“Specialty drugs” – that’s what they’re called. Not the pills of old, these pharmaceuticals are often given intravenously or through injection. Often more biologic in their synthesis than chemical, they are expensive to produce and often target narrow disease processes, meaning the number of patients likely to benefit from them is much much smaller than, say, the market for blood pressure pills.

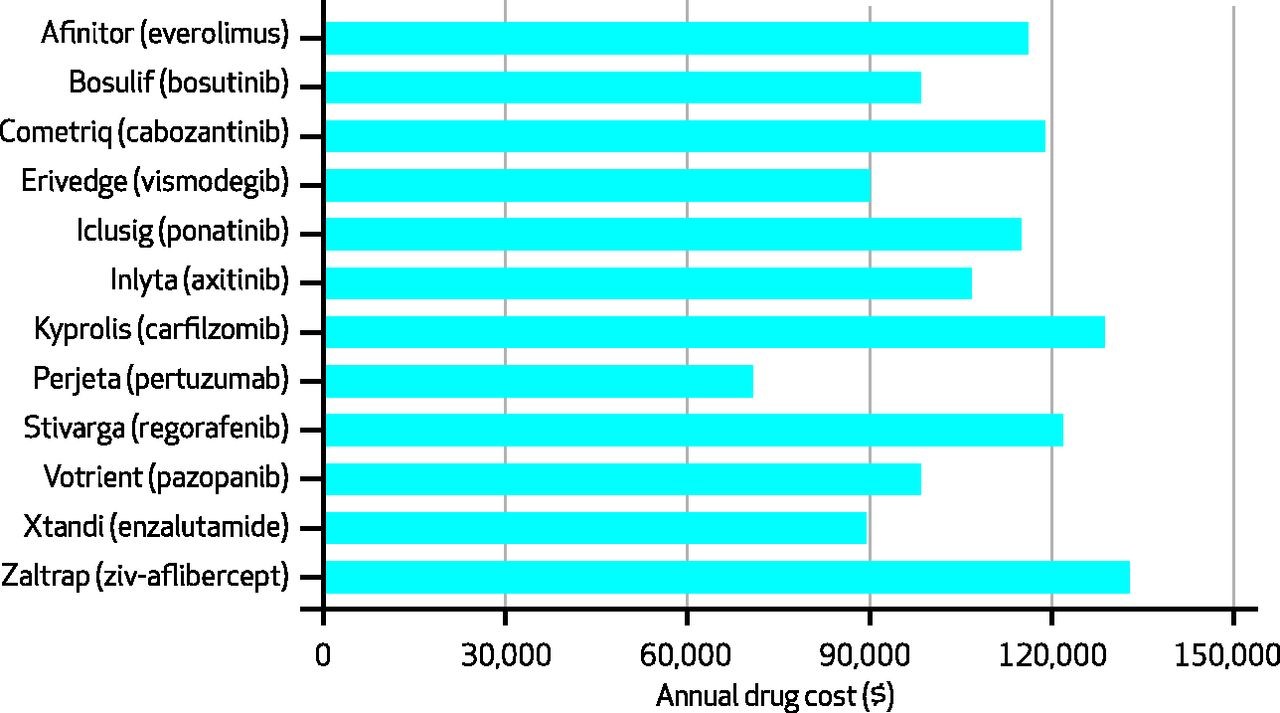

High production costs and narrow consumer market – a recipe for high prices! Consider the cost of the many specialty drugs which have entered the oncology market in recent years, here shown in a picture put together by Brad Hirsch and colleagues in Health Affairs:

Pretty amazing to look at a picture like this and find yourself asking: Why does Perjeta only cost $70,000 per year?

Here's Why Insulin Is So Expensive, And How To Reduce Its Price

She drew the life-saving medication into the syringe, just 10cc of colorless fluid for the everyday low price of, gulp, several hundred dollars. Was that a new chemotherapy, specially designed for her tumor? Was it a “specialty drug,” to treat her multiple sclerosis? Nope. It was insulin, a drug that has been around for decades.

The price of many drugs has been on the rise of late, not just new drugs but many that have been in use for many years. Even the price of some generic drugs is on the rise. In some cases, prices are rising because the number of companies making specific drugs has declined, until there is only one manufacturer left in the market, leading to monopolistic pricing. In other cases, companies have run into problems with their manufacturing processes, causing unexpected shortages. And in infamous cases, greedy CEOs have hiked prices figuring that desperate patients would have little choice but to purchase their products.

Then there’s the case of insulin. No monopoly issue here – three companies manufacturer insulin in the U.S., not a robust marketplace, but one, it would seem, that should put pressure on producers. No major manufacturing problems, either. There has been a steady supply of insulin on the market for more than a half century. And there haven’t been any insulin company executives I know of who have been hustled in front of grand juries lately.

Yet insulin prices are rising to dizzying heights. In 1991, according to a recent study inJAMA, state Medicaid programs typically paid less than $4 for a unit of rapid acting insulin. After accounting for inflation, that price has quintupled in the meantime.

What explains the gravity-defying cost of insulin? I am not an expert on pharmaceutical pricing, but a few factors go a long way to explaining insulin prices. First, the insulin marketplace has been characterized by continual product upgrades. You see, there’s not just one chemical that makes up all insulin products. Instead, insulin treatments are a family of products, each with slightly different chemical makeup that influences things like how quickly the medicine is absorbed into the blood stream. Manufacturers have been toying with insulin molecules since at least 1936, when the manufacturer added protamine to insulin molecules to extend the duration of the chemical’s activity. In the 1960s, companies began synthesizing insulin, rather than harvesting it from pancreatic tissue. In the late 70s, they began producing insulin through genetic engineering.

So when I said that the price of insulin had quintupled over the decades, we have to keep in mind that today’s insulin is not the same as yesterday’s.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Finally: Something Republicans and Democrats Can Agree On

The United States Medicare program is forbidden, by law, from negotiating with pharmaceutical companies. This was part of a negotiation that was reached at the time that the government, under the leadership of George W. Bush, created Medicare Part D, to cover prescription benefits for Medicare recipients. The pharmaceutical industry was quite worried that government involvement in prescription coverage would lead to price-fixing. So they lobbied for language that would forbid such actions, and that would even limit the government from negotiating prices with Pharma companies.

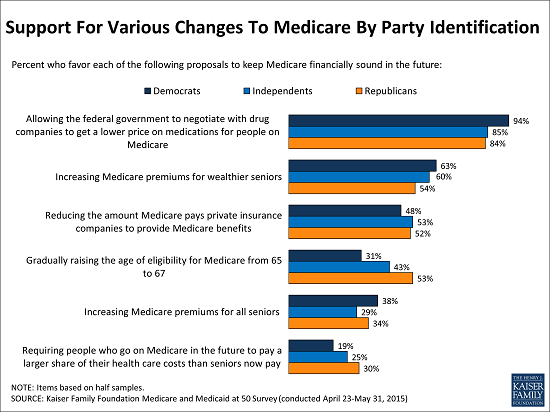

The US public doesn’t support that policy. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll, the vast majority of people – Democrats, independents and Republicans – want to see such negotiations:

Now we will see who our elected representatives actually represent!

The High Price of Affordable Medicine

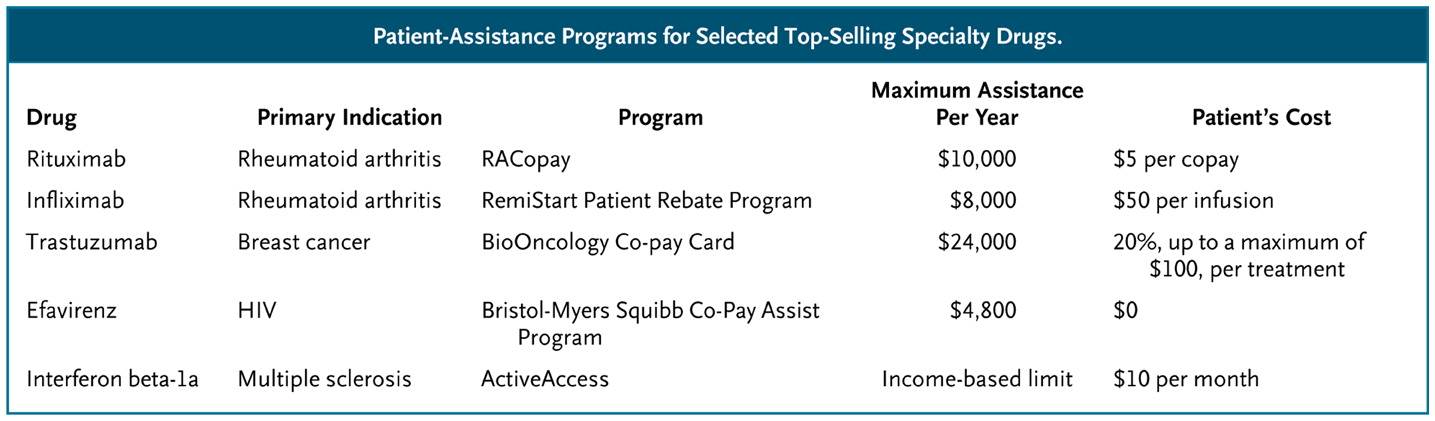

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

The high cost of such blockbuster specialty drugs creates significant financial burden for many patients. When a drug costs $90,000 per year, and a patient pays 10% of that cost, we are talking about a serious chunk of change. Not surprisingly, as these out-of-pocket costs rise, so too do the rates of “non-adherence,” medical lingo for “the patients didn’t take the medicines that I, their doctor, thought they should take.” Non-adherence used to be called noncompliance, which sounded too paternalistic. Now some experts are shifting to an even less judgmental language of “medication abandonment.” Indeed, here is a picture of the likelihood that patients will stop taking specialty drugs as a function of their out-of-pocket costs:

What can we do to help patients afford these medications?

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)