In high school, I was taught not to repeat words too often in the same paragraph, or even within a relatively short essay. I know I am not alone in having been taught that way, because many of the people I’ve mentored over the years present me drafts of their writing which show that they have been working hard to give a different name to the main topics of their writings, each time those topics occur. A person writing about congestive heart failure, for example, may call it congestive heart failure one time, CHF another time, systolic dysfunction yet another time, etc., leaving the reader to wonder whether these are different but related concepts or simply the same idea put forward in a variety of guises. But often, repetition is a mark of good writing, not only because it is easier to understand, but because repeating the same word over the course of a paragraph, or even a longer chunk of writing, can give the writing rhythm.

In high school, I was taught not to repeat words too often in the same paragraph, or even within a relatively short essay. I know I am not alone in having been taught that way, because many of the people I’ve mentored over the years present me drafts of their writing which show that they have been working hard to give a different name to the main topics of their writings, each time those topics occur. A person writing about congestive heart failure, for example, may call it congestive heart failure one time, CHF another time, systolic dysfunction yet another time, etc., leaving the reader to wonder whether these are different but related concepts or simply the same idea put forward in a variety of guises. But often, repetition is a mark of good writing, not only because it is easier to understand, but because repeating the same word over the course of a paragraph, or even a longer chunk of writing, can give the writing rhythm.

Consider this paragraph from The Power Broker, by Robert Caro. In the paragraph he is writing about the main character of the book, Robert Moses – a behind the scenes politician, to most eyes, who nevertheless had an enormous impact on New York State and New York City, from its highways and parks to many other aspects of urban design. Moses had a brilliant legal mind, and was famous for throwing language into obscure sections of bills that would sneakily enable him, in whatever government position he held at the time, to garner more power.

Quoted below, Caro writes about the way he slipped concepts of “entry and appropriation” into the law in a way that clearly circumvented what anyone else wanted the law to accomplish, thereby accomplishing exactly what Moses wanted to:

To realize a dream of unprecedented scope, Robert Moses, by use of the law, had armed himself with unprecedented powers – and then, finding that these powers were still inadequate, he had deliberately gone beyond them, beyond the law. “Entry and appropriation” was, even as defined in law, of questionable constitutionality in its negation of the individual’s rights when his property was coveted by the state. And Moses had gone beyond the definition to use the power of the state with even less restraint than the law allowed. But both courts and Legislature understood the situation; before both courts and Legislature, Moses stood stripped of all defenses and, it seemed in February 1925, both courts and Legislature would now step in and rectify the situation, the courts by affording redress to the individuals injured by his actions, the Legislature by ensuring that he never again have the opportunity similarly to injure any other individual.

But the ultimate court in which the fate of Moses and his dream was to be resolved would be the court of public opinion. And in this court, Robert Moses had close to hand three formidable weapons…

Like a drumbeat, the words courts and Legislature recur throughout the paragraphs. And the closely related concepts of law and court do too. But rather than make the writing boring and repetitive, they propel the writing along. Beautiful stuff. Expect to see more over the next few weeks.

(Click here to view comments)

I have long been a fan of single sentence paragraphs.

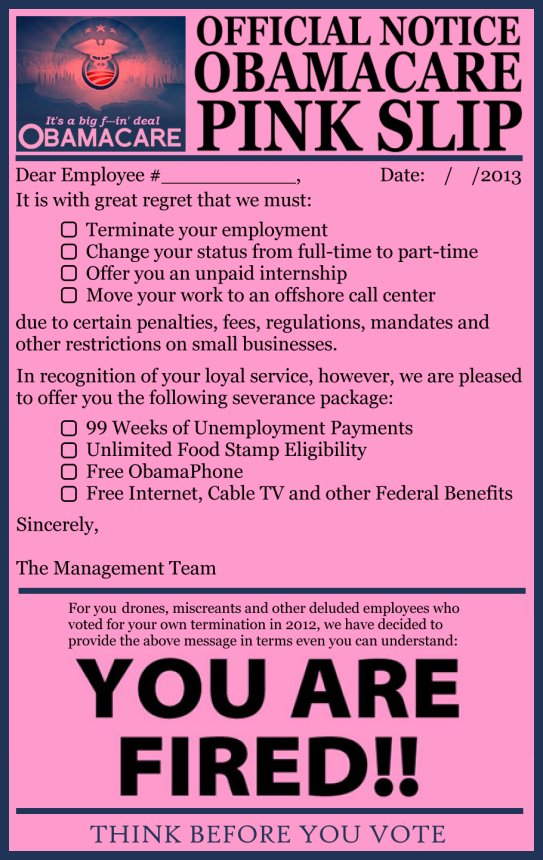

I have long been a fan of single sentence paragraphs. Imagine you are a small business owner deciding whether to hire two new employees, your 50th and 51st workers respectively. Would you hire them knowing that, by surpassing the magic number 50, you will now be obligated under Obamacare to pay a penalty unless you offer all your employees affordable healthcare insurance?

Imagine you are a small business owner deciding whether to hire two new employees, your 50th and 51st workers respectively. Would you hire them knowing that, by surpassing the magic number 50, you will now be obligated under Obamacare to pay a penalty unless you offer all your employees affordable healthcare insurance?

Jennifer spends lots of time with dead things, dead humans actually. She works in a pathology lab. One night, she is asked to incinerate a fresh human cadaver, and she is struck that it would be a waste to throw away perfectly good meat. So, even though she is against killing and is a vegetarian for moral reasons, she cuts a chunk of flesh off the cadaver, takes it home, and has it for dinner.

Jennifer spends lots of time with dead things, dead humans actually. She works in a pathology lab. One night, she is asked to incinerate a fresh human cadaver, and she is struck that it would be a waste to throw away perfectly good meat. So, even though she is against killing and is a vegetarian for moral reasons, she cuts a chunk of flesh off the cadaver, takes it home, and has it for dinner. In 1925, a handful of extremely wealthy Long Island residents tried to thwart state plans to run highways from New York City through Long Island to beaches that the masses could enjoy. These wealthy people were understandably upset, that part of their property would be taken away to make room for highways and the like. But they resisted to the point of inflexibility, and the millions of lower and middle class New York City residents who hoped to find weekend refuge from summer heat looked like they would be shut down by a few dozen multimillionaires. But Gov. Al Smith was not happy with this arrangement. And in a speech arguing in favor of these parks and beaches, he also made some pretty profound statements about democracy:

In 1925, a handful of extremely wealthy Long Island residents tried to thwart state plans to run highways from New York City through Long Island to beaches that the masses could enjoy. These wealthy people were understandably upset, that part of their property would be taken away to make room for highways and the like. But they resisted to the point of inflexibility, and the millions of lower and middle class New York City residents who hoped to find weekend refuge from summer heat looked like they would be shut down by a few dozen multimillionaires. But Gov. Al Smith was not happy with this arrangement. And in a speech arguing in favor of these parks and beaches, he also made some pretty profound statements about democracy:

In high school, I was taught not to repeat words too often in the same paragraph, or even within a relatively short essay. I know I am not alone in having been taught that way, because many of the people I’ve mentored over the years present me drafts of their writing which show that they have been working hard to give a different name to the main topics of their writings, each time those topics occur. A person writing about congestive heart failure, for example, may call it congestive heart failure one time, CHF another time, systolic dysfunction yet another time, etc., leaving the reader to wonder whether these are different but related concepts or simply the same idea put forward in a variety of guises. But often, repetition is a mark of good writing, not only because it is easier to understand, but because repeating the same word over the course of a paragraph, or even a longer chunk of writing, can give the writing rhythm.

In high school, I was taught not to repeat words too often in the same paragraph, or even within a relatively short essay. I know I am not alone in having been taught that way, because many of the people I’ve mentored over the years present me drafts of their writing which show that they have been working hard to give a different name to the main topics of their writings, each time those topics occur. A person writing about congestive heart failure, for example, may call it congestive heart failure one time, CHF another time, systolic dysfunction yet another time, etc., leaving the reader to wonder whether these are different but related concepts or simply the same idea put forward in a variety of guises. But often, repetition is a mark of good writing, not only because it is easier to understand, but because repeating the same word over the course of a paragraph, or even a longer chunk of writing, can give the writing rhythm. I’m currently in the middle of reading Robert Caro’s first book, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. I’ll be blogging intermittently about this wonderful book over the next few weeks. Expect a few of those posts to be focused on drawing writing lessons from this wonderful author.

I’m currently in the middle of reading Robert Caro’s first book, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. I’ll be blogging intermittently about this wonderful book over the next few weeks. Expect a few of those posts to be focused on drawing writing lessons from this wonderful author.