Irena Bucci was receiving follow-up care after delivering her second baby when the obstetrician discovered a problem with her kidneys. “My creatinine was rising,” creatinine being a waste product normally cleared out of the bloodstream by healthy kidneys, “and my doctor didn’t know why. I didn’t have high blood pressure or diabetes,” two diseases that are common causes of kidney failure. Bucci met with a number of kidney specialists, in hopes of uncovering the cause of her kidney failure. “But the tests didn’t discover one. And without a diagnosis, they couldn’t figure out how to treat my illness. They told me it was just a matter of time before my kidneys failed.”

In the absence of a transplant, kidney failure is usually treated by dialysis. With this treatment, patients no longer face imminent death. Prior to the emergence of dialysis, people with irreversible kidney failure usually died in a matter of weeks. On dialysis, many patients live for years. But they do not necessarily live in great health. The medical literature estimates that patients on dialysis face annual mortality rates close to 20%. Bucci desperately wanted to avoid that fate. “My doctor urged me to find a living donor, and get transplanted before I needed dialysis. A few even told me that since I am from Russia, I should go abroad and find someone willing to ‘donate’ a kidney.”

But Bucci was not comfortable receiving a kidney from a stranger—that struck her as both unethical and as medically dangerous: “Who knows what kind of organ you would get that way.” She also didn’t have any relatives who could serve as living donors. So she settled in for the long wait to receive a transplant from a deceased donor. At Georgetown University Medical Center, near where she lived, less than a quarter of their kidney transplant candidates receive a transplant in a typical year. Bucci knew that each one of those years she spent waiting for a transplant could be her last.

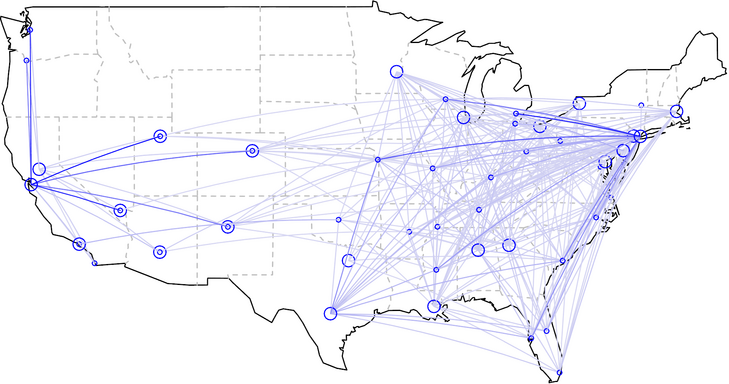

And then she read Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, and learned that he had flown to Tennessee to receive a liver transplant, and thought to herself: “Why don’t I do something like that!” She decided to get herself listed at as many transplant centers as possible, and travel to which ever one could find her a suitable organ.

Bucci began undergoing transplant evaluations at hospitals located relatively close to Washington D.C., but that operated in different transplant areas than Georgetown. In the process of undergoing those evaluations, she received some bad news that made it even more important for her to get listed at multiple centers – she had a PRA of 90. The PRA, or Panel Reactive Antibody test, estimates the percent of potential donor kidneys that a person’s immune system will reject. Probably as a result of her pregnancies, Bucci’s immune system was highly reactive; her body was choosy about what kind of foreign antigens it would tolerate. Whatever the reason for her high PRA, Bucci would be unable to accept 90% of eligible donors. As an IT expert with a Master’s degree in mathematics, it was not difficult for Bucci to figure out that her long wait for a kidney had just gotten longer.

That’s when Bucci began spending her free time getting herself onto as many transplant waitlists as possible. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)