I could go on quoting Abraham Lincoln all day long, for he was one of the finest writers of his or any time. Here’s one very special quote, where Lincoln uses the metaphor of a snake to make distinctions between slavery itself being bad, versus policies to limit slavery to the south, versus policies to prevent slavery from expanding into new US territories.

I could go on quoting Abraham Lincoln all day long, for he was one of the finest writers of his or any time. Here’s one very special quote, where Lincoln uses the metaphor of a snake to make distinctions between slavery itself being bad, versus policies to limit slavery to the south, versus policies to prevent slavery from expanding into new US territories.

If I saw a venomous snake crawling in the road, any man would say I may seize the nearest stick and kill it. But if I found that snake in bed with my children that would be another question. I might hurt the children more than the snake, and it might bite them.

In other words, slavery is bad, but ending slavery in the South might harm unintended victims.

Much more, if I found it in bed with my neighbor’s children, and I had found myself by a solemn oath not to meddle with his children under any circumstances, it would become me to let that particular mode of getting rid of the gentleman alone.

In other words, once they signed on to the Constitution, Northerners became duty-bound to leave slavery alone in the south.

But if there was a bed newly made up, to which the children were to be taken, and it was proposed to take a batch of young snakes and put them there with them, I take it no man would say there was any question how I ought to decide.

And that is the reasoning by which Lincoln concluded that slavery should not be expanded into new territories, a position the south could not tolerate, because Southerners saw such a policy as the beginning of the end of slavery in their lands. What a brilliant way to frame the argument.

(Click here to view comments)

In an eye opening article on Aborigines, Michael Finkel paints a colorful picture of the local landscape:

In an eye opening article on Aborigines, Michael Finkel paints a colorful picture of the local landscape:

In the

In the  “Few sinners are saved after the first twenty minutes of a sermon.”

“Few sinners are saved after the first twenty minutes of a sermon.” I could go on quoting Abraham Lincoln all day long, for he was one of the finest writers of his or any time. Here’s one very special quote, where Lincoln uses the metaphor of a snake to make distinctions between slavery itself being bad, versus policies to limit slavery to the south, versus policies to prevent slavery from expanding into new US territories.

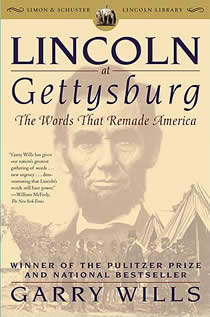

I could go on quoting Abraham Lincoln all day long, for he was one of the finest writers of his or any time. Here’s one very special quote, where Lincoln uses the metaphor of a snake to make distinctions between slavery itself being bad, versus policies to limit slavery to the south, versus policies to prevent slavery from expanding into new US territories. For at least the last few decades, conservative legal scholarship in United States has paid a great deal of attention to the idea of original intent. According to this view, the best way to interpret the Constitution of the United States is to imagine what the writers of that document meant at the time they wrote it, and to make sure that modern interpretations do not stray any further than necessary from this meaning.

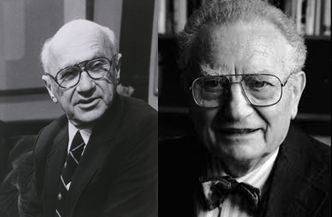

For at least the last few decades, conservative legal scholarship in United States has paid a great deal of attention to the idea of original intent. According to this view, the best way to interpret the Constitution of the United States is to imagine what the writers of that document meant at the time they wrote it, and to make sure that modern interpretations do not stray any further than necessary from this meaning. In their book Animal Spirits, George Akerlof and Robert Shiller recount the intellectual battles waged between Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson, two of the 20th century’s most important economists. Friedman was a huge believer in the power of markets, and in consumers’abilities to make rational decisions. Samuelson also recognized the power of markets, but thought Friedman went too far. Akerlof and Shiller say that Samuelson described Friedman as:

In their book Animal Spirits, George Akerlof and Robert Shiller recount the intellectual battles waged between Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson, two of the 20th century’s most important economists. Friedman was a huge believer in the power of markets, and in consumers’abilities to make rational decisions. Samuelson also recognized the power of markets, but thought Friedman went too far. Akerlof and Shiller say that Samuelson described Friedman as: Here’s the opening paragraph from a New York Times magazine article published in May of this year, about monk seals. What a great way to open the piece:

Here’s the opening paragraph from a New York Times magazine article published in May of this year, about monk seals. What a great way to open the piece: During a particularly miserable World War II battle, a military analyst estimated that it cost $25,000 in artillery shells for each enemy soldier killed. That caused one soldier to ask: “Why wouldn’t it be better to just offer the Germans $25,000 to surrender?”

During a particularly miserable World War II battle, a military analyst estimated that it cost $25,000 in artillery shells for each enemy soldier killed. That caused one soldier to ask: “Why wouldn’t it be better to just offer the Germans $25,000 to surrender?”