Last summer, Facebook received terrible press for running experiments on its users, adjusting the proportion of happy and unhappy posts at the top of people’s news feeds to see how that effected their moods. Shortly after that controversy surfaced, OK-Cupid founder Christian Rudder proudly announced “we experiment on human beings.” He unabashedly admitted that he runs experiments without users’ consent, but pointed out that this is a practice common to the majority of internet companies. What headline will grab the most clicks on HuffPo? You can guess that this company has run scads of experiments to answer this question. But Rudder didn’t simply run harmless little trials on whether putting the word “bikini” in a headline leads more people to click on it. Instead, his company actively lied to its consumers.

Last summer, Facebook received terrible press for running experiments on its users, adjusting the proportion of happy and unhappy posts at the top of people’s news feeds to see how that effected their moods. Shortly after that controversy surfaced, OK-Cupid founder Christian Rudder proudly announced “we experiment on human beings.” He unabashedly admitted that he runs experiments without users’ consent, but pointed out that this is a practice common to the majority of internet companies. What headline will grab the most clicks on HuffPo? You can guess that this company has run scads of experiments to answer this question. But Rudder didn’t simply run harmless little trials on whether putting the word “bikini” in a headline leads more people to click on it. Instead, his company actively lied to its consumers.

OK-Cupid is a dating site, you see, which purportedly learns enough about people who use its services to match them up with compatible partners. “We took bad pairs of matches,” Rudder proudly announced, “and told them they were exceptionally good for each other.” They found almost no reduction in how likely such people were to pursue relationships with each other.

Putting aside the evidence Rudder collected of the uselessness of his company’s matching technology, his experimental method raises questions about whether it can ever be ethical to experiment on people without their consent.

Well, I, like Rudder, have conducted social experiments on unconsenting, unwitting people. But the experiments I run differ in very important ways from the unacceptable methods with which OK-Cupid ran its experiment. Given the potential for companies like Facebook and OK-Cupid to cause real harm with their research, we consumers should at a minimum demand that such companies get feedback from independent ethics boards.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Are Patients Harmed When Physicians Explain Things Too Simply?

A quick quiz before we start today’s lesson.

A quick quiz before we start today’s lesson.

What do we call a tree that grows from acorns?

What do we call a funny story?

What sound does a frog make?

What is another word for a cape?

What do we call the white part of an egg?

On that last question, were you tempted to answer “yolk?” If so, you are in good company, because most people give that answer even though the correct answer is “albumen.” People answer yolk – after oak, joke, croak, and cloak – because that’s the fast choice. Primed by rhymes, people provide the wrong answer.

Sometimes fast-thinking is not so good. Which raises an interesting question for physicians trying to help patients navigate important medical decisions Will they harm patients by explaining things so simply that patients make fast, erroneous choices? (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Healthcare.gov 3.0–Improving the Design of the Obamacare Exchanges

I joined two other, much smarter, colleagues in calling for the use of behavioral economics and decision psychology to improve the design of the websites people use to purchase health insurance in the U.S. That article came out today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here is a taste:

I joined two other, much smarter, colleagues in calling for the use of behavioral economics and decision psychology to improve the design of the websites people use to purchase health insurance in the U.S. That article came out today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here is a taste:

In October 2013, the Affordable Care Act introduced a new insurance market — state and federal exchanges where people can purchase health insurance for themselves or their families. Although the rollout of the exchanges was disastrous, around-the-clock efforts fixed many of the biggest technical problems, and nearly 7 million people purchased insurance in the new market. The second round of enrollment exposed some new problems with the exchange websites — for example, Colorado’s website had difficulty determining whether people were eligible for tax credits — but these problems paled in comparison with those encountered when the exchanges were first rolled out. In short, we have a largely glitch-free system of health insurance exchanges that present millions of people with a robust set of health insurance choices.

Which means that it will soon be time to tackle the much more challenging job of designing exchange websites in ways that maximize the chances that consumers will choose plans best suited to their needs and preferences. If the first round of open enrollment was primarily about avoiding catastrophe and the second round was about ironing out wrinkles in the underlying programming code, then version 3.0, in our view, should focus on redesigning the way exchanges present their insurance choices, to avoid features known to bias people’s decisions.

When It Comes to Cancer Screening, Are We All Nuts?

In a recent Health Affairs article, David Asch and I wrote about how hard it can be to stop screening aggressively for things like breast and prostate cancer even when the evidence suggests we are doing more harm than good. Well, journalist Steven Petrow has a nice piece in the Washington Post looking at the good old testicular exam. Lots of nice insights, so I thought I’d share it:

In a recent Health Affairs article, David Asch and I wrote about how hard it can be to stop screening aggressively for things like breast and prostate cancer even when the evidence suggests we are doing more harm than good. Well, journalist Steven Petrow has a nice piece in the Washington Post looking at the good old testicular exam. Lots of nice insights, so I thought I’d share it:

Late last year, “Today” show anchors Willie Geist and Carson Daly took one for the men’s team when they underwent testicular cancer exams on live TV. Lots of predictable joking ensued, especially from co-anchor Savannah Guthrie, who ad-libbed: “When I heard what you guys were doing, I thought it was nuts!” The “attending” urologist, David Samadi of Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, also took to wordplay, asking: “Who’s going to play ball first?” Geist stepped up.

Within minutes both anchors received clean bills of health along with Samadi’s congratulations for getting the exams. Samadi also encouraged the rest of maledom to perform testicular self-exams monthly in the interest of early detection, which he said can save lives — but do they?

Nearly 9,000 cases of testicular cancer in the United States are diagnosed every year — especially among men ages 15 to 34, where it’s the most common cancer — so the “Today” segment seemed like a useful public service announcement.But unfortunately there’s no evidence that self-exams detect testicular cancer at an earlier stage, according to Durado Brooks, director of colon and prostate cancer prevention programs for the American Cancer Society. Even if these exams did, says Kenny Lin, an assistant professor of family medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, early detection has little, if any, bearing on outcomes for those who are diagnosed. Lin calls the “Today” segment “a stunt cloaked as a health message,” and he points out that even the august U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends against testicular cancer screening — a change from the past.

Other routine screening tests have also earned a thumbs down from the medical establishment in recent years, as more clinical evidence has been gathered showing them to be less beneficial than once thought. Among the tests no longer universally recommended: PSA screening for prostate cancer, breast cancer self-exams for women and mammograms for women younger than 50, and Pap smears for cervical cancer for women younger than 21. Not only do these exams have nearly no effect on outcomes, the task force said, they can sometimes do more harm than good.

Regarding testicular screening in particular, it “is unlikely to offer meaningful health benefits, given the very low incidence and high cure rate of even advanced testicular cancer” while “potential harms include false-positive results, anxiety and harms from diagnostic tests or procedures,” according to the task force.

So why do some doctors continue to recommend these screenings — and why do some patients still want them? (To read the rest of this article, please visit The Washington Post.)

The Power of Free

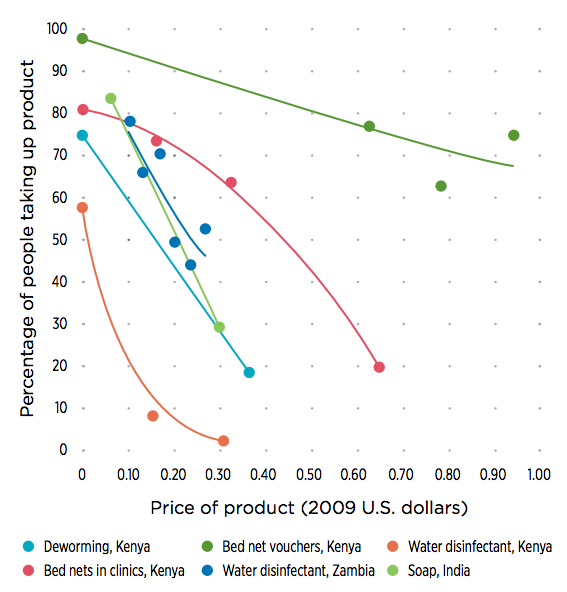

The Atlantic recently reproduced a figure showing just how much people like things when they are free. Specifically, they looked at health interventions and show that people are more likely to take up these interventions, or products, when they don’t cost anything.

And certainly, free is better than expensive, but free is also a whole lot better than cheap. There is something special about going from any price to no price:

What Causes Couch Potatoes To Eat So Many Potato Chips?

Do you eat when you’re bored? So do I. Then again, I eat when I’m not bored, too. So the real question is: do we all eat more when we’re bored than, say, when we’re highly entertained?

The answer, according to a clever study by Aner Tal and colleagues, is no. In fact, sometimes being energized by your environment may be the worst thing for your waistline.

In the study, Tal sat college students down in front of the TV with an array of tasty treats at their disposal – M&M’s, cookies, carrots and grapes. Tal then measured how many calories students consumed on average during 20 minutes of TV viewing where the students had no idea that their food consumption was being monitored.

When watching 20 minutes of the Charlie Rose Show, a PBS talk show (yawn!), students consumed a bit more than 100 calories of snacks, on average. But other students, picked at random to watch an excerpt from an action movie, The Island, ate twice that amount in the same period of time.

Double your fun and double your calories? (To read the rest of this post and leave comments, please visit Forbes.)

Has The "Nudge" Meme Gotten Out of Control?

A tweet recently came across my feed that captures a problem with the popularity of the nudge meme. The meme took off with the justifiable popularity of Thaler and Sunstein’s eponymous book, in which they promote the idea of influencing people to behave in their own best interests in situations where unconscious and even irrational forces might lead them astray. Thaler and Sunstein specifically promote behavioral interventions that do not restrict people’s freedom. They illustrate that concept with the idea of a cafeteria owner who intentionally places unhealthy foods at the end of the line, knowing that the cafeteria design will lower the amount of dessert people eat while still allowing diners to eat as much fruit and pie as they want.

In the tweet, a man who describes himself as being interested in behavioral economics reproduces a picture of a stop light in Italy on which the red light is significantly larger than either the yellow or green lights. “Simple #nudge,” the tweeter points out, “to raise prominence of key information – enlarged red/stop light.”

I understand that the concept of nudging is fluid. Like most ideas, it can’t be controlled even by its originators. The meaning of words is a social enterprise. But as part of that enterprise, I feel compelled to push back, to constrain the idea of nudges to more reasonable boundaries.

Let’s start by recognizing that a stop light is a weird context to talk about a nudge. (To read the rest of this article, and leave comments, please visit Forbes.)

Brilliant Nudge to Promote Physical Activity

The stairs to the left of the escalator don’t just look like a piano keyboard, but make musical sounds as people walk on each step.

Not convinced this will work? Check out this video, which shows people heading towards the escalator, and then changing direction when they realize how fun it will be to climb the stairs.

Not convinced this will work? Check out this video, which shows people heading towards the escalator, and then changing direction when they realize how fun it will be to climb the stairs.

A Picture Putting Risks into Perspective

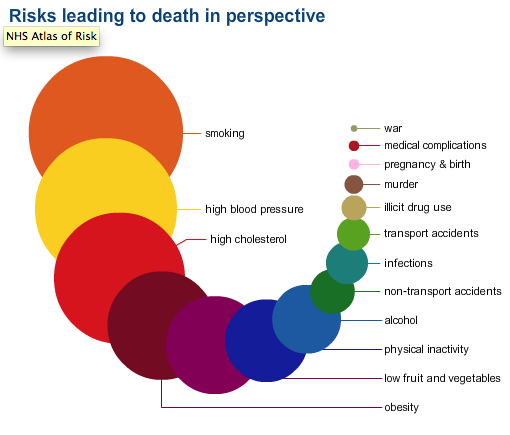

The National Health Service in the United Kingdom has recently disseminated a wonderful graphic, helping people understand how likely they are to die from scary things, like war and airplane accidents, versus less terrifying but deadlier hazards, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol:

In behavioral economics, we talk about something called the “availability heuristic,” a fancy term meaning – when we try to guess how likely things are to happen, we use as a simple rule of thumb how easily instances of those occurrences come to mind. Things that come easily to mind, we assume, are more common. It’s easy to think of airplane accidents, because they’re covered in the news. Nothing newsworthy about a 90-year-old man dying from smoking related illness. This graphic is powerful, because it acts as a visual reminder of what we really ought to be scared about.

In behavioral economics, we talk about something called the “availability heuristic,” a fancy term meaning – when we try to guess how likely things are to happen, we use as a simple rule of thumb how easily instances of those occurrences come to mind. Things that come easily to mind, we assume, are more common. It’s easy to think of airplane accidents, because they’re covered in the news. Nothing newsworthy about a 90-year-old man dying from smoking related illness. This graphic is powerful, because it acts as a visual reminder of what we really ought to be scared about.

How Healthy Food Could Make You Fat

Have you ever eaten a healthy meal, maybe some brown rice and stir-fried veggies, and found yourself ready for another meal just a short while later? Or, more often couldn’t overcome a hankering for a satisfying dessert to top off (and undermine the healthiness of) that meal?

Have you ever eaten a healthy meal, maybe some brown rice and stir-fried veggies, and found yourself ready for another meal just a short while later? Or, more often couldn’t overcome a hankering for a satisfying dessert to top off (and undermine the healthiness of) that meal?

As it turns out, this lack of satiety is not merely a function of the lack of calories in your entrée, but also reflects an unconscious connection between your perceptions of how healthy the meal is, and your hormonal response to said meal. That’s the bottom line of research conducted by Alia Crum, a researcher at Stanford University.

Crum presented people with vanilla milkshakes and convinced some people the shake was a no-fat, low-sugar health drink and others that it had enough sugar and fat to feed a large family. (Okay; slightly exaggerating.) She discovered that people eating the “healthy” milkshake (which, of course, was identical to the unhealthy one) experienced an elevation of a hormone called ghrelin, which slows metabolism and stimulates appetite. Those believing that the shake was unhealthy, on the other hand, experienced a drop in ghrelin, and thus were more satisfied.

Think about what this means for dieters. They eat healthy meals in hopes of losing weight and their damn bodies fight back, hoarding on to the calories they’ve consumed while, simultaneously, telling them they need to consume even more calories. (To read the rest of this article and leave comments, please visit Forbes.)