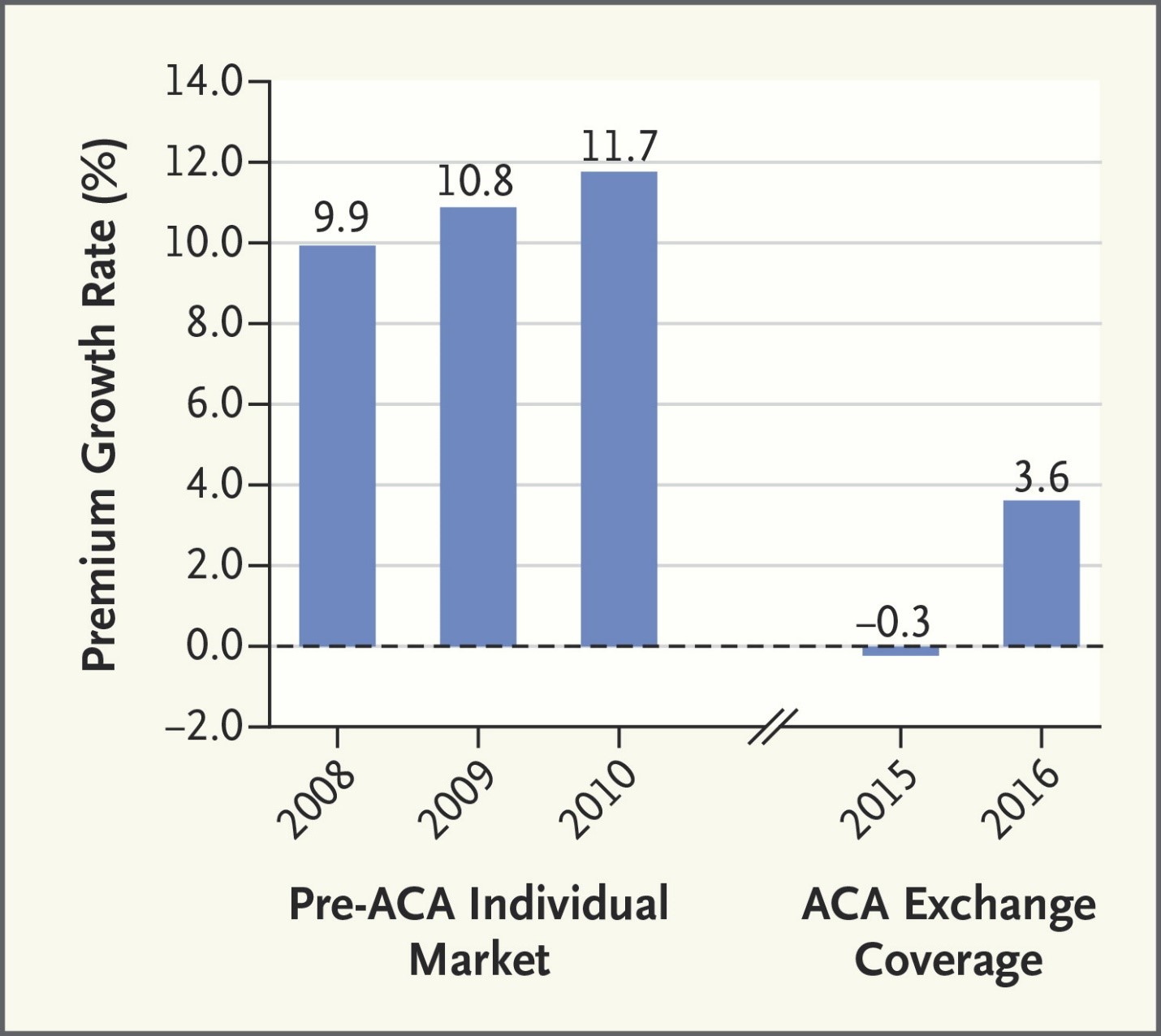

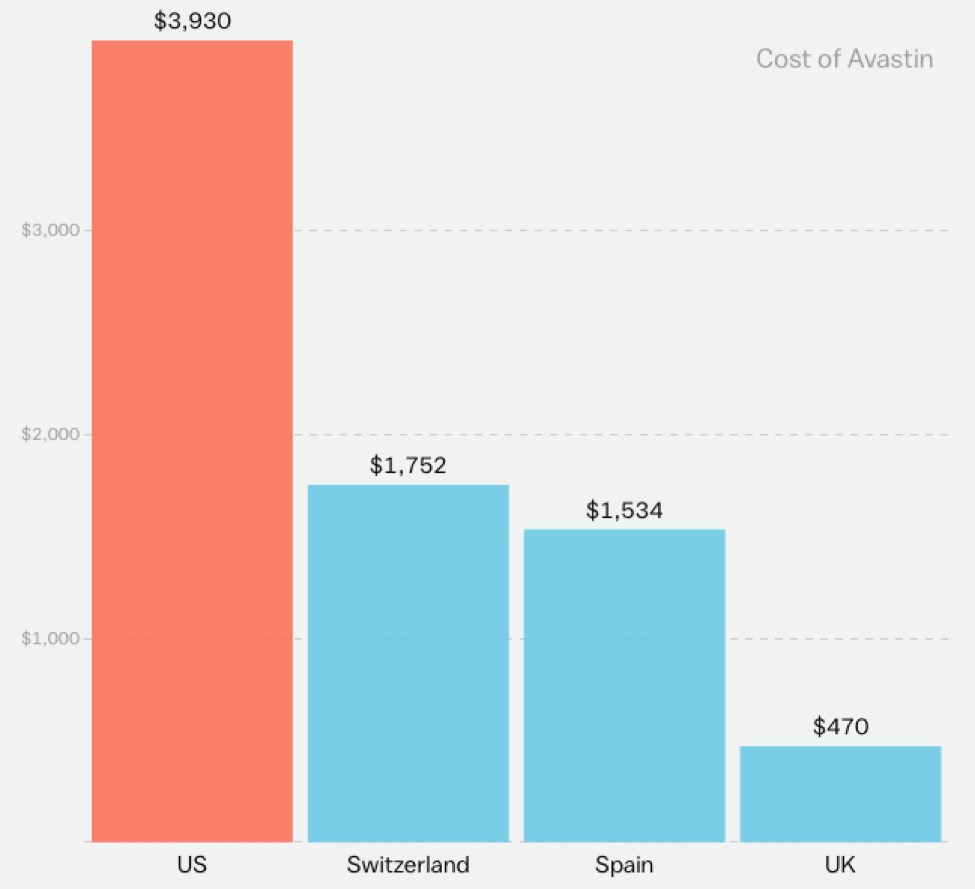

In a recent post, I showed two drugs that were much more expensive in the United States than elsewhere. One was for rheumatoid arthritis and the other for hepatitis C. Today we get to look at a cancer drug, Avastin, and just how much more Americans pay for it than people in other countries.

This is not acceptable.

The USA Is Number One… In Healthcare Prices!

The folks at Vox media put together a series of pictures, illustrating how much more expensive medical care is in United States compared to other developed countries. Today, and in the next few days, I’m going to circulate some of those pictures. Prepare yourself for horror!

Take medications, for example. (Please!) Pills for rheumatoid arthritis are often way more expensive in the US than elsewhere:

And hepatitis C:

The fastest way to increase the value of US healthcare is to reduce the price!

Physician (and Pharma, and Insurance Executive) Pay: Doing Too Well by Doing Good

Shutterstock

American physicians deserve to be paid well for their work. As a physician, myself, I know what it takes to become a doctor in the U.S. Four years of late nights in the college library in hopes of achieving a GPA commensurate with medical school admission; then four years of medical school, which makes the college work load feel light in retrospect; then, in my case, three years of residency training, where an 80-hour work week begins, making everything before feel like a vacation. And in the case of more specialized physicians than me, like orthopedic surgeons or cardiologists, clinical training continues another handful of years. Moreover, becoming a physician in the U.S. carries enormous financial costs, with many Americans graduating from medical school with six-figure debt.

So I support paying American physicians well for their labors. But how well? Is more than $535,668 the right amount for the average – the average! – orthopedic surgeon to make? Should dermatologists – whose training is far less intense and prolonged than many other physicians – make a average of $400,898?

The U.S. has a healthcare spending problem, and soaring healthcare incomes are partly responsible. Importantly, those incomes are by no means limited to physicians. In 2014, the CEO of Aetna, an American health insurance company, brought home more than $15 million. In 2012, the CEO of the nonprofit Atlantic Health System in Morristown, New Jersey made more than $10 million.

With so much money spent on medical care in the U.S., there are many people involved in the healthcare marketplace who are doing very well by doing good. Consider pharmaceutical companies, historically one of the most consistently profitable industries in the private sector. These companies make a disproportionate share of their profits in the U.S., where they charge significantly higher prices for their products than they do in most other markets. Device companies also garner significant profits in U.S. markets.

I don’t begrudge anyone who makes a lot of money doing honest, legally sanctioned work. But all this money, all the healthcare spending that leads to these high incomes, comes either from the pockets of individual patients, or from the people enrolling in private health insurance plans, or from the employers subsidizing those plans or from taxpayers who fund programs like Medicare and Medicaid. And all this money – all these personal expenses and taxes – are posing a very heavy burden on the American public.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

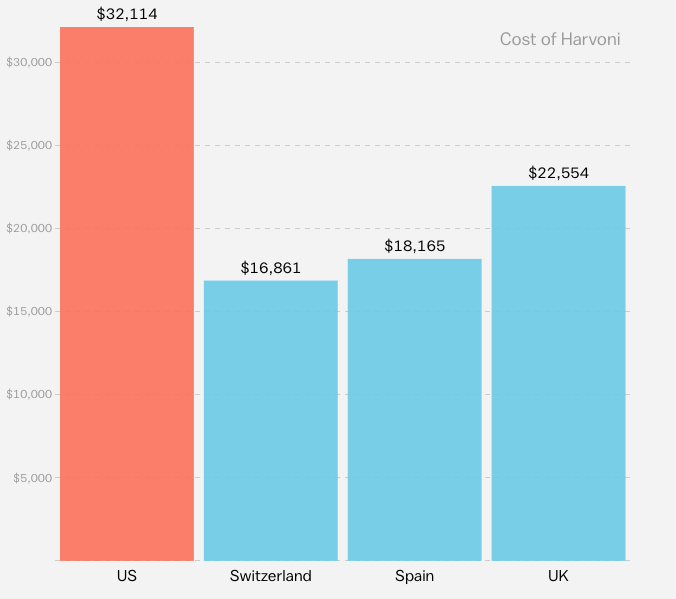

The Benefits of High Health Care Expenditures

I write frequently about the high costs of healthcare, in the U.S. and in many other parts of the world. And in general, I believe strongly that most developed countries need to look seriously at how they’re spending healthcare dollars, and make great efforts to promote high value medical care. But in trying to control healthcare costs, we must not forget about the benefits of healthcare spending. Consider this picture, from a study by Warren Stevens and colleagues, showing that countries that spent the most on cancer care have also experienced the greatest decline in cancer mortality:

Our efforts to curb healthcare spending need to account for the value of the care we spend our money on.

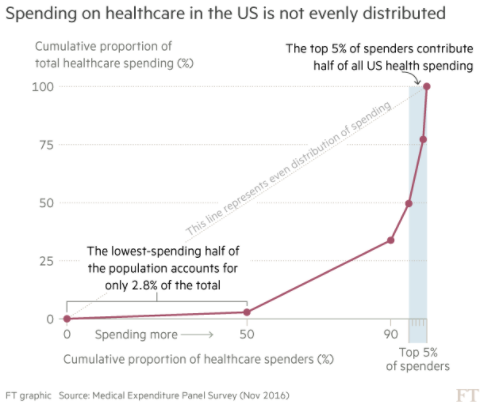

Half of Healthcare Spending: For 1/20th of the People

It is not unfair that we spend more on medical care for some people than others. After all, some people are sicker than others. If there’s anything unfair, it’s probably the uneven distribution of illness and disability. That said, the disparity in healthcare spending across people is pretty staggering. As this picture shows, courtesy of The Financial Times, half of all US healthcare spending goes to 5% of people receiving medical care:

It is not always great to be a big spender!

If We Cut Surgical Pay, Will Surgeons Cut into More People?

Shutterstock

Knee replacements are booming. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of knee replacement procedures in the U.S. doubled, to more than one million. Experts think the figure might rise 6-fold more in the next couple decades, because of our aging population. Since many people receiving knee replacements are elderly, Medicare picks up most of the cost of such procedures. It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the program is experimenting with ways to reduce the cost of each procedure.

The problem is – if healthcare providers make less money on each knee replacement they perform, they might start replacing more people’s knees than they should.

Does that sound crazy? Well consider what happened when Medicare began experimenting with a new way of paying for knee replacements – something called bundled payment. Under such reimbursement, Medicare pays one lump-sum for the total cost of a knee replacement – not just the cost of the operation but also the cost of post-operative x-rays, physical therapy, even time in nursing homes or rehab hospitals. Before bundled payment, providers received separate payments for each of these services. As a result, inefficient providers would take more x-rays than necessary, or keep patients in rehab hospitals longer than needed, and they would be rewarded for such inefficiency. Under bundled payment, providers cannot send separate bills to Medicare for hospital charges, physician fees, outpatient x-rays, and the like. Instead, they get a lump sum payment to cover all these expenses. Moreover, Medicare tracks all the knee-replacement costs for a given patient, over a 90 day period. If a patient incurs lower expenditures than expected, Medicare gives the providers part of these savings back as a reward. (Warning – this is a WAY oversimplified description of bundling.)

Early evidence suggests that bundled payments reduce the cost of knee replacements by an average of almost $1200 per patient. Save that much money on a couple million such procedures in a year, and we are looking at billions of dollars of savings. Moreover, research to date suggests that these savings don’t come at the expense of quality, at least as far as we can tell. (Quality measurement in healthcare is notoriously difficult.) For example, when knee replacements were paid for through bundled payments, there was no subsequent increase in readmission to the hospital or emergency room visits among patients whose procedures were reimbursed according to bundled payments. Same quality at a lower price – who could be against that?!

Well, caution is in order. Healthcare systems that enrolled in the bundled payment system might have saved money on each procedure, but they more than made up for that by increasing the number of procedures they performed – about three procedures more per hospital compared to hospitals not receiving bundled payments. This finding, indeed ALL these findings, are tremendously preliminary. Bundled payments are still in their infancy. Quality measurement still doesn’t capture everything we’d like it to.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

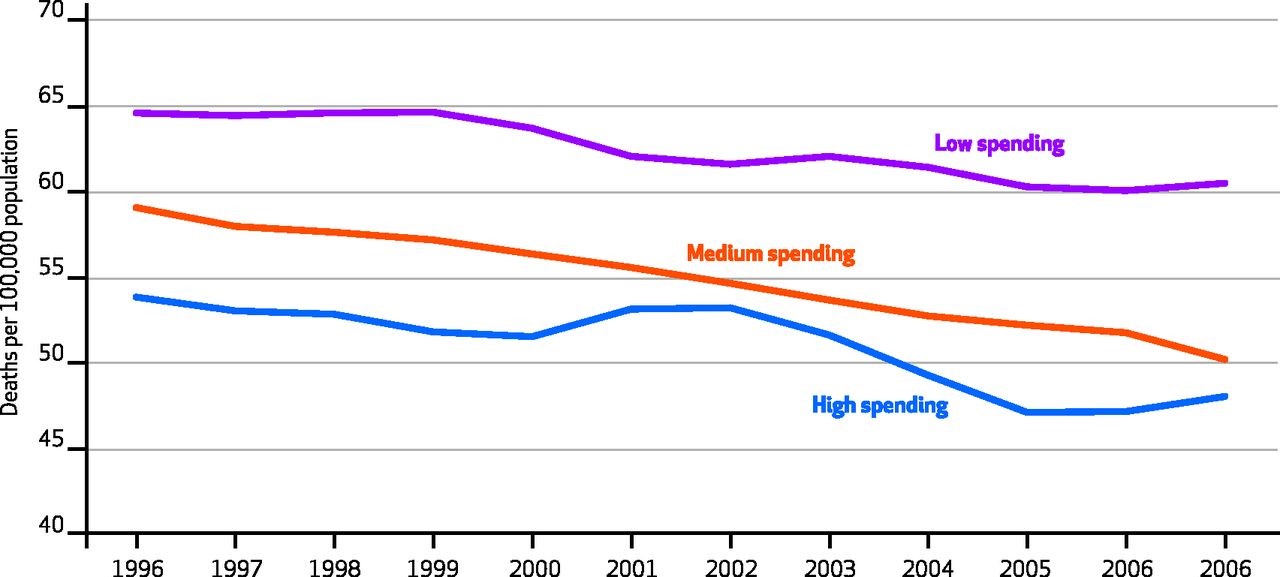

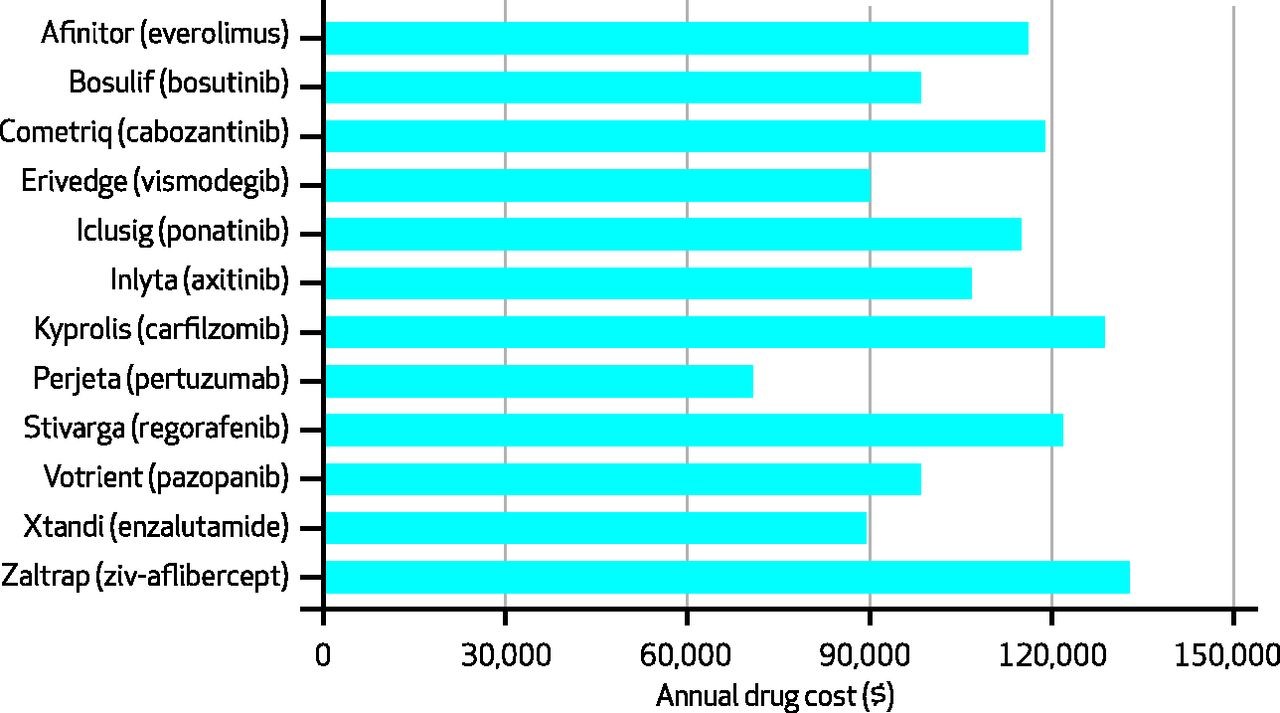

The Cost of New Cancer Drugs (In One Picture)

“Specialty drugs” – that’s what they’re called. Not the pills of old, these pharmaceuticals are often given intravenously or through injection. Often more biologic in their synthesis than chemical, they are expensive to produce and often target narrow disease processes, meaning the number of patients likely to benefit from them is much much smaller than, say, the market for blood pressure pills.

High production costs and narrow consumer market – a recipe for high prices! Consider the cost of the many specialty drugs which have entered the oncology market in recent years, here shown in a picture put together by Brad Hirsch and colleagues in Health Affairs:

Pretty amazing to look at a picture like this and find yourself asking: Why does Perjeta only cost $70,000 per year?

Medical Debt Demystified (What You Owe Isn't Necessarily What You Owe)