With its expansion of Medicaid eligibility, the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) was supposed to go a long way towards providing healthcare coverage to millions of uninsured Americans. That accomplishment was dealt a large blow by the Supreme Court, when it forbade the federal government from requiring states to expand Medicaid coverage. Nevertheless, many states plan to offer Medicaid to anyone with incomes at or below 138% of the Federal Poverty Limit (FPL). And more states might follow suit over time, under pressure from the healthcare industry, which likes its customers to be paying customers.

With its expansion of Medicaid eligibility, the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) was supposed to go a long way towards providing healthcare coverage to millions of uninsured Americans. That accomplishment was dealt a large blow by the Supreme Court, when it forbade the federal government from requiring states to expand Medicaid coverage. Nevertheless, many states plan to offer Medicaid to anyone with incomes at or below 138% of the Federal Poverty Limit (FPL). And more states might follow suit over time, under pressure from the healthcare industry, which likes its customers to be paying customers.

However, even if Medicaid coverage expands under Obamacare, a big potential problem remains—many physicians will be unwilling to care for Medicaid patients. But how many physicians and which ones?

A July study in Health Affairs estimated the percent of physicians from a wide range of specialties who were unwilling to take on new Medicaid patients in 2011 and 2012. What specialty would you guess was least likely to accept new Medicaid patients? …(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Health Insurance in Massachusetts: Paying More, Getting Less

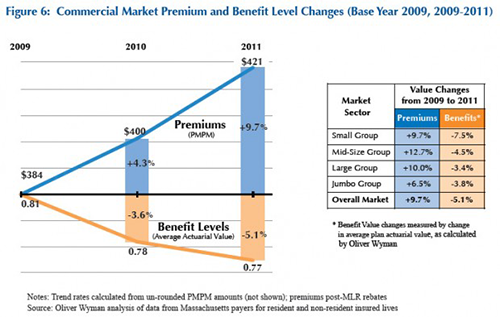

A new report out of Massachusetts concludes that people there are paying more for their health insurance, at the same time that the services covered by their insurance are declining. Here’s a picture from a Kaiser summary of the report:

The Kaiser story also points out that a big problem in Massachusetts is that people continue to receive care at the most expensive hospitals and clinics, rather than local centers that would be much more affordable. Remember: Massachusetts is several years ahead of the rest of the country, in adopting the kind of changes that are part of Obamacare. Keep your eyes on Massachusetts, as it struggles to control these costs. Because that may be where the rest of the country is headed soon.

(Click here to view comments)

Beware of Cancer Metastasizing to Your Wallet

Joanne Reed’s breast cancer was discovered at an early stage, early enough that her doctors would be able to remove the tumor with surgery (either a mastectomy or a lumpectomy) and then, with a touch of chemo, she would face a decent chance of living out her life without a recurrence.

Joanne Reed’s breast cancer was discovered at an early stage, early enough that her doctors would be able to remove the tumor with surgery (either a mastectomy or a lumpectomy) and then, with a touch of chemo, she would face a decent chance of living out her life without a recurrence.

But then Reed’s cancer metastasized to her wallet: “I was working full-time at the time [of my cancer diagnosis] and had pretty good insurance. But I still had co-pays…anyway, I kept getting bills.” And unfortunately, she kept getting bills at the same time as her income declined, because the treatments made it difficult for her to continue working: “So our income was cut in half. And with a husband who is disabled [with schizophrenia]…and I had also had some credit card debt from the past…”

Reed is one of several dozen women who participated in a Duke study (led by an oncologist, Yousuf Zafar) on which I have been collaborating. The study explores the financial burdens created by cancer diagnoses. Reed spoke anonymously to our research team (Reed is a pseudonym) and her story is as tragic as it is routine. Across our interviews, we discovered a wide range of medical and social circumstances impacting patients’ lives. Some people had early stage cancers, others had more advanced disease; some people had health insurance and others didn’t. But almost to a person, one fact was consistent across these patients—none of them expected that their cancer treatments would cause as much financial distress as they did.

Even people with decent health insurance may be one serious illness away from economic calamity…(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Procedures and Prices: Both Contribute to Health Care Spending Increases

For very good reason, there has been lots of attention on healthcare prices in the United States lately. We spend more on healthcare in this country than anywhere else in the world, and we also charge higher prices for the healthcare we offer. Physicians in the United States make much more than their counterparts elsewhere in the world. Pharmaceutical companies know that the US market is where they are going to make a good share of their profits, because they can’t charge the same high prices elsewhere that they do in the United States.

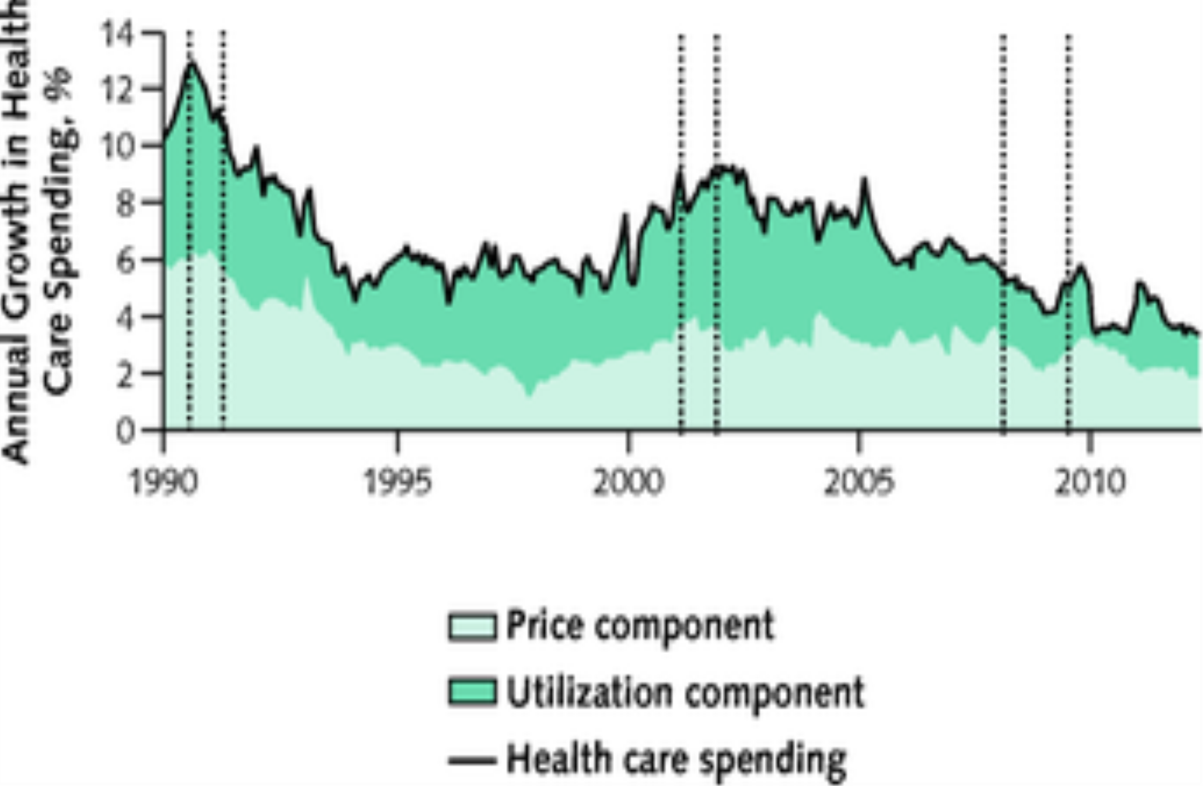

But keep in mind: we spend more on health care from year to year not just because of high prices, but also because we provide more healthcare services to more people. The relative contribution of prices and procedures is nicely summarized in this figure, reproduced from an article in the Annals of Internal Medicine:

If we want to get healthcare costs under control, we can’t focus on price alone.

(Click here to view comments)

The Pain of Anticipation

In a recent edition of the New Yorker, the magazine published a story by Dashiell Hammett and one of the paragraphs in that wonderful story nicely captures the way that waiting for something bad to happen can be worse than experiencing that bad thing. In the scene, a group of people stand on the sidewalk gazing up at the second-story window of a building that has caught fire. No firefighters arrived yet. They see a child’s face looking out the window, the child completely unaware that he is in a burning building, with smoke and flames soon to descend upon him. The onlookers are aghast at the sight of this poor innocent child about to be overtaken by the worst kind of misery:

In a recent edition of the New Yorker, the magazine published a story by Dashiell Hammett and one of the paragraphs in that wonderful story nicely captures the way that waiting for something bad to happen can be worse than experiencing that bad thing. In the scene, a group of people stand on the sidewalk gazing up at the second-story window of a building that has caught fire. No firefighters arrived yet. They see a child’s face looking out the window, the child completely unaware that he is in a burning building, with smoke and flames soon to descend upon him. The onlookers are aghast at the sight of this poor innocent child about to be overtaken by the worst kind of misery:

It was terrible, and it held him: a stupid flat face into which panic must come each instant – and did not. If the child had cried and beat the pane with its hands there would have been pain in looking at it, but not horror. A frightened child is a definite thing. The face at the window held its blankness over the men in the street like a poised club, racking them with the threat of a blow that did not fall.

As Tom Petty used to sing in that hit song: the waiting is the hardest part.

(Click here to view comments)

Should Patients Be Able to Receive "PFO Occluders" Outside of Research Trials?

Ten years ago, my tennis partner suffered a stroke. He was a sixty-year-old at the time, working to move up into the top ten players in his age group. In the country! You could not have found a healthier sixty-year-old. He played tennis three-plus hours a day, scampering across the court like a hyperactive adolescent. In other words, he was not the kind of cigarette smoking, hypertensive elderly man you would expect to experience a stroke from clogged and battered arteries.

Ten years ago, my tennis partner suffered a stroke. He was a sixty-year-old at the time, working to move up into the top ten players in his age group. In the country! You could not have found a healthier sixty-year-old. He played tennis three-plus hours a day, scampering across the court like a hyperactive adolescent. In other words, he was not the kind of cigarette smoking, hypertensive elderly man you would expect to experience a stroke from clogged and battered arteries.

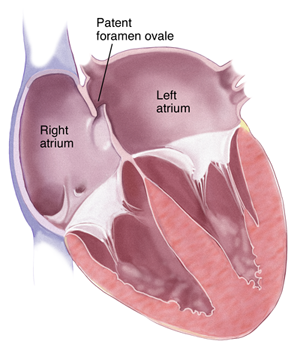

I wasn’t shocked to learn, then, that he had a PFO—a patent foramen ovale. The foramen ovale is a passageway connecting the right and left atrium in the heart, a crucial opening for all of us when we were fetuses because it allowed our bodies to shunt blood from the right and left side of the heart without having to pass through what, in those circumstances, were non-functional lungs. For most of us however, the first time we took a breath of air after being born, our foramen ovales began to close, the two sides of the wall separating the atria eventually fusing. But in the case of my tennis partner, that FO remained a PFO. He lived for sixty years unaware that there was a hole still open between the two sides of his heart. Eventually that PFO contributed to his stroke, providing an opening for a blood clot to sneak across to the left side of his heart where it then was pushed, with the contraction of his left ventricle, up towards his brain.

My tennis partner survived the stroke and was soon playing tennis again. Determined not to experience another stroke, he chose to have his doctors close his PFO.

But should he have made that choice? And should his insurance company have paid for the procedure? …(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Regulation of Nurse Practitioners

In a recent post, I pointed you towards a very nice article by Jason deBruyn about controversies over the role of nurse practitioners in providing primary care. A recent study in the journal Health Affairs showed that when states loosen up their regulations over what nurse practitioners can do, the percent of people receiving primary care from such practitioners grows.

It’s important to note that the percentages still remain quite low. I don’t think physicians should feel incredibly threatened by this. The primary care needs of our country are growing faster than physicians can meet them. We are all in this together.

It’s important to note that the percentages still remain quite low. I don’t think physicians should feel incredibly threatened by this. The primary care needs of our country are growing faster than physicians can meet them. We are all in this together.

(Click here to view comments)

More Information on the Cost of Post-Acute Care

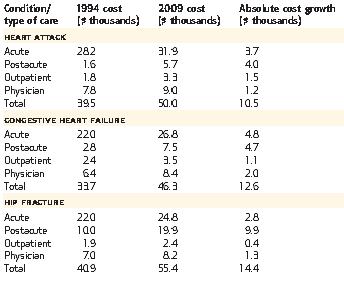

In a recent Forbes post, I wrote about geographical variation in healthcare expenses, and pointed out that a lot of this variation occurs after people leave hospitals. That’s when people end up in nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities and the like. Well it turns out, not only is there great variation in these expenses, but these are also places where healthcare costs have risen relatively quickly over the past 15 years. Consider these data from a recent study in Health Affairs:

The hip fracture data is especially notable. The cost of acute care – presumably of the surgery and postop recovery – has risen pretty slowly over this time period. But once you leave the hospital? Much more dramatic increase in expenses. I’m curious to hear people’s ideas on why expenses have grown so much more rapidly in the setting. Are insurance companies less able to negotiate the cost of post-acute care? Will bundled payments take care of this problem?

(Click here to view comments)

Should We Care About Hospital Prices?

I have been writing quite a bit about healthcare price transparency lately. And so have a lot of other people. Many of us have been pointing to insane variation in how much hospitals charge for their services. Walk across the street, and you might see the price of a routine healthcare service rise two or threefold.

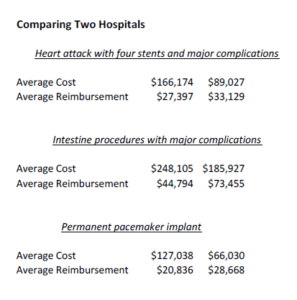

But of course what hospitals say they charge for services, and what theyreceive for those services, are usually very different things. And these data, posted a while ago on the Washington Post website, perfectly illustrate that issue:

What is going on here? …(Read more and view comments at Forbes)

Expanding the Role of Non-Physicians in Primary Care

I’m back to blogging again, and thought I’d return to a topic I have blogged about recently: expanding the role of non-physicians in primary care. A very talented journalist in North Carolina, Jason deBruyn, wrote a nice piece which I am indenting below, laying out some of the controversies.

Debate settles in on costs versus quality of care

Jason deBruyn

Staff Writer- Triangle Business Journal

Email | Twitter

RALEIGH – Health care economists largely agree that expanding the role of nurse practitioners in primary care would likely decrease overall health care costs.

But it could also reduce the level of care that patients receive because nurse practitioners do not go through the same lengthy schooling and residency training as do medical doctors.

As the nation continues to search for ways to reduce health care spending, considering the cost-benefit of costs vs. level of care becomes a factor in the equation.

Physicians argue that their time in medical school and residency better prepare them to catch a rare case if they notice something unusual about a patient. That might be true, but the overwhelming majority of primary care visits are for patients with diabetes, high blood pressure, or other relatively routine issues. For a vast majority of these cases, nurse practitioners are equipped and trained to provide the proper care.

Dr. Peter Ubel, a medical doctor, behavioral scientist and a professor of public policy at Duke University, says the same debate can be kicked up a food chain one level. Thyroid specialists, for example, would be better equipped than primary care physicians to catch a rare or specific thyroid illness, but for the majority of patients, primary care physicians can properly diagnose a patient and refer her or him to a specialist if needed – and do it at a lower cost.

By presenting to primary care physicians, instead of more expensive specialists, patients receive care that is good enough but at less cost. Nurse practitioners make that same argument one step down, saying they can provide care that is good enough and refer to doctors and specialists as needed.

“For many primary care visits, you don’t need four years of medical school and three years of residency,” Ubel says. “We could save a lot of money with very little medical harm.”

Many states have reduced regulations on nurse practitioners, allowing them to fill in primary care gaps. There is no published study that analyzes health outcomes in states with strict nurse regulations against states with looser nurse regulations, partly because eliminating all other variables is nearly impossible.

Looking purely at the economics, however, reveals probable savings. By using Texas as a model, Ray Perryman, nationally known economist and CEO of the Waco, Texas-based Perryman Group, estimates immediate savings of $16 billion in the health care market by greater use of nurse practitioners and other advanced practice nurses.

Elsewhere, a group led by Robin Newhouse, a registered nurse and chairwoman of the Organizational Systems and Adult Health at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, found consistent evidence that cost-related outcomes such as length of stay, emergency visits, and hospitalizations for nurse practitioner care are equivalent to those of physicians.

Cost-effectiveness starts with academic preparation. With less schooling and residency training, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing has long estimated that the preparation costs for nurse practitioners are between 20 percent and 25 percent that of physicians. In 2009, for example, the total tuition cost for nurse practitioner preparation was less than the cost of one-year tuition for medical preparation, according to the association.

Similarly, the association reports lower salaries for nurse practitioners. Using data from the American Medical Group Association, total compensation for primary care physicians ranged from $208,658 for a family physician to $219,500 for internal medicine. By contrast, the average full-time salary for nurse practitioners across all types of practice was $97,345, according to AANP.

Especially as more people begin buying health insurance next year under the Affordable Care Act, gaps in primary care could grow larger. Physician shortages, particularly in the field of primary care and in rural areas, have been widely predicted for two years now.

“The economic pressures are growing so much that we are at a stage that we are more willing to expand the role of nurse practitioners and advance practice nurses,” says Ubel. “(For primary care,) it’s better to see a nurse practitioner next week, than wait three or four weeks to see a primary care physician.”