Are there really too few primary care physicians? And if so, what can we do to solve the PCP shortage? The standard answer to the first question is “yes, we have too few PCPs.” And the standard solution is to train more such docs, or allow more foreign-trained primary care docs into the country or, better yet, simply pay PCPs more money, so that graduating medical students will be more likely to pursue such careers.

Are there really too few primary care physicians? And if so, what can we do to solve the PCP shortage? The standard answer to the first question is “yes, we have too few PCPs.” And the standard solution is to train more such docs, or allow more foreign-trained primary care docs into the country or, better yet, simply pay PCPs more money, so that graduating medical students will be more likely to pursue such careers.

I have a different set of answers. To the first question, of whether we have a PCP shortage, my answer is: “Maybe yes, but very possibly no.”

Keep in mind, before you rush to judge my answer, that I am a proud primary care physician, trained in general internal medicine. Coming out of residency, I was happy to achieve lower pay than my subspecialty colleagues in order to experience the pleasures of taking care of “the whole patient”…(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Do We Have a Drug Problem in the US?

Since the recession hit hard a few years ago, health care expenditures have slowed dramatically. It now looks like, at least for medications, cost increases are making a comeback. For instance:

Since the recession hit hard a few years ago, health care expenditures have slowed dramatically. It now looks like, at least for medications, cost increases are making a comeback. For instance:

Nexium, a heartburn drug, had a 7.8% price hike to a $262 average prescription in the first nine months of 2012.

Enough to make your stomach hurt, yes?

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, medication prices rose 3.6% in 2012, twice the 1.7% inflation rate. One year does not a trend make. And the pharmaceutical industry is under a ton of pressure. Many of their best selling products have gone, or soon will go, generic. Even Nexium, which isn’t generic, faces stiff competition from generics that are just as effective for most people. That said, it is a good idea to find out how much your pills cost before you take them and, more importantly, find out if there are more affordable alternatives.

(Click here to view comments)

Can States Afford to Take Federal Medicaid Dollars?

States face a tough choice right now, of whether to expand their Medicaid roles with 90% of the costs being borne by the government. (Medicaid is a combined Federal/State program to pay for healthcare of low income individuals and families.) Why is taking money from the Feds a tough decision?

States face a tough choice right now, of whether to expand their Medicaid roles with 90% of the costs being borne by the government. (Medicaid is a combined Federal/State program to pay for healthcare of low income individuals and families.) Why is taking money from the Feds a tough decision?

For starters, it means supporting, gulp, “Obamacare”. Republican governors who expand Medicaid, in accord with that law, will look like they are supporting that guy who so many of their supporters believe is a Kenyan socialist.

To make matters more complicated, many business interests (especially hospitals) are urging Republicans to support Medicaid expansion. Without this expansion, they know they will have fewer paying customers.

Politics and business aside, one other fact makes this a tough call: Even 10% of an expensive expansion is a lot of money. Here is an excerpt from a recent USA Today article, explaining the dilemma:

Though states could reap a large return from expanded Medicaid benefits, the extra costs are a challenge, said Michael Morrissey, a University of Alabama health care economist.

A recent study by Morrissey found that Medicaid expansion in Alabama would generate almost $20 billion in new income from 2014 to 2020 and $1.7 billion in extra taxes to local government. That assumed that 60% of the uninsured would get insurance. To get those benefits, Alabama taxpayers would have to come up with $771 million in new revenue to pay to administer the expansion, he said.

What do you think? Can States afford this? Should they find a way to afford this? Is it time, as I’ve urged before, to nationalize Medicaid?

(Click here to view comments)

Price Transparency at its WORST

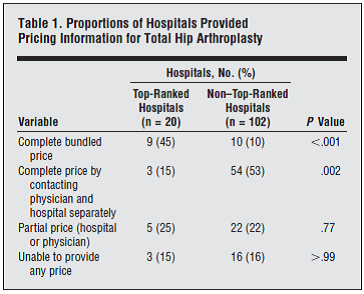

You may have heard this week about a new study, led by my friend and colleague Pete Cram, which revealed astonishing variation in prices for hip replacement surgery. Staggering, actually—ranging from a bit over $10,000 to over $125,000. I have blogged a bit about hospital prices, and doctor fees, even a recent post on orthopedic surgery costs in the US. Now these prices are crazy. And to be fair to the hospitals, these were prices for uninsured patients. And frankly: not many uninsured patients pay for hip replacements.

But some people do not have health insurance. And when that happens, they need to be able to shop for care. And that, in my view, raises the even more troubling aspect of this study. Cram and his colleagues discovered that it was really damn hard for patients (in this case, someone making phone calls asking about this operation) to get price estimates. Look at this table, from the paper:

What Iraq and Cuba Had in Common

Interesting take on the Bay of Pigs thinking in the Kennedy administration, as summarized in Jim Newton’s book on the Eisenhower Presidency:

Interesting take on the Bay of Pigs thinking in the Kennedy administration, as summarized in Jim Newton’s book on the Eisenhower Presidency:

“The entire enterprise depended on an intelligence assumption that proved false, namely, that the Cuban people would greet the invasion force as liberators and turn against Castro.”

Do U.S. Physicians Make Too Much Money?

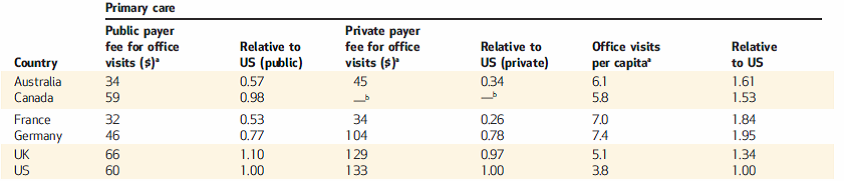

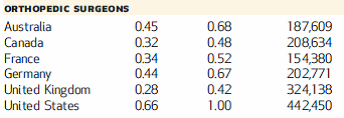

In September of 2011, Laugesen and colleagues looked at why health care in the US costs so much. Part of their analysis explored primary care physician fees. It showed that primary care docs in the US make a bit more, per office visit, than their colleagues in 5 other countries. But Americans are much less likely to have an appointment with their primary care doctors.

Laugesen also looked at orthopedic surgery in the 5 countries. Once again, the cost of American health care can NOT be blamed on the volume of procedures we do here. Instead, it is the amount of money we charge for those procedures!

Do Oncologists Lie to Their Patients About Their Prognoses?

Andrews was easily the most anxious patient I took care of that month, a gray Michigan February (is there any other kind?) which I spent in the hospital caring for patients admitted to the general medical ward at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center. (Andrews is a pseudonym, as are all the patients I blog about, unless otherwise indicated.) He had plenty to be anxious about, too. His leukemia was raging out of control, his blood looking like pus, teeming as it was with malignant white blood cells. At his age—he was almost 60—and after a decade of chronic bone marrow cancer, his disease was especially dangerous. Odds were high he would survive for less than a year.

Andrews was easily the most anxious patient I took care of that month, a gray Michigan February (is there any other kind?) which I spent in the hospital caring for patients admitted to the general medical ward at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center. (Andrews is a pseudonym, as are all the patients I blog about, unless otherwise indicated.) He had plenty to be anxious about, too. His leukemia was raging out of control, his blood looking like pus, teeming as it was with malignant white blood cells. At his age—he was almost 60—and after a decade of chronic bone marrow cancer, his disease was especially dangerous. Odds were high he would survive for less than a year.

Unless . . . ! Unless the genetics of his cancer were favorable, indicating a good likelihood that he would respond to chemotherapy. So Andrews and I (and the rest of my general medicine team) waited to hear back from the oncologists about the result of his genetic studies.

Andrews wasn’t afraid of dying, because he’d already had a first-hand view of death at its worst. Twenty years earlier, he was working as a card dealer in Vegas and had fallen in love with another dealer. In the open-minded culture of that city… (Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Review of Critical Decisions

“Revolutions are often fought over dichotomies—the king versus the people, the bourgeoisie versus the proletariat, and, of course, the autonomous patient versus the paternalistic doctor.” So observes Peter Ubel in the conclusion of Critical Decisions: How You and Your Doctor Can Make the Right Medical Choices Together.

“Revolutions are often fought over dichotomies—the king versus the people, the bourgeoisie versus the proletariat, and, of course, the autonomous patient versus the paternalistic doctor.” So observes Peter Ubel in the conclusion of Critical Decisions: How You and Your Doctor Can Make the Right Medical Choices Together.

Who decides? Doctor or patient? For decades, too many of the advocates who have tangled with the establishment to empower patients have acted as though there is only black and white. The patient decides, not the doctor. The result has been a toxic standoff.

By throwing the dichotomy under the bus, Ubel takes a crucial step forward. Patients and doctors must work together to get to the right decision. The much tougher questions follow: How? What are the rules of engagement? How should the interaction proceed? Who does what?

Ubel’s expert dissection of the hidden complexities of these questions is thorough and impressive. In addition, Ubel is quite evidently a gifted writer,thinker, and communicator. Critical Decisions is a first-rate effort to popularize the science of medical decision making. Some readers will devour this book;in fact, researchers in the medical decision-making community might finish itin a single sitting. And general readers with an intellectual interest in healthcare—those who eagerly anticipate Atul Gawande’s next New Yorker article…(Read more at Health Affairs)

Two Pictures Summarizing Health Care Spending in the US

NPR’s Planet Money published two excellent graphs this week, comparing health care spending in the US now versus the 70s and 90s. For example, here’s what they reveal about hospital versus non-hospital spending:

In other words, hospitals have a shrinking proportion of the health care dollar, but not one that is shrinking very much. Despite so much reduction in length of stay, and so much pressure to control hospital costs, their contribution to health care spending hasn’t declined that much. (In fact, given the huge rise in health care spending since the 70s, it is clear that hospital costs are growing. Take that, DRGs!)

Then there is the question of who is paying for this. Turns out: out-of-pocket expenses have shrunk, proportionally, since the 70s:

How could this be? Especially with what I posted just the other day?

For starters, this graph does not include a person’s contribution to insurance costs as part of their out-of-pocket expenses. So if, say, a person buys a Medicare Supplemental insurance plan with their own money, that wouldn’t be called an out-of-pocket expense here. That would come under private insurance. Co-pays on Medicare, though, or on private insurance would count as an out-of-pocket expense. Kind of confusing.

And also keep in mind: these proportions are hiding the bigger story. Health care costs, even after accounting for inflation, have risen dramatically since the 70s. A third of a small pie is nothing compared to a quarter of a gargantuan one! (Click here to view comments)

One Price Does Not Fit All for Medical Fees