Recently, I wrote an Op-Ed in the New York Timescalling upon physicians to discuss out-of-pocket costs with their patients before making medical decisions, and urging patients to take matters into their own hands if their physicians fail to initiate such conversations. This Op-Ed closely mirrored an argument I made in the New England Journal of Medicine with my colleagues Yousuf Zafar and Amy Abernethy, in which we equated out-of-pocket costs with treatment side effects. Since publishing these two articles, I have received a lot of positive feedback not only from laypeople, but also from healthcare providers. But I’ve also received a significant amount of pushback, some of it downright nasty. I want to touch upon some of this criticism, to more fully flesh out my thoughts on this controversial topic.

Recently, I wrote an Op-Ed in the New York Timescalling upon physicians to discuss out-of-pocket costs with their patients before making medical decisions, and urging patients to take matters into their own hands if their physicians fail to initiate such conversations. This Op-Ed closely mirrored an argument I made in the New England Journal of Medicine with my colleagues Yousuf Zafar and Amy Abernethy, in which we equated out-of-pocket costs with treatment side effects. Since publishing these two articles, I have received a lot of positive feedback not only from laypeople, but also from healthcare providers. But I’ve also received a significant amount of pushback, some of it downright nasty. I want to touch upon some of this criticism, to more fully flesh out my thoughts on this controversial topic.

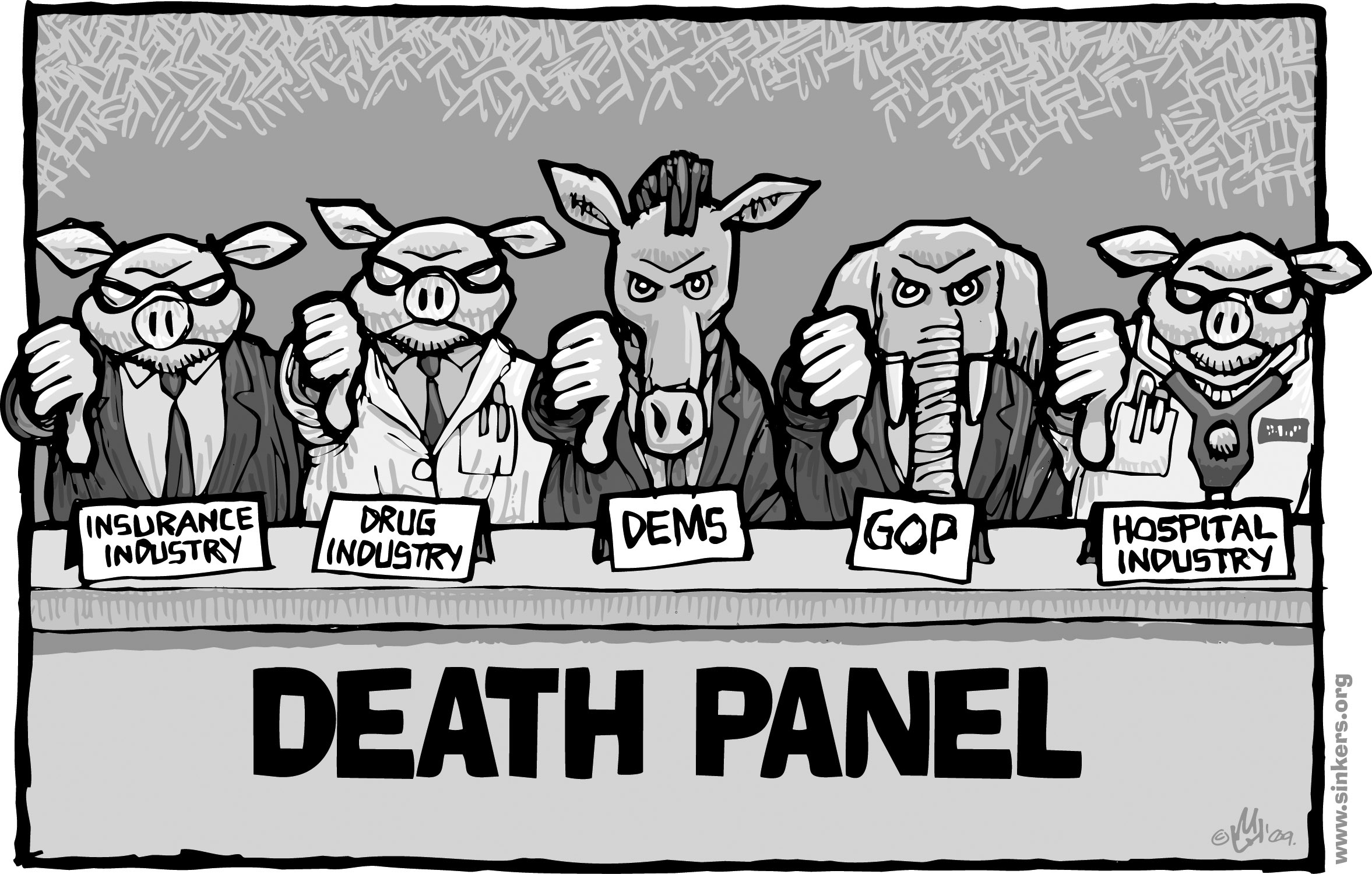

The controversy starts with concerns people have about letting the cost of medical care influence medical decisions. This concern was nicely summarized by one physician, who sent me an email stating: “I’m sure if, God forbid, you or a family member is ever seriously ill, you would want to try ANY potential curative or helpful treatment, regardless of price.” This physician then went on to claim that if either Zeke Emanuel or myself were to get sick, we would somehow find a way to get the best possible medical care regardless of price. Emanuel is a physician at Penn, and brother of former White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel, who helped write the Obamacare legislation. Emanuel was also at the center of the death panel controversy, with Obamacare criticsaccusing him of wanting to withhold care from elderly and disabled people. This physician seemed to be equating the topic of discussing healthcare costs with the idea of healthcare rationing, perhaps even thinking that holding such conversations is tantamount to a death panel… (Read more and view comments at Forbes)

What's Fair About Price Discrimination in Pharmaceutical Markets

A while back, DVD companies hoping to sell their products in countries like Poland faced a dilemma. They could sell their products at a nice profit in the booming U.S. market, but to sell products in those other countries, they had to lower their prices. Such variable pricing is a common business practice. All kinds of services are less expensive in Poland than in the United States. An hour with a psychotherapist or personal trainer, for instance, is significantly cheaper in Warsaw than in New York City. But small, non-perishable products like DVDs create big problems for manufacturers. If the going price of such a product is significantly lower in Poland than the U.S., savvy business people will purchase large numbers of DVDs in Poland and ship them back to the United States to sell them for a hefty profit. They can’t do the same with personal trainers or psychotherapists, to the chagrin, no doubt, of some people in those professions.

A while back, DVD companies hoping to sell their products in countries like Poland faced a dilemma. They could sell their products at a nice profit in the booming U.S. market, but to sell products in those other countries, they had to lower their prices. Such variable pricing is a common business practice. All kinds of services are less expensive in Poland than in the United States. An hour with a psychotherapist or personal trainer, for instance, is significantly cheaper in Warsaw than in New York City. But small, non-perishable products like DVDs create big problems for manufacturers. If the going price of such a product is significantly lower in Poland than the U.S., savvy business people will purchase large numbers of DVDs in Poland and ship them back to the United States to sell them for a hefty profit. They can’t do the same with personal trainers or psychotherapists, to the chagrin, no doubt, of some people in those professions.

When some people found out about this arrangement, they were creeped out. It seemed like the companies were up to their slimy old tricks. How dare they doctor a DVD so that an honest consumer can’t play it on his or her DVD machine? It felt like the DVD manufacturers were getting greedy. If they were willing to sell DVDs at that price in Poland, after all, then clearly such lower prices must still be profitable. Why wouldn’t they sell DVDs at that same price in the United States? …(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

On the Allure of Cheating

Recently, my 15-year-old son and a group of his friends went out together for dinner and a movie. The movie they chose to see was an R-rated comedy, a fact that only struck them when they approached the ticket office and realized they would not be allowed to see the movie. Not to be deterred, they did what has almost become a rite of passage for 15-year-olds – they bought tickets to another movie, and then snuck in to the R-rated one.

Recently, my 15-year-old son and a group of his friends went out together for dinner and a movie. The movie they chose to see was an R-rated comedy, a fact that only struck them when they approached the ticket office and realized they would not be allowed to see the movie. Not to be deterred, they did what has almost become a rite of passage for 15-year-olds – they bought tickets to another movie, and then snuck in to the R-rated one.

But their adventure was not over yet. They quickly caught wind of a rumor that another group of underage kids had just been kicked out of the same movie. As they approached the doorway to the theater showing the forbidden movie, they saw two theater employees walking down the hallway. Someone on to their scam? They quickly walked the other way, peeking back for a window of opportunity to slip into the theater unnoticed. Hearts racing, the fear centers of the brain on high alert, they dashed into the theater when the employees looked the other way, and scrambled into a row of seats before they could be detected… (Read more and view comments at Psychology Today)

A Magician's Eye for Consumer Scams

One of the themes running through Fooling Houdini that I like the most was the strong connection that Stone made between magic, con artistry, and even common business practices. Magicians have long been known for their ability to spot scams. After all, their profession is based on developing the ability to fool people. That is why Houdini, himself, spent much of the end of his career trying to debunk con artists. But as someone who teaches behavioral economics to business students, and in the process spends lots of time debating the ethics of exploiting consumer weakness, it was refreshing to see this passage from Stone’s book:

One of the themes running through Fooling Houdini that I like the most was the strong connection that Stone made between magic, con artistry, and even common business practices. Magicians have long been known for their ability to spot scams. After all, their profession is based on developing the ability to fool people. That is why Houdini, himself, spent much of the end of his career trying to debunk con artists. But as someone who teaches behavioral economics to business students, and in the process spends lots of time debating the ethics of exploiting consumer weakness, it was refreshing to see this passage from Stone’s book:

“Everywhere I looked, I saw rip-offs. Why do car rental agencies urge you to buy optional insurance when in most cases your own insurance, or credit card, covers any damage? Why does jock itch cream cost more than athlete’s foot medication, even though they’re the same thing? Is it because companies know they can charge a premium for a more embarrassing product? Why do Americans spend $8 billion each year on bottled water, when the two top-selling brands (Aquafina and Dasani) come from municipal sources? Why do so many investors buy mutual funds when most funds underperform the markets they’re supposed to one-up? (There are more funds than stocks. Think about that for a moment.)”

“Cruising down Interstate 15, I came upon a sign that read SPEED LIMIT 70 MPH ENFORCED BY AIRCRAFT and wondered if that, too, was a scam .”

Hard not to be a skeptic once you understand how easy it is to dupe people.

Can Comics Improve Medical Care?

Take a look at this wonderful video where a physician and a nurse explain how comic books, what they called “graphic medicine”, can improve medical care.

You might also want to check out the website of the graphic medicine collaborative they have pulled together.

(Click here to view comments)

Stephen Hawking on Aid in Dying

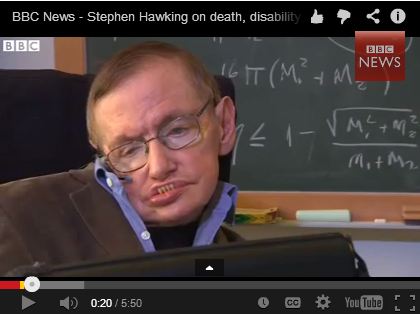

World-famous physicist, Stephen Hawking, is now advocating in favor of physician-assisted death, in the video shown here. I am both very glad that he is still alive, so many years after developing his illness, and that he is advocating for those people who circumstances and suffering leads them to request assistance in ending their lives. These are never easy issues, as the back and forth over my recent blog posts on this topic have shown. But not everybody with ALS can draw upon the intellectual, emotional and financial resources that have helped Stephen Hawking live so long with this condition.

World-famous physicist, Stephen Hawking, is now advocating in favor of physician-assisted death, in the video shown here. I am both very glad that he is still alive, so many years after developing his illness, and that he is advocating for those people who circumstances and suffering leads them to request assistance in ending their lives. These are never easy issues, as the back and forth over my recent blog posts on this topic have shown. But not everybody with ALS can draw upon the intellectual, emotional and financial resources that have helped Stephen Hawking live so long with this condition.

(Click here to view comments)

Congratulations to the MacLean Center

The University of Chicago Medicine’s MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, where I trained in the early 90s, has been awarded the prestigious Cornerstone Award from the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities for “outstanding contributions from an institution that has helped shape the direction of the fields of bioethics and/or medical humanities.” To learn more about the award, read here.

The University of Chicago Medicine’s MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, where I trained in the early 90s, has been awarded the prestigious Cornerstone Award from the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities for “outstanding contributions from an institution that has helped shape the direction of the fields of bioethics and/or medical humanities.” To learn more about the award, read here.

Is There a Difference Between Suicide and Ending One's Life?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines suicide as: “Death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior .” The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it as: “the act or an instance of taking one’s own life voluntarily and intentionally especially by a person of years of discretion and of sound mind.” By both of those definitions, the act of a terminally ill person ingesting an overdose of pills with the intention of ending their life would qualify as suicide.

To that extent, Kathryn Tucker, in her response to my earlier post, was wrong to characterize my use of the term “physician assisted suicide” as being “inaccurate.”

Instead of the word “assisted,” she prefers the word “aid.” But logically and technically, I cannot see a difference between “physician assisted suicide” and “physician aid in dying.” Nor do I see a moral difference. As I pointed out in my post, I have been a long time supporter of people’s rights to end their lives when they are suffering from terminal illnesses, and of the appropriateness of physicians helping them do this.

But Tucker made some outstanding points in her essay, ones I am very grateful to have learned from, and ones that are very much in the spirit of my original post. She points out that the way people perceive words matters, separate from the specific definition of those words. She points out that the word “suicide” is stigmatized. Many, perhaps most, acts of suicide are the acts of people who are not in their right state of mind. Most of us physicians are trained, correctly, to see suicide as a warning that a patient needs help, and to treat suicide as something to prevent rather than assist in.

I cannot dispute when a terminally ill person says that describing them as suicidal is “disrespectful and hurtful.” But I can tell you this. I did not use the word suicide with any intention to be disrespectful or hurtful. The goal of my essay was to point out that it’s a mistake to equate a person ending their own life with the concept of dignity. It can also be dignified not to end one’s life. It can be dignified to fight all the way to the end, with the most aggressive possible care. It can be dignified to enroll in hospice care, and die naturally without taking any substances that hasten one’s end. And yes, it can be dignified for a terminally ill person to take control over their own destiny, and ingest medications that end their life.

Thanks to Kathryn Tucker, I will not use the phrase physician-assisted suicide again, except to make sure people understand that the phrase carries connotations that are unnecessarily pejorative.

A Debate on Death with Dignity

The below post is a response to my article Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide by Kathryn L. Tucker, JD. My own thoughts on her response are here.

The below post is a response to my article Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide by Kathryn L. Tucker, JD. My own thoughts on her response are here.

In a Forbes.com oped, “Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide, Duke University physician Peter Ubel writes: “I think it is wrong-headed to equate assisted suicide with the concept of a dignified death.”

Dr. Ubel’s use of the inaccurate, value-laden term “assisted suicide” to describe a terminally ill patient’s choice to shorten a dying process that the patient finds unbearable – as some journalists also wrongly do – is concerning. Words matter.

Medical, health policy and mental health professionals recognize that the term “assisted suicide” is inaccurate, biased and pejorative in this context. Increasingly, these organizations have adopted the more accurate and neutral term “aid in dying” to refer to this choice.

The nation’s largest public health association, theAmerican Public Health Association, adopted a policy supporting aid in dying, recognizing that: “the term ‘suicide’ or ‘assisted suicide’ is inappropriate when discussing the choice of a mentally competent terminally ill patient to seek medications that he or she could consume to bring about a peaceful and dignified death.” The policy emphasizes: “the importance to public health of using accurate language.” The American Medical Women’s Association has adopted similar policy, as have a number of other national medical organizations.

A growing number of states, including Oregon, Washington, Montana,Vermont and Hawaii, permit mentally competent, terminally ill patients to obtain medications they can ingest to bring about a peaceful death if their suffering becomes unbearable. The Oregon, Washington, and Vermont lawsclearly state: “Actions taken in accordance with [the Act] shall not, for any purpose, constitute suicide, assisted suicide, mercy killing or homicide, under the law.”

Terminally ill patients do not want to die but are facing an imminent death, most after long efforts to cure their illness and heroic efforts to palliate symptoms. Despite excellent pain and symptom management, some find the dying process unbearable and want to achieve a peaceful death. Patients who can choose aid in dying do not consider that they are committing “suicide,” and find the suggestion that they are deeply offensive, stigmatizing and inaccurate. Many have publicly expressed that the term is hurtful and derogatory to them and their loved ones.

“All I am asking for is to have some choice over how I die,” wrote terminally ill patient Louise Schaefer in a letter to The Sacramento Bee. “Portraying me as suicidal is disrespectful and hurtful to me and my loved ones. It adds insult to injury by dismissing all that I have already endured; the failed attempts for a cure, the progressive decline of my physical state and the anguish which has involved exhaustive reflection and contemplation leading me to this very personal and intimate decision about my own life and how I would like it to end.”

Dying patients who choose aid in dying want to live, as evidenced by the fact that more than one-third of these terminally ill patients don’t ingest the medication even after they obtain it. But they derive great comfort knowing they have that option. For those who do take the medication to achieve a peaceful death, they have been able to cross the threshold to death in a manner consistent with their values and beliefs, and consider this choice to have enabled them to exercise a final act of autonomy consistent with how they have lived their whole life.

As noted philosopher and law professor Ronald Dworkin observed in his book Life’s Dominion (Knopf 1993): “…we live our whole lives in the shadow of death…we die in the shadow of our whole lives….We worry about the effect of life’s last stage on the character of life as a whole, as we might worry about the effect of a play’s last scene or a poem’s last stanza on the entire creative work.” We ought not insult and diminish this choice by applying an inaccurate, pejorative term. Words matter.

Kathryn L. Tucker, JD, is the Director of Advocacy & Legal Affairs for the nation’s leading end-of-life advocacy, education and support organization, and teaches Law, Medicine and Ethics at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.Compassion & Choices

Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide

In 2008, the state legislature of Washington passed what was called the Death with Dignity Act, a law that legalized physician assisted suicide. Under the law, terminally ill patients (predicted to have less than six months to live) can request prescriptions for lethal medications from their physicians, under a series of safeguards: multiple requests for example, determination of competency, and the like. Then, if the patients so choose, they can ingest the pills at the time of their choosing, thus controlling the manner and location of their demise, a last act of control in the face of an otherwise debilitating illness.

In 2008, the state legislature of Washington passed what was called the Death with Dignity Act, a law that legalized physician assisted suicide. Under the law, terminally ill patients (predicted to have less than six months to live) can request prescriptions for lethal medications from their physicians, under a series of safeguards: multiple requests for example, determination of competency, and the like. Then, if the patients so choose, they can ingest the pills at the time of their choosing, thus controlling the manner and location of their demise, a last act of control in the face of an otherwise debilitating illness.

I have no beef with the letter or spirit of Washington’s law. I have long contended that in rare circumstances, physician assisted suicide is a compassionate and morally appropriate policy. Nor am I worried about the way the Washington law has worked in practice. Indeed, a New England Journal of Medicine study from April demonstrates that patients have chosen assisted suicide sparingly, and without undue coercion from clinicians urging them to “off themselves”.

My beef is not with the letter of the Washington law, it’s with the name. I think it is wrong-headed to equate assisted suicide with the concept of a dignified death. Such a link unduly narrows the concept of dignity, and potentially undermines our ability as clinicians to help patients find other ways of achieving a dignified death… (Read more and view comments at Forbes)