I joined two other, much smarter, colleagues in calling for the use of behavioral economics and decision psychology to improve the design of the websites people use to purchase health insurance in the U.S. That article came out today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here is a taste:

I joined two other, much smarter, colleagues in calling for the use of behavioral economics and decision psychology to improve the design of the websites people use to purchase health insurance in the U.S. That article came out today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here is a taste:

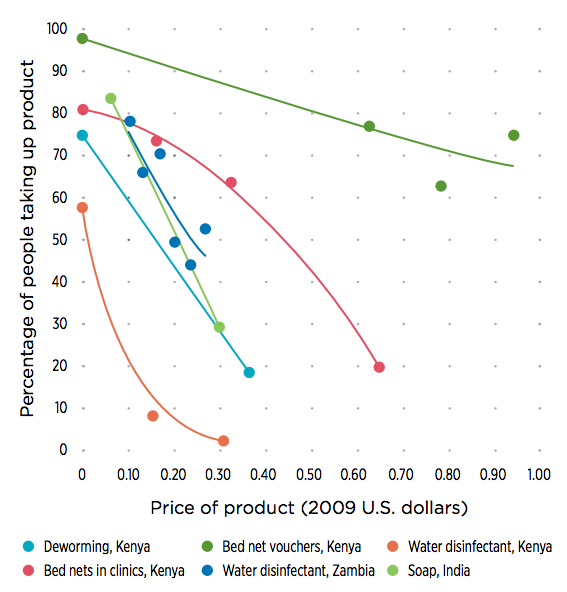

In October 2013, the Affordable Care Act introduced a new insurance market — state and federal exchanges where people can purchase health insurance for themselves or their families. Although the rollout of the exchanges was disastrous, around-the-clock efforts fixed many of the biggest technical problems, and nearly 7 million people purchased insurance in the new market. The second round of enrollment exposed some new problems with the exchange websites — for example, Colorado’s website had difficulty determining whether people were eligible for tax credits — but these problems paled in comparison with those encountered when the exchanges were first rolled out. In short, we have a largely glitch-free system of health insurance exchanges that present millions of people with a robust set of health insurance choices.

Which means that it will soon be time to tackle the much more challenging job of designing exchange websites in ways that maximize the chances that consumers will choose plans best suited to their needs and preferences. If the first round of open enrollment was primarily about avoiding catastrophe and the second round was about ironing out wrinkles in the underlying programming code, then version 3.0, in our view, should focus on redesigning the way exchanges present their insurance choices, to avoid features known to bias people’s decisions.

I have been

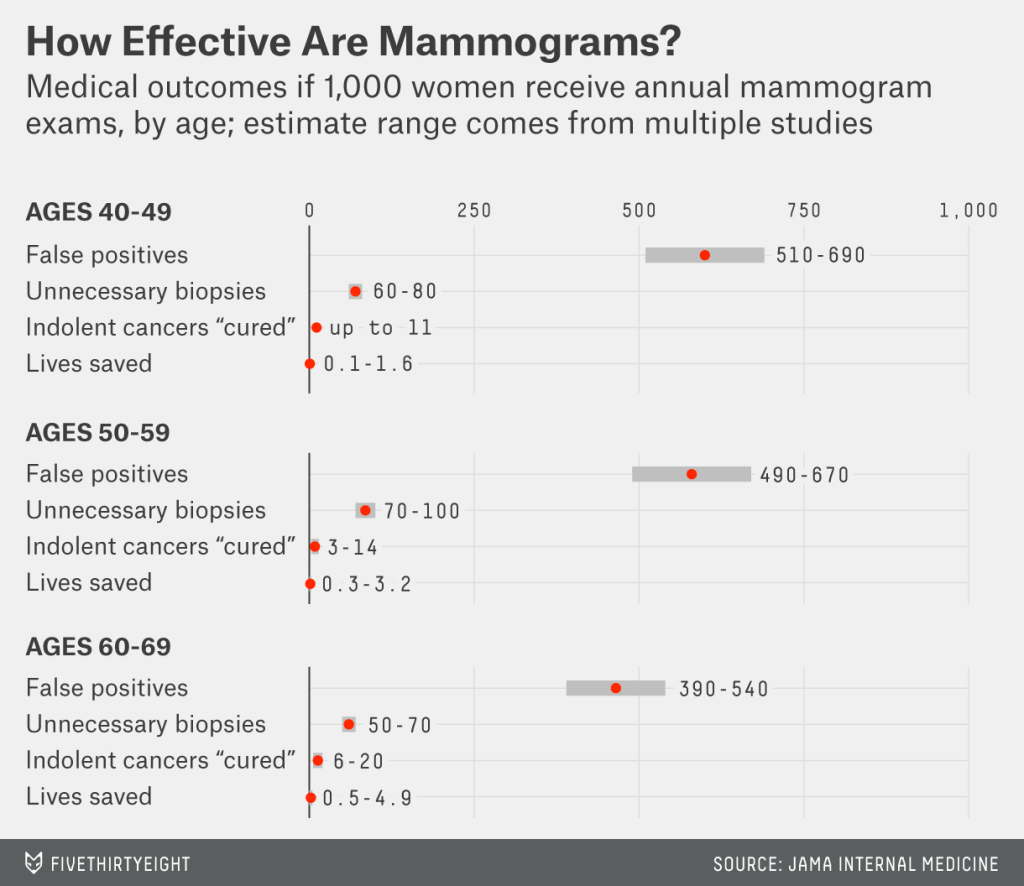

I have been  I spoke the other day to Melissa Dahl, a writer for New York Magazine. She wrote a really nice piece on what medical professionals call “contralateral prophylactic mastectomy” – when a woman with breast cancer chooses not only to remove the affected breast, but also the unaffected breast in order to reduce the chance of a subsequent cancer. There’s no evidence that this practice reduces breast cancer related mortality. And yet the practice is growing. Here is the beginning of her wonderful essay:

I spoke the other day to Melissa Dahl, a writer for New York Magazine. She wrote a really nice piece on what medical professionals call “contralateral prophylactic mastectomy” – when a woman with breast cancer chooses not only to remove the affected breast, but also the unaffected breast in order to reduce the chance of a subsequent cancer. There’s no evidence that this practice reduces breast cancer related mortality. And yet the practice is growing. Here is the beginning of her wonderful essay: A very disturbing new study was just published, in which physicians viewed a video of a patient with back pain asking for OxyContin. Twenty percent of docs said they would prescribe that med under that circumstance:

A very disturbing new study was just published, in which physicians viewed a video of a patient with back pain asking for OxyContin. Twenty percent of docs said they would prescribe that med under that circumstance: This summer I had the pleasure of speaking with a very intelligent journalist, who was working on an article about overtreatment in medical care. That article has just come out, and I thought I would give you a sample of it here:

This summer I had the pleasure of speaking with a very intelligent journalist, who was working on an article about overtreatment in medical care. That article has just come out, and I thought I would give you a sample of it here: