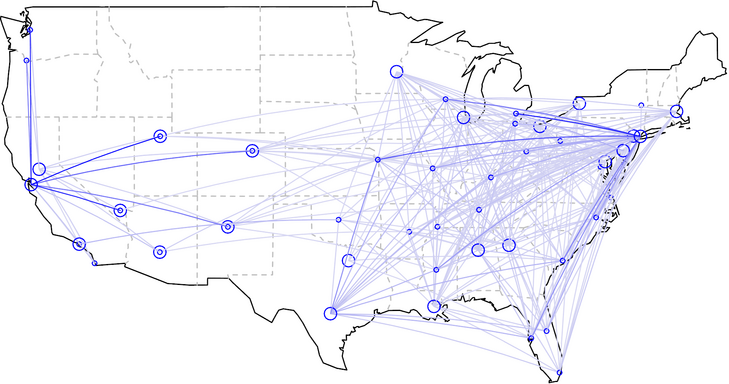

As I have described in two earlier posts, here and here, the transplant system in the US suffers from terrible geographic disparities. People needing liver transplants in Northern California wait more than six years on average for an organ to become available, versus only three months in places like Memphis Tennessee. The solution to the geographic problem seems straightforward: stop giving priority to local transplant candidates over needier candidates in other locations. And the only barrier to fixing the problem appears to be the recalcitrance of transplant centers who are benefiting from the current system. Indeed, in 1999, the Institute of Medicine called upon the transplant community to reduce geographic disparities in transplant access by sharing organs more widely. By that time, the science of organ preservation had already advanced to the point where organs like livers and kidneys could be transported successfully from New York to Tennessee and still be healthy enough to thrive after transplantation. Yet a decade and a half later, the system remains unchanged. Bruce Vladek, former director of Medicare and Medicaid, laments that “the transplant community has largely ignored the [IOM’s] recommendation.” Sharing transplantable organs would give patients a more equal chance of receiving transplants, regardless of where they live, and would also eliminate the unfair advantage patients receive when they list themselves at multiple transplant centers.

But this solution is not as straightforward as it seems. If the transplant system begins flying organs across transplant regions, those centers with the longest waiting lists, typically filled with the sickest patients, would become net importers of transportable organs. Huge programs like the University of Pennsylvania would become even bigger. And some, perhaps most, small transplant programs would go out of business, unable to compete for scarce organs when they become available. With much shorter waiting lists, the chances that one of their patients would be the top candidate for an available organ would be relatively slim, like competing in a lottery where everyone else has five times as many tickets as you do. Moreover, if small transplant programs collapse, that could doom the hospitals and medical centers housing those programs. The money the centers lose on, for instance, treating Medicaid patients with pneumonia would no longer be balanced by the money they make transplanting people with liver disease. Finally, the loss of the smaller programs could make it harder for patients in rural communities to undergo transplantation evaluations.

In trying to make our transplant system fairer, we are forced to decide whether we are willing to drive small transplant programs out of business. Indeed, questions about whether to protect small medical centers from the business of medical practice are becoming increasingly relevant across American healthcare, even beyond the boundaries of transplantation medicine. Small medical centers are under intense pressure to compete for patients, in part because they have a difficult time matching the price of high-volume centers. Consider a medical center like the Mayo Clinic. Because of its size and experience, the Clinic has become more efficient than many smaller medical centers, the result being a growth in market share, as patients fly across the country to Rochester Minnesota for their artificial hips and their pacemaker implants, their healthcare savings more than making up for the cost of the trip. Such market-share dominance is already becoming an issue in organ transplantation. Wal-Mart has contracted with the Mayo Clinic to perform transplants on any of its employees who develop organ failure. Wal-Mart even pays to house these employees near one of Mayo’s hospitals, so they can wait for organs to become available and recover from their subsequent transplant.

Contracting with the Mayo Clinic makes sense for Wal-Mart, because the company can obtain relatively low price transplants for its employees. Mayo’s size offers it efficiencies of scale not available to smaller transplant programs, and Wal-Mart’s size no doubt enabled it to negotiate discounted rates for the care its employees receive.

Large medical centers not only have efficiencies of scale, that allow them to charge lower prices, but often provide higher quality of care for complex conditions, because they gain more experience treating such conditions. Research has shown that, all else equal, experienced healthcare providers often provide better care than less experienced ones. For instance, among patients with pancreas tumors, 14% die shortly after surgical removal of the tumor at hospitals where such procedures occur one or two times per year. In hospitals where such procedures are more common, postoperative mortality is less than 4%.

Debates about organ allocation must consider this relationship between the volume and quality of healthcare. David Axelrod, a Dartmouth transplant surgeon, conducted a study of liver transplant outcomes at small and large transplant programs, comparing the smallest third of programs (which transplanted a median of 21 patients per year) to the largest third of programs (which transplanted more than 90). He found, all else equal, that patients transplanted at the smaller programs were 30% more likely to die in the first year after their transplant. “The differences were striking,” notes Axelrod, “but that does not mean all patients should head to large transplant centers, not with the way our current system is set up. After all, some of those large programs, like ones in San Francisco where Steve Jobs lived, also have long waiting times. If you have a large center with great post-transplant outcomes, but most patients die before they ever get transplanted,” he asked me, “is that the best option for the patients?”

I interpreted that as a rhetorical question. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)