The oncologist had prescribed Xgeva hoping it would strengthen her bones while also delaying the progression of Angela Kahn’s breast cancer. But Kahn (a pseudonym) couldn’t get over the price of the drug. Before the oncologist had a chance to ask how she was feeling, she blurted out that the medication cost “$15,000 a shot.” “That’s crazy,” the oncologist replied, continuing by saying the price “fits right in with the rest of the insanity” of U.S. healthcare pricing. At that price, Kahn concluded, “I don’t think I should get it.”

The oncologist assured her “You’re getting it,” and they both laughed.

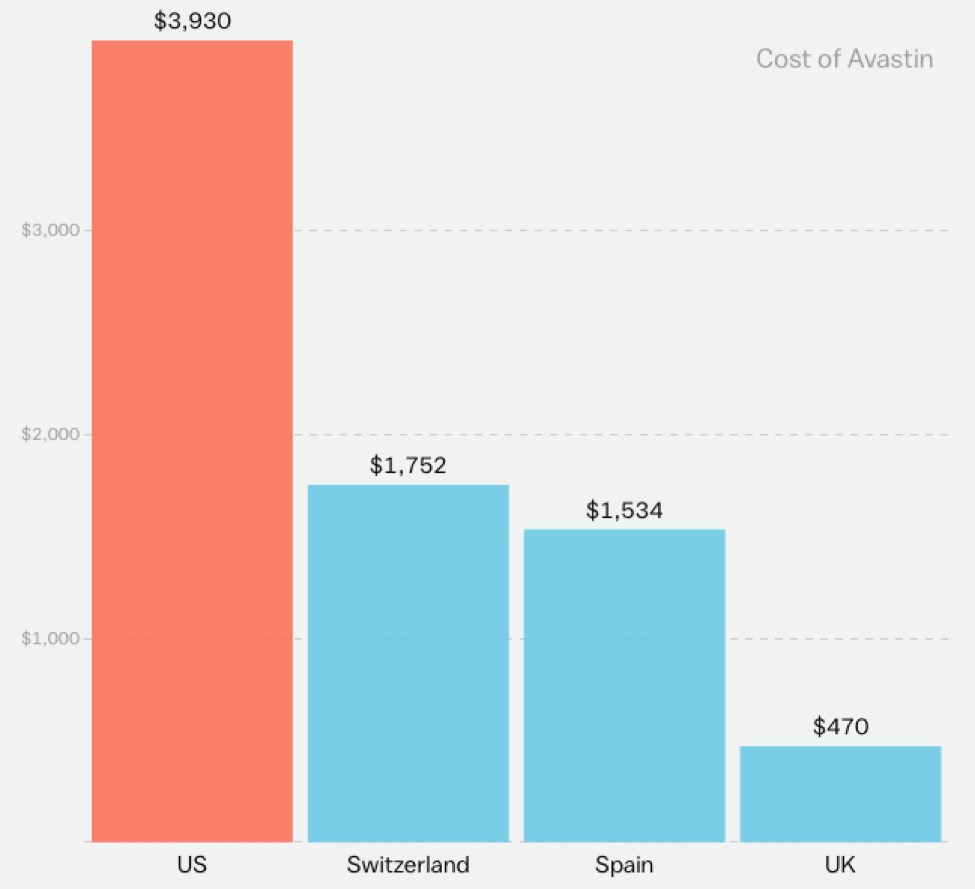

Not that either thought Xgeva’s price was a laughing matter. In fact, like many medications, Xgeva costs much more in the U.S. than in any other developed countries, with a single injection costing more than $2,000.

There’s too many reasons for these high prices to delve into them in the space of a short essay. Instead, I want to show how the insanity of American healthcare prices played out in this one, real oncology appointment. (Note: The appointment was recorded by a marketing company, Verilogue Inc., with the permission of the doctor and patient. I gained access to an anonymized transcript of the appointment for a research project approved by the Duke University IRB.)

After assuring Kahn that she’d remain on the Xgeva, her oncologist explained how he believes healthcare pricing plays out in the U.S. “It’s totally outrageous. What usually happens is the hospital or the clinic will charge 300 times what they think they can get, and the insurance company pays 1/20th of the original.”

“Oh, okay,” Kahn replied, with a touch of confusion.

“So it’s just a game, it’s a total horrible game,” the oncologist continued. “That’s crazy,” Kahn reiterated.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)