I recently posted on how public park builder, Robert Moses, used the psychology of sunk costs to get more money for his ambitious projects. Once those projects were complete, he also used social psychology to keep them clean. It had to do with the directions he gave to the people hired to clean up the Parks:

I recently posted on how public park builder, Robert Moses, used the psychology of sunk costs to get more money for his ambitious projects. Once those projects were complete, he also used social psychology to keep them clean. It had to do with the directions he gave to the people hired to clean up the Parks:

Patrolling the Boardwalk, conspicuous in snow-white sailor suits and caps, they hurried to pick up dropped papers and cigarette butts while the droppers were still in the vicinity. They never reprimanded the culprits, but simply bent down, picked up the litter, and put it in a trash basket. To make the resultant embarrassment of the litterers more acute, Moses refused to let the Courtesy Squatters use sharp-pointed sticks to pick up litter without stooping. He wanted the earnest, clean-cut college boys stooping, Moses explained to his aides. It would make the litterers more ashamed.

Once again, he displayed how a brilliant understanding of human nature comes in handy, when you are trying to influence people.

The war of 1812 was sometimes called “Madison’s war” by those who opposed the President’s call for military action against Great Britain. A whole slew of grievances was building up between the two countries, especially with Britain’s bullying behavior in the seas. But it was also clear that Pres. Madison was itching for war, and that he led us into a war that could have been avoided. That was certainly the opinion of Henry Adams, when writing a history of the United States about a century later:

The war of 1812 was sometimes called “Madison’s war” by those who opposed the President’s call for military action against Great Britain. A whole slew of grievances was building up between the two countries, especially with Britain’s bullying behavior in the seas. But it was also clear that Pres. Madison was itching for war, and that he led us into a war that could have been avoided. That was certainly the opinion of Henry Adams, when writing a history of the United States about a century later: I have long been a fan of single sentence paragraphs.

I have long been a fan of single sentence paragraphs. In 1925, a handful of extremely wealthy Long Island residents tried to thwart state plans to run highways from New York City through Long Island to beaches that the masses could enjoy. These wealthy people were understandably upset, that part of their property would be taken away to make room for highways and the like. But they resisted to the point of inflexibility, and the millions of lower and middle class New York City residents who hoped to find weekend refuge from summer heat looked like they would be shut down by a few dozen multimillionaires. But Gov. Al Smith was not happy with this arrangement. And in a speech arguing in favor of these parks and beaches, he also made some pretty profound statements about democracy:

In 1925, a handful of extremely wealthy Long Island residents tried to thwart state plans to run highways from New York City through Long Island to beaches that the masses could enjoy. These wealthy people were understandably upset, that part of their property would be taken away to make room for highways and the like. But they resisted to the point of inflexibility, and the millions of lower and middle class New York City residents who hoped to find weekend refuge from summer heat looked like they would be shut down by a few dozen multimillionaires. But Gov. Al Smith was not happy with this arrangement. And in a speech arguing in favor of these parks and beaches, he also made some pretty profound statements about democracy: In high school, I was taught not to repeat words too often in the same paragraph, or even within a relatively short essay. I know I am not alone in having been taught that way, because many of the people I’ve mentored over the years present me drafts of their writing which show that they have been working hard to give a different name to the main topics of their writings, each time those topics occur. A person writing about congestive heart failure, for example, may call it congestive heart failure one time, CHF another time, systolic dysfunction yet another time, etc., leaving the reader to wonder whether these are different but related concepts or simply the same idea put forward in a variety of guises. But often, repetition is a mark of good writing, not only because it is easier to understand, but because repeating the same word over the course of a paragraph, or even a longer chunk of writing, can give the writing rhythm.

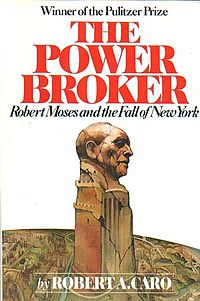

In high school, I was taught not to repeat words too often in the same paragraph, or even within a relatively short essay. I know I am not alone in having been taught that way, because many of the people I’ve mentored over the years present me drafts of their writing which show that they have been working hard to give a different name to the main topics of their writings, each time those topics occur. A person writing about congestive heart failure, for example, may call it congestive heart failure one time, CHF another time, systolic dysfunction yet another time, etc., leaving the reader to wonder whether these are different but related concepts or simply the same idea put forward in a variety of guises. But often, repetition is a mark of good writing, not only because it is easier to understand, but because repeating the same word over the course of a paragraph, or even a longer chunk of writing, can give the writing rhythm. I’m currently in the middle of reading Robert Caro’s first book, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. I’ll be blogging intermittently about this wonderful book over the next few weeks. Expect a few of those posts to be focused on drawing writing lessons from this wonderful author.

I’m currently in the middle of reading Robert Caro’s first book, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. I’ll be blogging intermittently about this wonderful book over the next few weeks. Expect a few of those posts to be focused on drawing writing lessons from this wonderful author.

Upon the death of his wife, Thomas Jefferson went into a deep depression. In crushing words, he described his state of mind to his sister-in-law, in a sentence that could be placed in psychiatric manuals next to a definition of depression:

Upon the death of his wife, Thomas Jefferson went into a deep depression. In crushing words, he described his state of mind to his sister-in-law, in a sentence that could be placed in psychiatric manuals next to a definition of depression: In his youth, Jefferson didn’t lack for confidence except, it seems, when smitten by an attractive girl. One night at a dance, he worked up a bunch of things he could say to a girl named Rebecca who he was hoping to become acquainted with: “I was prepared to say a great deal: I had dressed up in my own mind such thoughts as occurred to me, in as moving language as I knew how, and expected to have performed in a tolerably creditable manner.” Let’s face it: if anyone could impress a girl with eloquence, it would have been Jefferson. But things didn’t go so well, and here’s how Jefferson described that in a letter he wrote the next day:

In his youth, Jefferson didn’t lack for confidence except, it seems, when smitten by an attractive girl. One night at a dance, he worked up a bunch of things he could say to a girl named Rebecca who he was hoping to become acquainted with: “I was prepared to say a great deal: I had dressed up in my own mind such thoughts as occurred to me, in as moving language as I knew how, and expected to have performed in a tolerably creditable manner.” Let’s face it: if anyone could impress a girl with eloquence, it would have been Jefferson. But things didn’t go so well, and here’s how Jefferson described that in a letter he wrote the next day: