A recent study of men with early-stage prostate cancer found no difference in 10-year death rates, regardless of whether their doctors actively monitored the cancers for signs of growth or eradicated the men’s cancers with surgery or radiation.

What does this study mean for patients? Based on research we have conducted on prostate cancer decision-making, the implications are clear: Patients need to find physicians who will interact with them the way a good financial counselor would, taking the time to understand them well enough to help them find the treatment that fits their goals.

Imagine a couple in their 40s who ask a financial counselor for advice on retirement planning, and the counselor tells them how much to invest in domestic and foreign stocks versus bonds versus real estate without asking them about their goals. A good counselor would find out what ages the couple wishes to retire at, what kind of retirement income they hope to live off of, how much risk they are willing to take to achieve their goals, and how devastated they would be if their high return investments go south, forcing them to delay retirement or reduce their retirement spending.

Far too often in medical care, physicians don’t behave like good financial counselors–they give treatment recommendations without taking the time to understand their patients’ goals. Consider early-stage prostate cancer, a typically slow-growing tumor that is not fatal for the vast majority of patients who receive the diagnosis. In some men, the tumor lies indolent for decades.

For that reason, men sometimes choose to monitor their cancers–have their doctors conduct regular blood tests or biopsies to see if the tumor is beginning to spread. Such monitoring has the advantage of being relatively noninvasive, but it can create anxiety for patients who wonder, every six months, whether their next checkup will bring bad news.

For that reason, some men prefer active treatments like surgery or radiation that eradicate their cancers and therefore reduce cancer-related anxiety. But these more active treatments have their own downsides–each treatment is relatively arduous, and they can cause both erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

The choice between active treatment and active monitoring depends on a patient’s goals–on how they view the trade-off between outcomes like cancer-related anxiety and erectile dysfunction. When counseling patients with early-stage prostate cancer, physicians need to help patients focus on these trade-offs.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Out of Control Physicians: Too Many Doctors Doing Too Many Things to Too Many Patients

My father is 92 years old, and I am beginning to wonder whether the best thing for his health would be to stay away from doctors. That’s because well intentioned physicians often expose their elderly patients to harmful and unnecessary services out of habit. That’s certainly the message I absorbed after reading a recent issue of JAMA Internal Medicine that published three studies documenting the worrisome frequency with which internists like me over-test and over-treat our patients. I am going to briefly describe these three studies before laying out some ideas about what’s going on here.

One study explored the use of PSA screening among men with limited life expectancy. The PSA blood test is used to screen men for prostate cancer. The test is controversial, with some groups saying there is no evidence it benefits anyone and others saying it is a crucial way to reduce prostate cancer deaths. Despite this controversy, almost everyone agrees that when people have limited life expectancy–when, because of age and other illnesses, they probably have fewer than five years to live–the PSA test does more harm than good. But some physicians nevertheless continue to order PSA tests, even in men close to the end of their lives.

The study, which analyzed data from Veteran’s Affairs medical centers, found out that patients receiving care from “attending physicians”–more senior physicians–were more likely to receive harmful PSA tests than patients receiving care from physicians still in training. Indeed, 40% of patients expected to live five or fewer years received PSA tests from experienced physicians, versus only 25% receiving care from trainees :

The second study looked at carotid artery imaging in people 65 years or older. The carotid arteries are the large vessels on either side of your neck, the ones you can feel your pulse on. They are the main supply of blood to the brain. People who get blockages in their carotid arteries are at risk for strokes.

Carotid imaging with tests like ultrasound can identify narrowing of these important arteries, potentially revealing partial blockages in time to fix them before they fully occlude. In the old days, I’d place my stethoscope on a patient’s neck to listen to the harsh sound of blood squeezing its way through these blockages. Upon hearing a worrisome whoosh, I’d send my patient for imaging and then, if my suspicions were warranted, would refer the patient to a neurovascular surgeon, who would decide whether to perform a procedure to open up the artery.

But now, we physicians are being told to be more cautious. The benefits of all these tests and treatments aren’t so clear in many patients. The risks of the surgery can outweigh the benefits in people with no history of stroke or stroke-like symptoms. Nevertheless, many physicians continue to test and treat aggressively.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Doctors Can't Be Trusted to Tell Patients Whether They Should Receive Robotic Surgery

Patients often rely on physicians for information about their treatment alternatives. Unfortunately, that information is not always objective.

Consider a man with early stage prostate cancer interested in surgical removal of his tumor, but uncertain whether it is better for the surgery to be performed with the help of robotic technology. He asks his surgeon for advice, and the surgeon explains that, while robotic surgeries have some advantages (smaller incisions, less blood loss), the advantages are “tiny and unimportant.” And besides: “You do have some smaller incisions with the robotic, but if you added up all the incisions from all the ports and from the incision to remove the prostate itself, it ends up equaling about the same incision length.”

Can that physician’s description of robotic technology be trusted?

My friend and colleague Angie Fagerlin led a study of prostate cancer decision-making that took place across four Veterans Affairs medical centers. As part of that study, she audio-recorded clinical interactions between patients and their surgeons. In some of these interactions, patients asked about the pros and cons of robotic surgery.

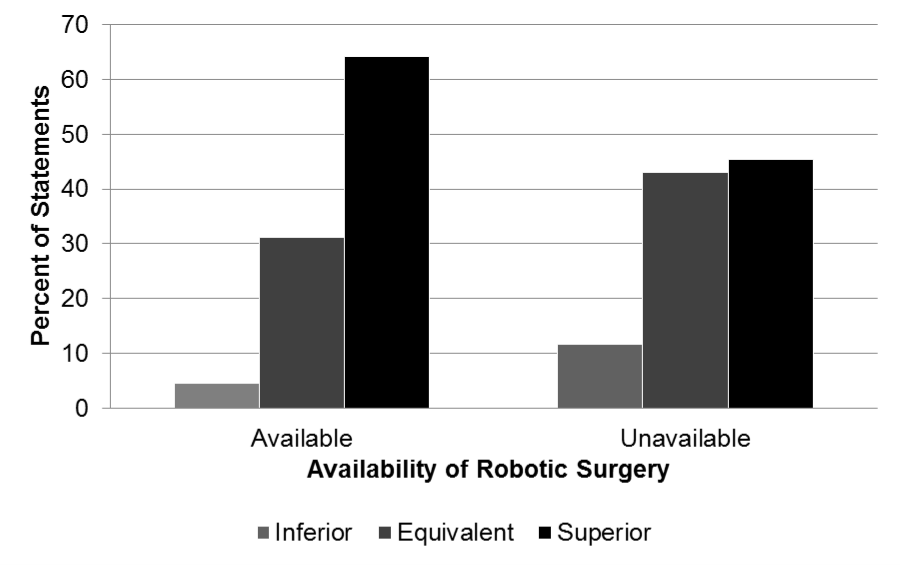

As it turns out, some urologists worked at VAs that had access to robotic equipment and others did not. In an analysis lead by Karen Scherr (an MD/PhD student at Duke), our research team discovered that surgeons who had access to the robot were more generous in describing its advantages over standard “open” surgery. When no robot was available, physicians downplayed its advantages. This is illustrated in the following figure, showing the percent of statements physicians made indicating that robotic surgery was inferior, equivalent or superior to traditional surgical approaches:

Importantly, I do not think physicians are willfully misleading patients about the pros and cons of robotic surgery. Instead, I think most physicians believe the robot is better (in the right hands) but when it is unavailable, doctors try to reassure patients that they will still receive state-of-the-art care. For example, one patient expressed anger that the robot was not available at his VA Hospital: “you see, that’s what’s so stupid about the VA!” The physician tried to assuage his concerns: “If you look at long-term outcomes related to cancer and cancer recurrence,” the surgeon said, “there has really been no difference. That’s why the VA system has not really invested in the robot.”

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Which Cancers Do We Spend Most of Our Money On?

There has been lots written lately about the soaring cost of cancer care. You’re spending a lot on cancer recently in part because of many wonderful new treatments that come with a substantial price tag.

But there has been less chatter about which cancers we are spending money on. Here’s a nice picture illustrating that information. I came across it courtesy of Ryan Nipp:

I’d love to see a breakdown of this information as cost per patient. Please let me know if you have access to those data.

You Thought Innovation Was Hard, How about De-Innovation?

David Asch and I recently published an article in Health Affairs on the challenge of getting healthcare practitioners to stop doing things they are accustomed to doing, even when the evidence that those things are harmful becomes overwhelming. Here is a teaser from that article, and a link to the full piece:

David Asch and I recently published an article in Health Affairs on the challenge of getting healthcare practitioners to stop doing things they are accustomed to doing, even when the evidence that those things are harmful becomes overwhelming. Here is a teaser from that article, and a link to the full piece:

As hard as it may be for clinicians to adopt new practices, it is often harder for them to “de-innovate,” or give up old practices, even when new evidence reveals that those practices offer little value. In this article we explore recent controversies over screening for breast and prostate cancer and testing for sleep disorders. We show that these controversies are not caused solely by a lack of clinical data on the harms and benefits of these tests but are also influenced by several psychological biases that make it difficult for clinicians to de-innovate. De-innovation could be fostered by making sure that advisory panels and guideline committees include experts who have competing biases; emphasizing evidence over clinical judgment; resisting “indication creep,” or the premature extension of innovations into unproven areas; and encouraging clinicians to explicitly consider how their experiences bias their interpretations of clinical evidence.

What Mammograms Teach Us About Wildfires, Floods, and Tornadoes

In the wake of the horrific floods that struck Colorado recently, many people have debated whether global warming is to blame. The same goes for wildfires that hit that state this summer and for the massive tornado that struck in Oklahoma this spring. In the wake of that tornado, for instance, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse from Rhode Island claimed that Republican opposition to climate change legislation was at fault, for trying to “protect the market share of polluters.” Senator Barbara Boxer was confident about the cause of the terrible twister too: “This is climate change” she said.

In the wake of the horrific floods that struck Colorado recently, many people have debated whether global warming is to blame. The same goes for wildfires that hit that state this summer and for the massive tornado that struck in Oklahoma this spring. In the wake of that tornado, for instance, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse from Rhode Island claimed that Republican opposition to climate change legislation was at fault, for trying to “protect the market share of polluters.” Senator Barbara Boxer was confident about the cause of the terrible twister too: “This is climate change” she said.

The same finger pointing occurred after super storm Sandy, with some people even claiming that global warming could make storms like Sandy into the new normal, occurring as often as every other year, and Governor Chris Christie just as adamantly denying that global warming played any role in this storm.

The problem with these debates is familiar to those of us in the medical community who have followed controversies about breast cancer screening—people mistakenly and all too understandably seek out explanations for individual events when science can only tell us about aggregate truths. For the same reason we cannot tell whether an individual mammogram saved a woman’s life, we cannot determine whether any specific storm is the result of climate change. Instead, we are left with what we can learn from statistics.

Wondering why we don’t know whether a specific mammography test saved a woman’s life? …(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Is There a Smart Way to Use the New Oncotype Prostate Cancer Test?

On May 8th, the makers of the oncotype DX Prostate Cancer Test presented results of a large study demonstrating that their test can help men decide whether their prostate cancer carries a low enough risk of progression to forgo surgical or radiation therapy, two treatments that typically eradicate prostate cancers but also cause most men to experience impotence and incontinence.

On May 8th, the makers of the oncotype DX Prostate Cancer Test presented results of a large study demonstrating that their test can help men decide whether their prostate cancer carries a low enough risk of progression to forgo surgical or radiation therapy, two treatments that typically eradicate prostate cancers but also cause most men to experience impotence and incontinence.

Lacking such a test, many men have felt compelled to receive these aggressive treatments even though they know that most men in their position—with low grade cancer localized to the prostate—will not experience aggressive, metastatic disease. Low grade tumors—what are called Gleason 6 and 7 tumors based on how they look under a microscope—do not usually cause fatal illness.

But there are a couple problems with our current staging system, at least in the minds of most patients. It’s phrases like “don’t usually cause fatal illness”. Those are troublingly vague words for someone who has just found out he has a cancer diagnosis. It must mean that some of those tumors turn nasty.

Enter the Oncotype test. If the test is as good as experts hope it to be (warning: the results have not passed peer review muster yet), if the test better identifies safe tumors that have almost no chance of spreading, then men should be able to avoid those nasty treatments. And they should also be able to avoid the costs of being monitored every six months with prostate blood tests and biopsies.

But will human psychology interfere with optimal use of the Oncotype test? … (Read more and view comments at Forbes)