Thanks again to the Kaiser Family Foundation for keeping all of us informed about important healthcare statistics. Here’s a relatively recent snapshot of how the percent of Americans lacking health insurance has fluctuated since the 1970s. The effect of Obamacare on the statistic is undeniable:

Talking To Your Doctor About Out-Of-Pocket Costs Can Save You Money

Healthcare is often really costly. And with increasing frequency, a significant chunk of those costs is being passed on to patients in the form of high deductibles, copays, or other out-of-pocket expenses. As a result, millions of Americans struggle to pay medical bills each year.

What’s a poor patient to do?

For starters–they can talk to their doctors about these costs. According to a study my colleagues and I just published, when healthcare costs come up for discussion during clinical appointments, doctors and patients increasingly discuss strategies for how to lower out-of-pocket expenditures.

In the study, we analyzed transcripts of almost 2,000 outpatient clinical appointments, appointments audio recorded and transcribed by Verilogue Inc., a marketing research firm whose CEO, Jamison Barnett, was generous enough to collaborate with us on this research. (Full disclosure: All the doctors and patients gave permission to be audio recorded by the company. Verilogue removed all identifying information from the transcripts. And my colleagues and I did not enter into any financial relationship with the company, nor cede any control over our right to publish our findings.)

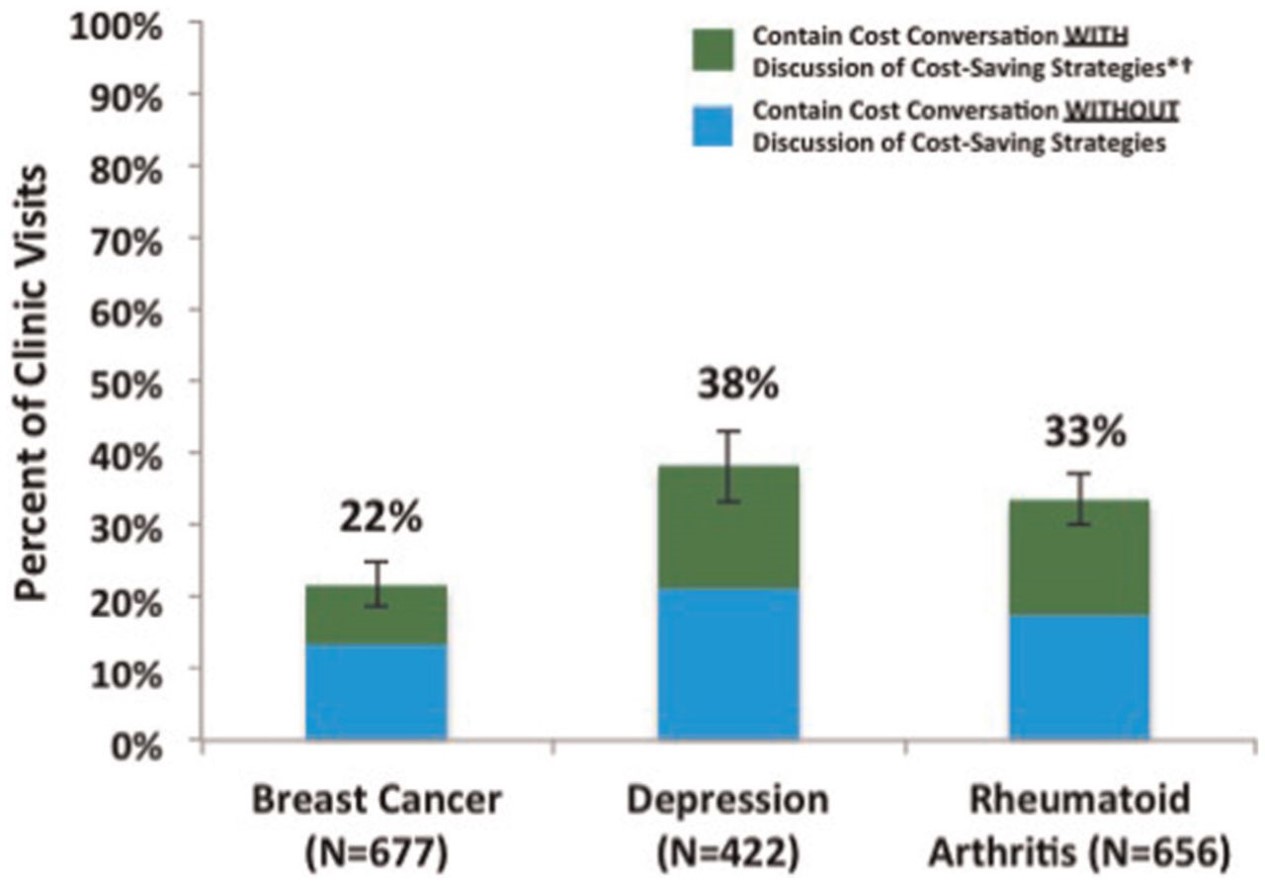

We analyzed three groups of patients, all of whom potentially face high out-of-pocket costs: breast cancer patients seeing their oncologists; rheumatoid arthritis patients seeing their rheumatologists; and patients with depression seeing their psychiatrists. We looked for any conversation that touched on the topic of healthcare costs–from discussions of whether insurance would “cover” a specific service (or whether the patient would instead be responsible for its cost) to patient complaints about out-of-pocket costs they’d already incurred from services ordered by their doctors during previous appointments.

In the first article published from these analyses (recently released on the website of Medical Decision Making), we focused on the strategies doctors and patients discuss to reduce patient out-of-pocket costs. And what did we find? That discussion of cost-reducing strategies was both common and rare. Common, in that once healthcare costs came up in the conversation, discussion of cost-reducing strategies occurred almost 40% of the time. Rare, in that healthcare costs came up as a topic of conversation in only 22-38% of the out-patient visits, meaning that in the majority of encounters, there was no discussion of healthcare costs, and thus no discussion of how to reduce patients’ out-of-pocket expenditures. Here is a picture showing those findings:

Sometimes doctors and patients found ways to reduce out-of-pocket costs without changing the plan of care. For example, doctors would refer patients to copay assistance programs, or give them free medication samples. Sometimes they would play around with the logistics of care, moving an expensive test up to December rather than January, so that the patient would not have to start spending through her deductible again.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Should Presidential Candidates Be Vilifying Physicians For The High Cost Of Medical Care?

When asked what enemies she was proud to have made during her political career, Hillary Clinton mentioned, in order, “the NRA, the health insurance companies, the drug companies [and] the Iranians.” Pretty villainous company to place healthcare industries into. But Clinton is not alone among presidential candidates in vilifying pharmaceutical and insurance industries for, as Bernie Sanders puts it, “ripping off the people.” Donald Trump called pharmaceutical profiteering “disgusting” and claimed that “insurance companies are making a fortune because they have control of the politicians.” Marco Rubio blamed high drug prices as “pure profiteering” by pharmaceutical companies. It is a strange world when Republicans join Democrats in vilifying people and companies who pursue profits through the marketplace.

Even stranger, neither party is taking aim at a group of people in the healthcare industry who have been making a fortune by exerting enormous influence over healthcare spending. No one seems to be vilifying physicians.

Yet if candidates are looking to blame someone for high healthcare costs in the United States, they should include physicians, whose decisions–to order tests or treatments–are responsible for the bulk of healthcare spending. Yes, pharmaceutical companies are charging exorbitant prices for many of their products. But patients do not receive expensive medications unless physicians prescribe them. True, insurance premiums are very expensive and rising rapidly. But those premiums reflect the cost of paying for all those services that physicians order for their patients. And some of those services reflect physician fees, which for some subspecialists are quite high. Many American physicians are extremely well paid for their work, with the median allergy doctor making almost $300,000 a year, and the median gastroenterologist making almost $400,000. Indeed, American physicians often take home 50 to 100% higher annual incomes than their peers in Europe or Canada.

So why aren’t politicians vilifying physicians? Because when they turn their attention to the role of physicians in driving up healthcare costs, candidates shift from blaming people to blaming the system. When laying out her healthcare plans, for example, Clinton remarks that “we need to shift away from the fee-for-service payment system that rewards providers who prescribe excessive tests and unnecessary procedures.” Jeb Bush also criticizes the reimbursement system, complaining that “providers are not being held directly accountable to patients for the value of the care they deliver.”

When pharmaceutical and insurance companies drive up healthcare costs, they are villainous. When physicians drive up costs–it is the system that is to blame!

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

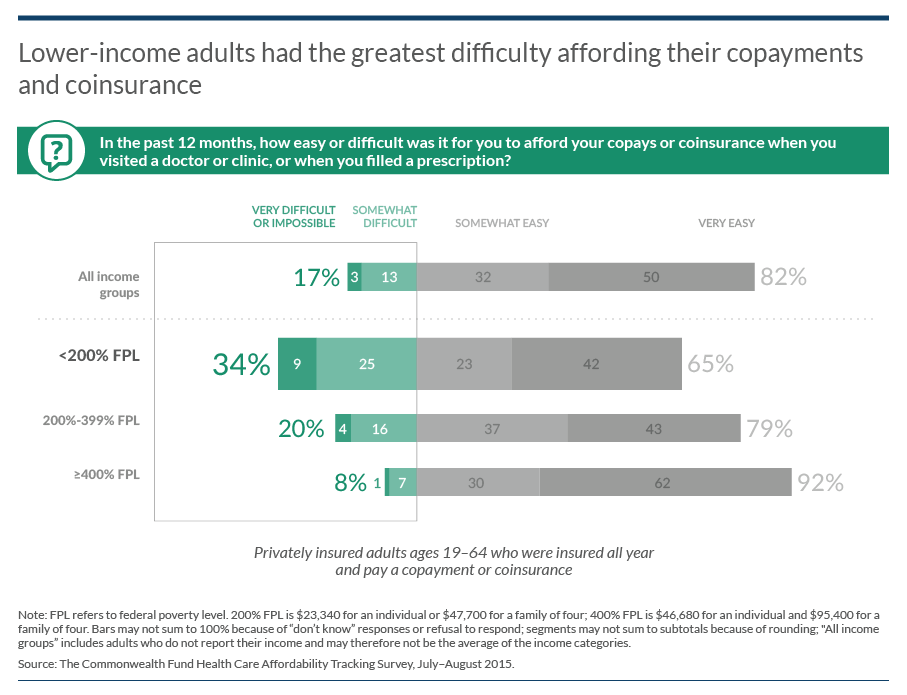

Stingy Insurance + Low Income = Bad Combination

The Commonwealth Fund recently circulated information on the widespread difficulty many Americans have paying for their medical care, even when they have insurance. Burdened by high co-pays and high coinsurance rates, these out-of-pocket expenses are putting people on the financial edge. Here is a picture of the results, which show that a third of people living at less than 200% of the federal poverty limit struggled paying for such services in the past 12 months:

We have an affordability problem in the US healthcare system!

We have an affordability problem in the US healthcare system!

Judging Policies by Their Supporters

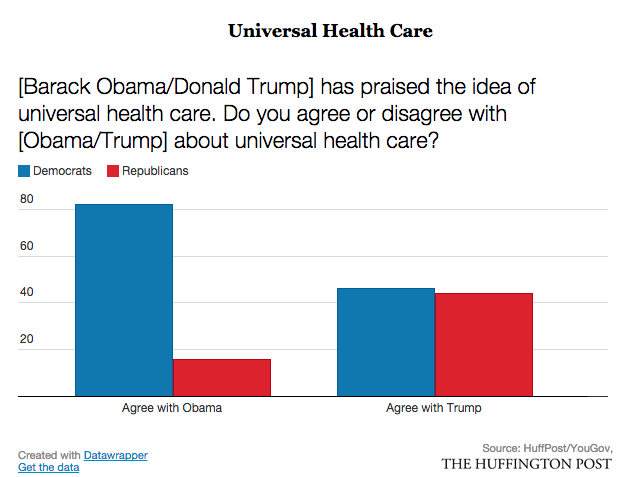

The world is complicated. It’s hard to know what the federal government should do about a whole range of problems. That’s why most people take a shortcut, and judge policies based on their opinion of the people who support or oppose those policies. If you like someone, and he supports a policy, then you are more likely to think the policy is a good idea.

Take this clever, if not totally surprising, poll reported on in the Huffington Post – which showed dramatic changes in support for universal healthcare depending on whether people thought Barack Obama or Donald Trump supported the idea:

As with much of partisan politics, there’s no political party immune to these strange patterns of belief. God bless America!

As with much of partisan politics, there’s no political party immune to these strange patterns of belief. God bless America!

Are Device Manufacturers Playing Bait-And-Switch with the FDA?

The problem with the FDA is that if often requires so much proof of safety and effectiveness that the time it takes to bring a new product to market can grow by 3, 4, or even more years. FDA delays into the time that companies have to exclusively produce and sell their products.

In recognition of this problem, the FDA sometimes grants marketing approval to innovative new devices through a Pre-Market Approval Pathway, or PMA. Under this pathway, companies are allowed to bring their products to market more quickly – with less than optimal evidence on safety and effectiveness – as long as they promise to continue collecting such data through post-market surveillance.

According to a study in JAMA, device manufacturers often fail to keep up their side of this bargain.

In the study, Vinay Rathi and colleagues looked at all 28 new high risk devices receiving PMA approval in 2010 and 2011. They found that FDA approval was often based on scant data – studies of less than 300 patients with no blinding and limited follow-up. (With blinding, clinicians measuring patient outcomes do so unaware of which patients have received which interventions. Without blinding, such outcome measures can be biased by clinicians’ expectations.)

Given the small number of patients studied prior to market approval, it is that much more important that manufacturers continue to collect data once their products come to market. Unfortunately, most devices are not well studied once on the market. According to authors of the JAMA study: “Most devices have been or will be evaluated through only a few studies, which often focus on surrogate markers of disease in small numbers of patients followed up over short periods of time.” In fact, almost half of post-market studies are funded without support from the manufacturer.

Why are manufacturers being so lax in conducting post-market research?

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

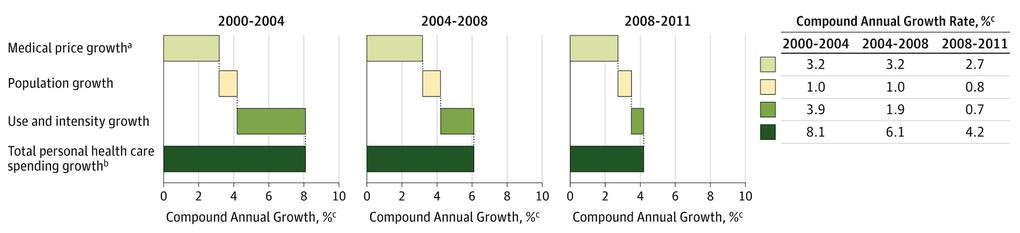

Houston (and the Rest of the US Healthcare System): We Have a Price Problem

Want to know why we spent so much on healthcare in United States? There are lots of reasons. Our population is aging, the rate of diabetes is rising, and the healthcare industry keeps developing wonderful but expensive new technologies to treat our ailments. But more than anything, we have a price problem. It’s price increases that account for the majority of growth in healthcare spending. Here’s a figure from an article in JAMA, showing these trends from 2000 through 2011:

Paying for "Patient Satisfaction" Harms Hospitals That Care for Poor People

All else equal, it would be wonderful if hospitals had an incentive to provide high quality care. It does not seem fair to pay the same amount of money to a hospital that does a great job of caring for its pneumonia patients and one that does a lousy job. For the most part, however, third party payers like insurance companies and Medicare pay hospitals for the volume of services they provide, or volume of patients they treat, not for the quality of the care they provide.

All else equal, it would be wonderful if hospitals had an incentive to provide high quality care. It does not seem fair to pay the same amount of money to a hospital that does a great job of caring for its pneumonia patients and one that does a lousy job. For the most part, however, third party payers like insurance companies and Medicare pay hospitals for the volume of services they provide, or volume of patients they treat, not for the quality of the care they provide.

Inattention to quality is coming to an end. Hospitals are increasingly being paid in part for their performance. For example, in 2013 Medicare began a value-based purchasing program, or VBP. Under the program, Medicare withholds a percentage of payments throughout the year and then redistributes those dollars to hospitals that achieve the highest scores on a range of quality measures. In the first year of the program, this redistribution amounted to about $1 billion.

In theory, pay-for-performance makes a great deal of sense. But in practice, pay-for-performance is only as good as the quality measures used to determine performance. And Medicare’s measures, by placing significant weight on patient satisfaction scores, are hurting hospitals that disproportionately care for low income populations.

Let’s take a closer look at Medicare’s quality measures. Some are what healthcare experts call process measures, which identify whether hospitals do the right things at the right times to the right patients. When patients are admitted with heart attacks, for example, a process measure might assess how many of those patients receive aspirin and beta blockers upon discharge, or how many receive revascularization efforts in the cath lab within 30 minutes of arrival.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Cancer Drugs Aren't As Cost-Effective As They Used To Be

Cancer drugs have become increasingly expensive in recent years. No one blinks anymore when a new lung cancer or colon cancer treatment comes to market priced at more than $100,000 per patient. In part, we don’t blink because we have simply gotten used to such prices – the shock has worn off. Moreover, many of these new treatments are targeted therapies that only work for patients whose cancers express specific mutations, targeting the specific genetics underlying their neoplasms. Because these treatments are targeted, we know that only a subset of patients will receive them, thereby limiting the overall cost of the therapies. We are willing to give pharmaceutical companies some leeway in pricing these drugs, because we recognize that such targeted therapies limit the pool of patients pharmaceutical companies can count on to recoup their investments. In fact, due to such precision targeting, we even hope that the new treatments will be so much more effective against cancers they will justify their high prices.

Unfortunately, a study by David H. Howard and colleagues shows that new cancer treatments, on average, are less cost-effective than older ones. The price of cancer drugs is rising faster than the effectiveness.

In the simplest terms, cost-effectiveness quantifies the ratio between how much an intervention raises healthcare costs and how much it improves health outcomes. For advanced cancers, one important outcome is whether the treatment increases patient survival. A $100,000 treatment that increases life expectancy by an average of, say, six months would have a cost-effectiveness of around $200,000 per life year. (The actual cost effectiveness could differ, depending on how the drug influences other healthcare costs.) That $200,000 per life year cost-effectiveness ratio is on the border of what health policy experts think is worth spending for a year of life. And if that extra year of life is of low quality, the intervention would be deemed even less cost-effective.

(To read the rest of the article, please visit Forbes.)

Merger Mania in Medicine — What Will It Cost Us?

The federal government is currently debating whether the big six health insurance companies in the U.S. will soon become the big four. Aetna and Humana have announced plans to merge, as have Anthem and Cigna. The American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association strongly oppose the mergers, saying they will reduce competition in consumer markets.

Meanwhile, healthcare provider groups continue to consolidate. Small hospitals either get swallowed up by larger ones or risk going out of business. The federal government even seems to be encouraging provider consolidation, by establishing incentives for them to form accountable care organizations, or ACOs.

The short answer is: no one knows, because so much depends on the relative power of payers and providers in individual markets.

If consolidation was limited to providers, prices would rise (absent government intervention). For example, prices for total knee replacements have been shown to be higher in markets where orthopedic surgeons have bonded together in larger organizations. This is the finding of a study led by Eric Sun from Stanford University. Sun collected information on physician fees for this procedure, from a database of health insurance claims. He also figured out how competitive orthopedic markets are in different parts of the country. In some markets, patients can choose from a wide range of independent orthopedic surgeons. In more concentrated markets, their choices will be more limited, due to the existence of large orthopedic groups that account for a high proportion of local services. Patients in those more concentrated markets will face, on average, a $200 increase in the fee their surgeons charge for such services.

The price of healthcare in the U.S. is determined in part by negotiations between payers and providers. When a large group of orthopedic surgeons commands a significant percent of business in a given area, they are in a good position to bargain for higher fees from local insurers.

What happens, then, when insurers gain market share? (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)