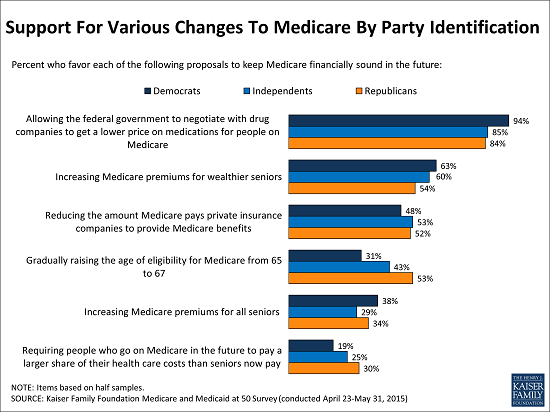

The United States Medicare program is forbidden, by law, from negotiating with pharmaceutical companies. This was part of a negotiation that was reached at the time that the government, under the leadership of George W. Bush, created Medicare Part D, to cover prescription benefits for Medicare recipients. The pharmaceutical industry was quite worried that government involvement in prescription coverage would lead to price-fixing. So they lobbied for language that would forbid such actions, and that would even limit the government from negotiating prices with Pharma companies.

The US public doesn’t support that policy. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll, the vast majority of people – Democrats, independents and Republicans – want to see such negotiations:

Now we will see who our elected representatives actually represent!

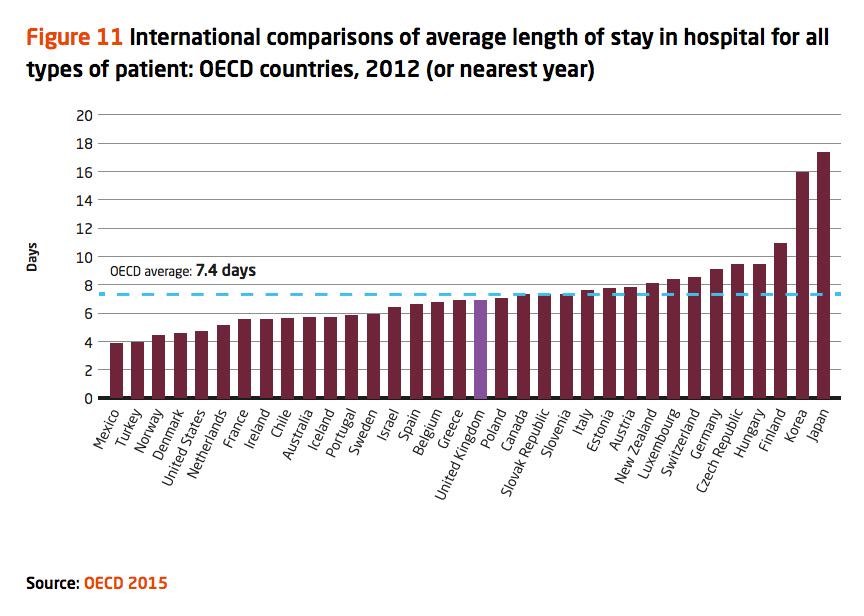

The United States of Short Hospital Stays

We spend more for medical care in the United States than just about anywhere in the world, but it’s not because people in this country get admitted to the hospital and stay for long periods of time. Instead, we have shorter length of stays in American hospitals than in the vast majority of developed countries around the world. Here is a recent picture showing these figures:

The major reason we have such short length of stay? Because in the 1980s, Medicare started paying hospitals in lump sums – a patient admitted with diagnosis X would receive a certain amount of money, regardless of whether that patient stayed in the hospital for three days, five days or longer.

I am guessing that’s not what’s happening in Korea and Japan. Anybody know why their length of stay is so… lengthy?

Paying for "Patient Satisfaction" Harms Hospitals That Care for Poor People

All else equal, it would be wonderful if hospitals had an incentive to provide high quality care. It does not seem fair to pay the same amount of money to a hospital that does a great job of caring for its pneumonia patients and one that does a lousy job. For the most part, however, third party payers like insurance companies and Medicare pay hospitals for the volume of services they provide, or volume of patients they treat, not for the quality of the care they provide.

All else equal, it would be wonderful if hospitals had an incentive to provide high quality care. It does not seem fair to pay the same amount of money to a hospital that does a great job of caring for its pneumonia patients and one that does a lousy job. For the most part, however, third party payers like insurance companies and Medicare pay hospitals for the volume of services they provide, or volume of patients they treat, not for the quality of the care they provide.

Inattention to quality is coming to an end. Hospitals are increasingly being paid in part for their performance. For example, in 2013 Medicare began a value-based purchasing program, or VBP. Under the program, Medicare withholds a percentage of payments throughout the year and then redistributes those dollars to hospitals that achieve the highest scores on a range of quality measures. In the first year of the program, this redistribution amounted to about $1 billion.

In theory, pay-for-performance makes a great deal of sense. But in practice, pay-for-performance is only as good as the quality measures used to determine performance. And Medicare’s measures, by placing significant weight on patient satisfaction scores, are hurting hospitals that disproportionately care for low income populations.

Let’s take a closer look at Medicare’s quality measures. Some are what healthcare experts call process measures, which identify whether hospitals do the right things at the right times to the right patients. When patients are admitted with heart attacks, for example, a process measure might assess how many of those patients receive aspirin and beta blockers upon discharge, or how many receive revascularization efforts in the cath lab within 30 minutes of arrival.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

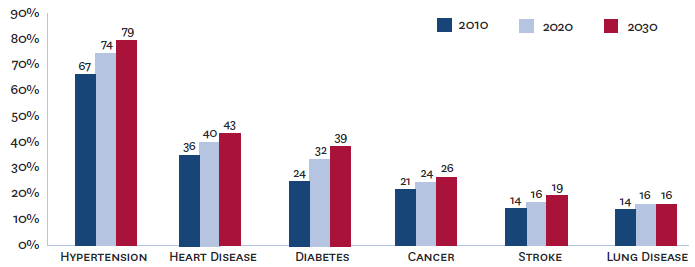

The Future of Disease – in One Picture

Are Medicare Prescription Benefits Too Stingy?

The bill she received in the mail revealed a staggering figure — $9,225 for one infusion of Avastin, a chemotherapy drug. And she would need many more such infusions. Fortunately, the dollar amount is what medical experts call a “charge,” which in normal marketplaces refers to the amount a provider expects for the good or service in question, but in healthcare means: the amount the provider reports billing to the payer, which has almost nothing to do with what we expect the payer to pay.

The bill she received in the mail revealed a staggering figure — $9,225 for one infusion of Avastin, a chemotherapy drug. And she would need many more such infusions. Fortunately, the dollar amount is what medical experts call a “charge,” which in normal marketplaces refers to the amount a provider expects for the good or service in question, but in healthcare means: the amount the provider reports billing to the payer, which has almost nothing to do with what we expect the payer to pay.

Phew! She scanned the bill more closely. The $9,000+ figure was followed by several other figures – the amount the insurance allows the doctors to charge, for example, plus (most importantly) the amount she was expected to pay out-of-pocket. As it turns out, for most Americans with private insurance, that out-of-pocket value will be quite reasonable. For Avastin, privately insured patients pay an average of $228 per treatment. That still is a lot of money for most people, but it is mere fraction of the overall cost. Insurance companies, in fact, pay an average of $4,461 for each Avastin treatment, based on data from 2012.

But there’s a very important third party payer that is not so generous, a payer that more than 55 million Americans count on for help with medical bills. That payer, of course, is Medicare. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

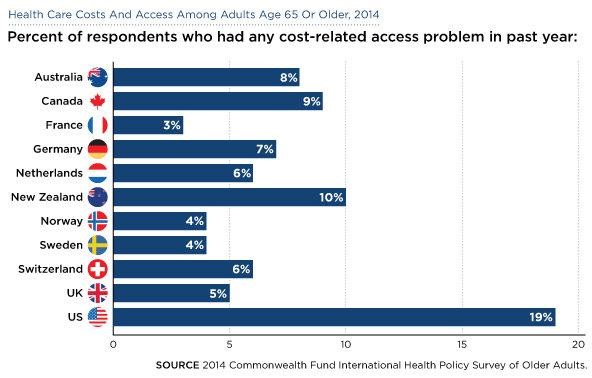

Medicare, Schmedicare

For more than half a century now, the United States has stood out among its peers in the developed world for having the largest percent of its citizens living without health insurance. But once you turn 65-years-old in America, the government has you covered. Right?

Maybe not so much. Because even after people enroll in, they still end up with lots of out-of-pocket costs, costs that often burden them to the point where they can’t afford to receive care. Take these data from the Commonwealth Fund, which show the percent of people who have difficulty obtaining medical care because of cost:

Once again, the U.S. stands as an outlier nation. Sometimes it’s not good being number one!

When It Comes to Controlling Healthcare Costs, the Government Outperforms Private Industry

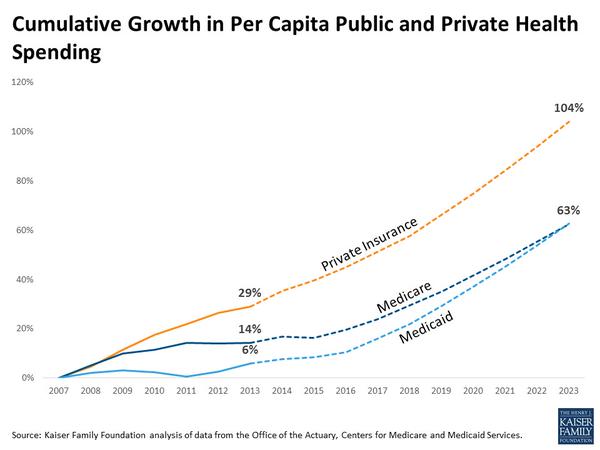

When I think of the federal government, “efficiency” is rarely the first thing on my mind. But when it comes to controlling healthcare costs, we need to consider the possibility that the federal government is better at this job than anyone else. Consider the fact that the United States dwarfs other countries in healthcare spending, despite having a more robust private insurance market than most of our peer countries. Consider this picture, from a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study. It shows a significant rise in private health spending over recent years, especially compared to growth in Medicare and Medicaid:

There’s a lot behind these numbers, much more than I’m going to cover in this short post. But I thought many of you would find these figures interesting.

Bundling Hospital Pay Without Bungling Patient Care

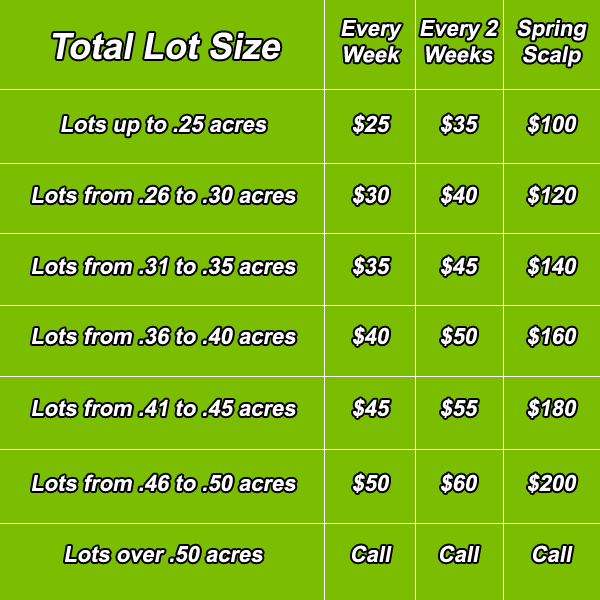

Paying someone to mow your lawn is a pretty straightforward affair. Ryan the lawn guy will look at the lawn size and maybe the hilliness of your yard and you’ll settle on a price for mowing and trimming it. When you decide to contract for Ryan’s services on a more regular basis, payment might get a little more complicated. If you pay Ryan every time he mows your lawn he might mow it more often than necessary. But that problem is easily addressed by paying him a fee to take care of your lawn for the entire growing season.

Paying a hospital to care for someone who had a stroke is not so straightforward. Imagine you are an insurance company and you decide to pay the hospital for each day the patient is in residence. With that kind of payment scheme the hospital visit might drag on indefinitely. Indeed several decades ago insurance companies in the United States primarily reimbursed hospitals on a “per diem” basis, cool kid lingo for per day. Incentivized by this reimbursement scheme, the length of stay in American hospitals was often surprisingly long for even relatively mild conditions. Think of the parallel to lawn care: pay per mowing and you can expect lots of mowings!

Healthcare payers have developed several methods to overcome this per diem/per mowing problem. I will explain these methods shortly, but first the bottom line. Figuring out how to pay for hospital care is a hell of a lot more complicated than figuring out how to pay your lawn service.

To combat the unintended consequences of per diem payment coverage, Medicare switched to per diagnosis payments in the 80s, and the insurance companies followed shortly thereafter. Under this DRG program, a hospital taking care of a patient with a severe stroke would receive appropriate payment for that diagnosis, while a hospital taking care of someone with mild pneumonia would receive a smaller payment appropriate for the typical costs of paying for that condition. Following the implementation of this type of prospective payment, length of stay in American hospitals plummeted. In response, much of medical care was shifted to post-acute care, to rehabilitation hospitals, for instance, for stroke patients, or to outpatient clinics for people with pneumonia. These non-hospital services were not covered by the diagnosis-based DRG payments, so healthcare providers had little incentive to practice parsimoniously once their patients left the hospital.

Enter bundled payments. In 2013, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, henceforth CMS, launched its Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiatives, henceforth BPCI (in case your life needs more acronyms). In the BPCI, CMS identified 48 clinical conditions that qualify for bundled payments, meaning participating healthcare providers would receive payments designed to cover not only hospital care for the condition in question, but money to pay for all healthcare related services they receive for the next 30 days. Unsurprisingly, not all hospitals are eager to join this program. For starters, the hospitals have to be financially integrated with post hospital providers. If patients receiving stroke care at Our Lady of Acute Care Hospital receive post-acute care from a hodgepodge of rehabilitation facilities, many of which have no connection to the hospital, then coordinating payments will be a disaster. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

What Happens When We Penalize Hospitals For Harming Patients?

I recently had surgery to relieve an impingement of my left hip. I suffered a complication of the procedure in the hospital where I received the surgery performed follow-up care to treat the complication. As I lay on the table receiving that second treatment I wondered – okay, I mainly wondered “are they really going to stick a needle there?!,” – but I also asked myself “how strange is it that when patients experience complications, hospitals are rewarded with money to perform additional procedures?”

Since 2008, Medicare has been denying payment to hospitals to treatments they provide as a result of preventable complications. For example, when patients are immobilized from illness or disability, they sometimes develop pressure ulcers – their skin breaks down where the weight of their body meets the bed or wheelchair. Pressure ulcers are a big deal. A red spot on a patient’s backside can quickly turn into a sore, then into an ever expanding mass of tissue damage and infection. Christopher Reeve, the actor paralyzed after a horseback riding injury, died from complications of a pressure ulcer.

Pressure ulcers can almost always be avoided by appropriate nursing care. If patients are turned regularly with appropriate bedding and wheelchairs, no single spot will take the brunt of their weight 24 hours a day, and therefore no pressure ulcers will develop. In recognition of the preventability of pressure ulcers, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals for the services they provide to treat such problems. The same goes for catheter associated urinary tract infections, which I’ve written about before, as well as catheter associated blood stream infections and injurious patient falls.

Medicare’s non-reimbursement strategy makes a great deal of sense. At a minimum, it will save the program money. But will the program have additional benefits? Specifically, now that hospitals are no longer financially rewarded for causing these complications, will this reduce the incidence of these avoidable events? (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Proven: People Don't Take Medicine They Can't Afford

Cholesterol pills are one of the great medical advances I’ve witnessed during my professional career. I am talking specifically about a category of medications called statins, drugs like Lipitor and Pravachol. These drugs have prevented probably hundreds of thousands of heart attacks and strokes. Only one problem with these drugs, however: statins won’t help people who don’t take them. And according to a study in the prestigious Annals of Internal Medicine, when physicians prescribe trade versions of statins rather than generics, the extra cost dissuades many people from filling the prescription.

Cholesterol pills are one of the great medical advances I’ve witnessed during my professional career. I am talking specifically about a category of medications called statins, drugs like Lipitor and Pravachol. These drugs have prevented probably hundreds of thousands of heart attacks and strokes. Only one problem with these drugs, however: statins won’t help people who don’t take them. And according to a study in the prestigious Annals of Internal Medicine, when physicians prescribe trade versions of statins rather than generics, the extra cost dissuades many people from filling the prescription.

If physicians want to help their patients, they need to prescribe affordable versions of accepted medical interventions.

The study was led by Joshua Gagne, a pharmaco-epidemiologist (a person who lives and breathes hardcore data on medications and population health) at Harvard (an up and coming university located, I think, somewhere near Boston). Gagne and colleagues analyze data from Medicare patients who got their prescription benefits from CVS Care Mark. (To read the rest of this post and leave comments, please visit Forbes.)