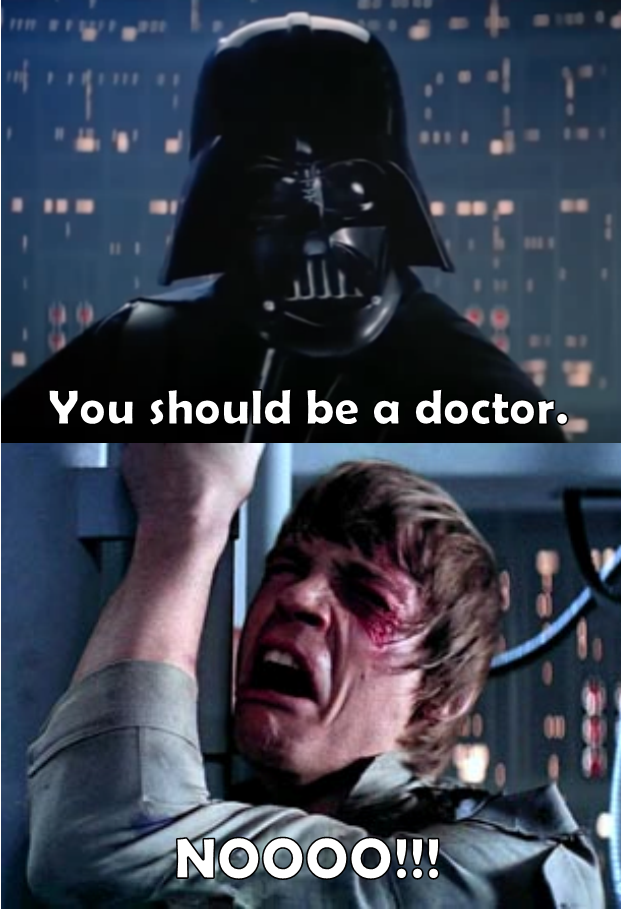

I recently spoke with a reporter about a new effort, by Medicare, to persuade dialysis centers to care for a wider range of primary care health needs for people with kidney failure. I’ll give you a teaser for that article below, but first want to point out what struck me as the most notable part of the article – the reporter referred to me as a health economist! My father has always been disappointed in me, for not practicing medicine full-time, and for pursuing soft social sciences like psychology. Maybe he will be happy to find out that someone thinks of me as an economist.

I recently spoke with a reporter about a new effort, by Medicare, to persuade dialysis centers to care for a wider range of primary care health needs for people with kidney failure. I’ll give you a teaser for that article below, but first want to point out what struck me as the most notable part of the article – the reporter referred to me as a health economist! My father has always been disappointed in me, for not practicing medicine full-time, and for pursuing soft social sciences like psychology. Maybe he will be happy to find out that someone thinks of me as an economist.

Now here’s that news report:

The CMS announced on Wednesday the first suite of accountable care organization models specifically geared toward treatment of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). More than 600,000 people in the U.S. live with the condition, which requires patients to undergo costly, but life-sustaining dialysis treatments each week that account for nearly 6% of Medicare spending.

The 13 ESRD seamless care organizations, called ESCOs, began to share this month the financial risks for treating Medicare beneficiaries with kidney failure in 11 U.S. states. The models are meant to encourage dialysis providers to “think beyond their traditional roles” and provide patient-centered care, the CMS announcement said.

DaVita and Fresenius, the nation’s two largest dialysis providers, both won bids to participate. DaVita HealthCare Partners will have three ESCOs located in Phoenix, Miami and Philadelphia. Fresenius Medical Care will have six, located in San Diego, Chicago, Charlotte, N.C., Philadelphia, Columbia (S.C.) and Dallas. Both providers expressed enthusiasm for participation in the program, and agree it is a step in the right direction. Still, both providers also expressed reservations.

“Deciding whether or not to participate has been a huge challenge,” said Robert Sepucha, senior vice president of corporate affairs for Fresenius. Some of the measurements are not barometers of good quality care specifically for dialysis providers, he said, and the economic incentives “are not perfect.” He added, “There are flaws that could prevent it from becoming the large-scale, new payment system a lot of us have hoped for.”

The CMS began taking applications for the ESCO initiative in April 2014, but the plan drew early criticism. Kidney providers supported the concept, but questioned the application process and the metrics selected. Some thought the models should expand to target patients in earlier stages of the disease to slow its progression and subsequent costs.

“If you’re not doing good upstream management of the patient, you’re not going to be able to address the health needs and costs that could be avoided,” said Todd Ezrine, general manager for VillageHealth, the DaVita program that will host that organization’s ESCO.

He also said DaVita “scoured the country” to find markets where the shared saving program would be successful. CMS’ benchmarking standards would be difficult to reach in markets where DaVita already achieves good outcomes, as participants may not understand the level of additional improvement needed to avoid penalties, he said.

Over the past year, the two providers have not necessarily seen eye-to-eye on the kidney care metrics used by federal programs.

For example, for the second time in nearly two years, DaVita beat its competitor on a five-star rating system posted publicly on the Dialysis Facility Compare website. Of 586 top performers in the five-star category, DaVita owned 202 facilities, while Fresenius owned only 110, according to data released Thursday. Alternatively, Fresenius had 279 facilities of the 575 that appeared in the one-star category, compared with DaVita, which had only 38.

Though kidney providers originally seemed united in their skittishness about that program, DaVita made a pivot following the first round of results. Fresenius, on the other hand, continues to express hesitation.

Fresenius made changes to the way data are collected, and to its clinical programs, but that will change nothing because of the forced bell curve the CMS uses on the five-star rating system, Sepucha said. “As one clinic moves up, another clinic has to move down,” he said. “You could get rid of all one- and two-star clinics today, and tomorrow there would be a whole new set.”

The CMS star ratings are consumer-facing initiatives that focus on quality of care inside medical facilities. The ESCOs are alternative payment models designed to encourage dialysis providers to take responsibility for the quality and cost of care for a population of patients. It includes the patient’s total care, like managing other comorbidities and multiple medications, and is not just limited to care inside of dialysis facilities

It remains to be seen if concerns about the metrics specific to dialysis care will create disparities in the ESCO programs as well. The other two organizations participating include Dialysis Clinic, which will have programs in Newark, N.J., Spartanburg, S.C., and Nashville; and the Rogosin Institute, with an ESCO in New York.

In the meantime, health economists say providers can expect more bundling. Programs like ESCO are a reflection of a national focus on encouraging health providers from all specialties to put the patient first.

“Shouldn’t the person taking care of a patient already be doing everything they could? Of course,” said health economist, Dr. Peter Ubel, of Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. But bundled-payment models with shared financial risks do help reduce the tendency of for-profit industries to pay attention only to those products and services for which they get the biggest payments, he said.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Modern Healthcare.)