The below post is a response to my article Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide by Kathryn L. Tucker, JD. My own thoughts on her response are here.

The below post is a response to my article Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide by Kathryn L. Tucker, JD. My own thoughts on her response are here.

In a Forbes.com oped, “Death With Dignity Should Not Be Equated With Physician Assisted Suicide, Duke University physician Peter Ubel writes: “I think it is wrong-headed to equate assisted suicide with the concept of a dignified death.”

Dr. Ubel’s use of the inaccurate, value-laden term “assisted suicide” to describe a terminally ill patient’s choice to shorten a dying process that the patient finds unbearable – as some journalists also wrongly do – is concerning. Words matter.

Medical, health policy and mental health professionals recognize that the term “assisted suicide” is inaccurate, biased and pejorative in this context. Increasingly, these organizations have adopted the more accurate and neutral term “aid in dying” to refer to this choice.

The nation’s largest public health association, theAmerican Public Health Association, adopted a policy supporting aid in dying, recognizing that: “the term ‘suicide’ or ‘assisted suicide’ is inappropriate when discussing the choice of a mentally competent terminally ill patient to seek medications that he or she could consume to bring about a peaceful and dignified death.” The policy emphasizes: “the importance to public health of using accurate language.” The American Medical Women’s Association has adopted similar policy, as have a number of other national medical organizations.

A growing number of states, including Oregon, Washington, Montana,Vermont and Hawaii, permit mentally competent, terminally ill patients to obtain medications they can ingest to bring about a peaceful death if their suffering becomes unbearable. The Oregon, Washington, and Vermont lawsclearly state: “Actions taken in accordance with [the Act] shall not, for any purpose, constitute suicide, assisted suicide, mercy killing or homicide, under the law.”

Terminally ill patients do not want to die but are facing an imminent death, most after long efforts to cure their illness and heroic efforts to palliate symptoms. Despite excellent pain and symptom management, some find the dying process unbearable and want to achieve a peaceful death. Patients who can choose aid in dying do not consider that they are committing “suicide,” and find the suggestion that they are deeply offensive, stigmatizing and inaccurate. Many have publicly expressed that the term is hurtful and derogatory to them and their loved ones.

“All I am asking for is to have some choice over how I die,” wrote terminally ill patient Louise Schaefer in a letter to The Sacramento Bee. “Portraying me as suicidal is disrespectful and hurtful to me and my loved ones. It adds insult to injury by dismissing all that I have already endured; the failed attempts for a cure, the progressive decline of my physical state and the anguish which has involved exhaustive reflection and contemplation leading me to this very personal and intimate decision about my own life and how I would like it to end.”

Dying patients who choose aid in dying want to live, as evidenced by the fact that more than one-third of these terminally ill patients don’t ingest the medication even after they obtain it. But they derive great comfort knowing they have that option. For those who do take the medication to achieve a peaceful death, they have been able to cross the threshold to death in a manner consistent with their values and beliefs, and consider this choice to have enabled them to exercise a final act of autonomy consistent with how they have lived their whole life.

As noted philosopher and law professor Ronald Dworkin observed in his book Life’s Dominion (Knopf 1993): “…we live our whole lives in the shadow of death…we die in the shadow of our whole lives….We worry about the effect of life’s last stage on the character of life as a whole, as we might worry about the effect of a play’s last scene or a poem’s last stanza on the entire creative work.” We ought not insult and diminish this choice by applying an inaccurate, pejorative term. Words matter.

Kathryn L. Tucker, JD, is the Director of Advocacy & Legal Affairs for the nation’s leading end-of-life advocacy, education and support organization, and teaches Law, Medicine and Ethics at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.Compassion & Choices

![]() If an antibiotic would cure your infection, your doctor would probably still warn you about the chance of sun sensitivity before prescribing the pill.

If an antibiotic would cure your infection, your doctor would probably still warn you about the chance of sun sensitivity before prescribing the pill.

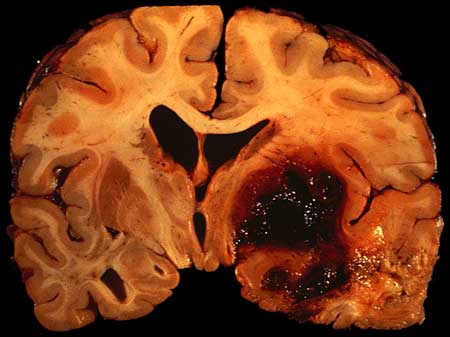

In research I have had the pleasure of conducting with Darin Zahurenic, we are starting to find concerning data about the variability in how neurologists and neurosurgeons treat people who have strokes caused by bleeding in their brains – or what doctors call intracerebral hemorrhage. Darin recently presented some of this research at a medical conference, and the media have already begun to show interest in the work. Here’s one story:

In research I have had the pleasure of conducting with Darin Zahurenic, we are starting to find concerning data about the variability in how neurologists and neurosurgeons treat people who have strokes caused by bleeding in their brains – or what doctors call intracerebral hemorrhage. Darin recently presented some of this research at a medical conference, and the media have already begun to show interest in the work. Here’s one story: When is the treatment worse than the disease? When the high costs associated with care become a financial burden for patients and in many cases prevent them from protecting their health, contends Peter Ubel, MD, a 2007 recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Investigator Award in Health Policy Research.

When is the treatment worse than the disease? When the high costs associated with care become a financial burden for patients and in many cases prevent them from protecting their health, contends Peter Ubel, MD, a 2007 recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Investigator Award in Health Policy Research. Physicians need to broach discussions about out-of-pocket costs with patients the same way they discuss a treatment’s side effects, public policy professors wrote.

Physicians need to broach discussions about out-of-pocket costs with patients the same way they discuss a treatment’s side effects, public policy professors wrote.

Healthcare markets are complex and confusing places. But one fact is simple and straightforward: all else equal, hospitals and emergency departments are a lot more expensive than outpatient clinics. Which makes it all the more bewildering that so many low income patients prefer hospitals over primary care clinics.

Healthcare markets are complex and confusing places. But one fact is simple and straightforward: all else equal, hospitals and emergency departments are a lot more expensive than outpatient clinics. Which makes it all the more bewildering that so many low income patients prefer hospitals over primary care clinics. The below post is a response to my article

The below post is a response to my article  In 2008, the state legislature of Washington passed what was called the

In 2008, the state legislature of Washington passed what was called the  Here is a

Here is a