The video below is not super high quality, but it captures a talk I gave in Lima Peru recently, a very personal talk that also reveals some of the dangers of assuming that medical decision making will go swimmingly well as long as patients are informed and empowered. Check it out.

(Click here to view comments)

Another Review of Critical Decisions

Here’s a link to a review of Critical Decisions published in a journal called Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics. The reviewer had some nice things to say, but felt it wasn’t theoretical enough for his liking. Not surprising given that I wrote the book for a general audience, and not for an academic one. But this kind of review does motivate me to try to write some more spin-off articles, aimed at academic audiences, to go into some of the theoretical issues I raise in Critical Decisions in a more thorough, and academic manner. Good to remember in the meantime: writers have to know their audience. And my goal in writing Critical Decisions was to reach a broad one, not just an academic one.

Why Do Patients Take Their Doctor's Advice?

Is it the white coat? That’s what I wondered in medical school when I would find patients asking me for advice on topics they simply had to know more about than me. Mothers would ask me how to get their newborn babies to sleep through the night, asking me even though the one time I babysat I fell asleep on the family’s couch only to be woken up by their 4-year-old, asking me whether it was okay if she went to bed now.

Is it the white coat? That’s what I wondered in medical school when I would find patients asking me for advice on topics they simply had to know more about than me. Mothers would ask me how to get their newborn babies to sleep through the night, asking me even though the one time I babysat I fell asleep on the family’s couch only to be woken up by their 4-year-old, asking me whether it was okay if she went to bed now.

Elderly men and women would ask me how to cope with fear of dying, asking me even though at the ripe old age of twenty-four I had not ever experienced that feeling.

Middle aged women would ask me whether I thought they should get mastectomy or lumpectomy to treat their newly diagnosed breast cancers, asking me even though I knew the decision was not a pure medical judgment but instead depended on their values, and whether they felt that preserving part of their breast was worth six weeks of radiation treatment.

I thought it was simply the white coat and all the knowledge it symbolized. But having just read Francesca Gino’s wonderful new book, Sidetracked: Why Our Decisions Get Derailed, and How We Can Stick to the Plan, I have a much richer understanding of when, and why, people choose to rely on advice… (Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Abraham Lincoln on Perspective Taking

I write frequently about the importance of perspective taking in clinician/patient interaction. Seeing the world through other people’s eyes is also a crucial moral and political skill. No surprise then that Abe Lincoln showed great perspective taking abilities. Consider these words, from an 1854 speech on slavery:

I write frequently about the importance of perspective taking in clinician/patient interaction. Seeing the world through other people’s eyes is also a crucial moral and political skill. No surprise then that Abe Lincoln showed great perspective taking abilities. Consider these words, from an 1854 speech on slavery:

I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation.

Would love it if feuding politicians could embrace this wisdom more often today.

(Click here to view comments)

New Review of Critical Decisions

A review of Critical Decisions was recently published in The American Journal of Bioethics. You can check it out here.

A review of Critical Decisions was recently published in The American Journal of Bioethics. You can check it out here.

(Click here to view comments)

Should Your Doctor Pray With You?

“I can fix this.”

“I can fix this.”

The neurosurgeon was nothing if not confident.

“The cyst is pushing on your spinal cord. If it continues to expand, it will damage your nerves and you may lose the ability to walk. But I can remove the cyst, and cure you.”

The patient was a business school professor, a man comfortable with risk-benefit ratios and complex decisions. He probed for more information. The surgeon was happy to provide him with some numbers.

“There’s an 80 percent chance you’re cured. You sail through surgery. But there is a 3 percent chance of a very bad outcome — death or paralysis. And then a 15-17 percent chance of more minor side effects, things you will recover from.”

The professor was not happy to learn these numbers, but given the inevitability of paralysis if he didn’t get the procedure, the 3 percent figure sounded well worth the risk. So he agreed to undergo the surgery.

Days later, he lay on a bed in the pre-operative suite, an IV in his arm and blue hospital socks adorning his feet. The neurosurgeon came by to check in on him. He re-explained the procedure and its risks. The professor was unmoved. He understood the situation and felt good about his chances. Then, just when it looked like the surgeon would head back to the operating room, he instead lowered his head and held the professor’s hands… (Read more and view comments at The Atlantic)

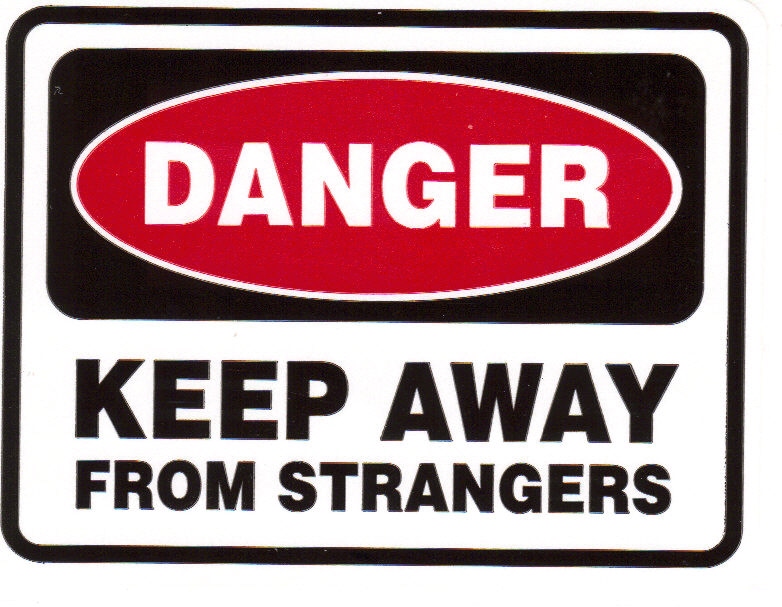

Should Doctors Give Medical Advice to Strangers over Email?

Recently I received an email from someone I have never met, who asked me the following:

Recently I received an email from someone I have never met, who asked me the following:

“Could you refer me to any current study results on Arimidex (Anastrozole)? My oncologist is not helpful. My oncotype dx said I have 9% chance of recurrence and with Arimidex for 5 years that is reduced to 4.5 %. Not sure it is worth it?

I remember being mocked because I wouldn’t take HRT in 1996. He chided me that after my uterus was removed I needed it for my heart. Turns out that was not true. Makes me wonder.

Any current info would be helpful.”

One of the joys of writing for broad audiences is that I get to interact with people outside the worlds of academia and medical practice. And since writing Critical Decisions, I have received an increasing number of emails from people who say the book has helped them through their own medical journeys. On the other hand, that sometimes puts me in the awkward position of trying to figure out how to handle anonymous requests for medical advice… (Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Helping Your Doctor Help You: An Interview with Project Millennial (Part 2)

KARAN: You referred to patient education earlier, not just in terms of treatment information but also the types of questions to be asking. But what about the former? Our generation is definitely comfortable using technology to look up health information, and we get a ton of information through news, magazines, and the general media. But not all of it’s good. So how do you recommend people sift through the good and bad information out there, when they’re trying to inform themselves before a visit to the doctor.

KARAN: You referred to patient education earlier, not just in terms of treatment information but also the types of questions to be asking. But what about the former? Our generation is definitely comfortable using technology to look up health information, and we get a ton of information through news, magazines, and the general media. But not all of it’s good. So how do you recommend people sift through the good and bad information out there, when they’re trying to inform themselves before a visit to the doctor.

DR. UBEL: Of course, the education system should help people learn how to objectively look at things and help them when things go over their heads.

But the other thing I’d say is, print out and bring in the stuff that you see online, show it to your doctor, and let them tell you what’s right or wrong about it. Then they’ll know what you care about more than they did before, which is really valuable. Your doctor shouldn’t be threatened when you bring these materials in; they should be happy that you’re helping focus the visit on the topics you care about. If you’ve got misconceptions that are affecting the way you’re behaving, like what pills you’re taking or not taking, the doctor should be happy to have a chance to address those misconceptions.

So: print it out; bring it in.

Speaking broadly, younger patients are probably more likely to have sporadic relationships with the healthcare system—moving around a lot, without a constant PCP, potentially also going to MinuteClinics more often. As decision-makers, do you think that affects the things we should be thinking about …

(Read more and view comments at Project Millennial)

Helping Your Doctor Help You: An Interview with Project Millennial

KARAN: Though I hope our readers all read your book, for those who haven’t just yet, I want to start with an example that touches on the issues it discusses. I recently got a bad ankle sprain. The following week, I went to a local orthopedic surgeon for it. He was a very old-school doctor; before even talking about treatment options at all, he was getting his stuff out to give me a cortisone shot for my ankle. I was still trying to give him my history and symptoms and I had to stop to ask what he was doing. It was a little scary; I had no desire to get a shot, and from whatever little I know, I think cortisone might’ve even hurt more than it helped. But I’m obviously not residency-trained in orthopedic surgery, so I didn’t feel right questioning his opinion. So while I have seen how the patient autonomy movement has affected the way doctors are ethically trained, which you discuss in your book, I still think there are a lot of doctors who fit the old mold. As a patient, especially a young and inexperienced patient, it’s difficult sometimes to know how to respond.

KARAN: Though I hope our readers all read your book, for those who haven’t just yet, I want to start with an example that touches on the issues it discusses. I recently got a bad ankle sprain. The following week, I went to a local orthopedic surgeon for it. He was a very old-school doctor; before even talking about treatment options at all, he was getting his stuff out to give me a cortisone shot for my ankle. I was still trying to give him my history and symptoms and I had to stop to ask what he was doing. It was a little scary; I had no desire to get a shot, and from whatever little I know, I think cortisone might’ve even hurt more than it helped. But I’m obviously not residency-trained in orthopedic surgery, so I didn’t feel right questioning his opinion. So while I have seen how the patient autonomy movement has affected the way doctors are ethically trained, which you discuss in your book, I still think there are a lot of doctors who fit the old mold. As a patient, especially a young and inexperienced patient, it’s difficult sometimes to know how to respond.

DR. UBEL: I don’t think this is an old/young issue. If anything, people tend to think their older patients are more deferential than the younger ones. Most people in their 20s are more into the “consumer” mindset than older people who grew up in the “doctor knows best” era. But when you are young, the age difference between you and the doctor is bigger, so that could make it harder to be assertive when interacting with your doctor. But patients ought to feel they can assert themselves because, even for mundane issues, any time there’s more than one way to go about it, the patient deserves to know what their alternatives are and to be a partner in the decision. So what happened to you is not the best possible medical care. Whether the doctor made the right choice, that’s one thing. But if he didn’t say “One thing we could do is this, but you should know, there are other alternative. For example, if you don’t want to get a shot, we could just give it time, etc.” If the physician didn’t speak to you that way, that’s a problem… (Read more and view comments at Project Millennial)

Are Doctors Afraid to Talk Math with Their Patients?

Before patients can become savvy consumers of healthcare, they need information about their healthcare choices. Too often, such information is nearly impossible to get, especially when it requires doctors to give patients useful statistics about things like treatment side effects.

Before patients can become savvy consumers of healthcare, they need information about their healthcare choices. Too often, such information is nearly impossible to get, especially when it requires doctors to give patients useful statistics about things like treatment side effects.

Since publishing Critical Decisions this fall, I have received a number of emails from readers who have recognized their own medical histories in the pages of my book. I received a particularly entertaining email from a professor in Canada, who relayed the following story.

He was in an emergency room suffering from kidney stones. And for those of you who have never experienced kidney stones, take it from my mother: they are insanely painful. “Worse than having twins,” she told me… (Read more and view comments at Forbes)