opposite. By identifying non-invasive lesions, like the DCIS discovered in Karen Vogt, mammography has created a community of women incorrectly convinced that the test saved their lives.

Has overuse of mammography created a false epidemic of breast cancer “survivorship?” (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)