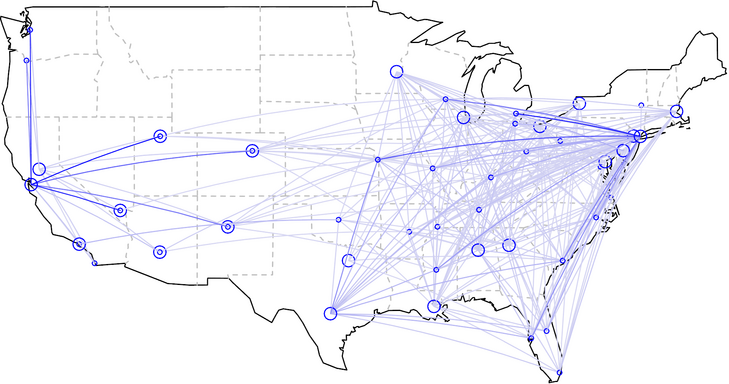

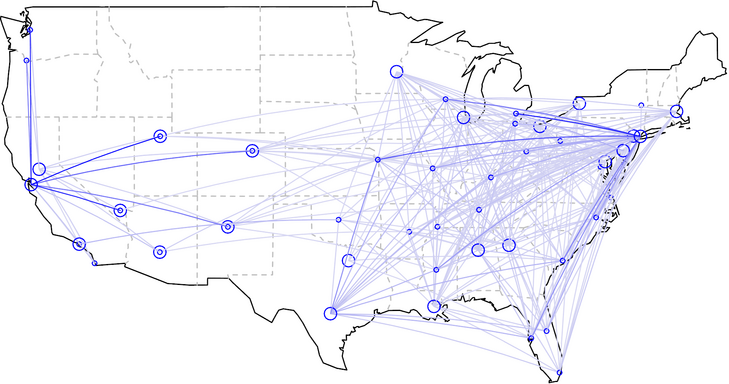

As I have described in two earlier posts, here and here, the transplant system in the US suffers from terrible geographic disparities. People needing liver transplants in Northern California wait more than six years on average for an organ to become available, versus only three months in places like Memphis Tennessee. The solution to the geographic problem seems straightforward: stop giving priority to local transplant candidates over needier candidates in other locations. And the only barrier to fixing the problem appears to be the recalcitrance of transplant centers who are benefiting from the current system. Indeed, in 1999, the Institute of Medicine called upon the transplant community to reduce geographic disparities in transplant access by sharing organs more widely. By that time, the science of organ preservation had already advanced to the point where organs like livers and kidneys could be transported successfully from New York to Tennessee and still be healthy enough to thrive after transplantation. Yet a decade and a half later, the system remains unchanged. Bruce Vladek, former director of Medicare and Medicaid, laments that “the transplant community has largely ignored the [IOM’s] recommendation.” Sharing transplantable organs would give patients a more equal chance of receiving transplants, regardless of where they live, and would also eliminate the unfair advantage patients receive when they list themselves at multiple transplant centers.

But this solution is not as straightforward as it seems. If the transplant system begins flying organs across transplant regions, those centers with the longest waiting lists, typically filled with the sickest patients, would become net importers of transportable organs. Huge programs like the University of Pennsylvania would become even bigger. And some, perhaps most, small transplant programs would go out of business, unable to compete for scarce organs when they become available. With much shorter waiting lists, the chances that one of their patients would be the top candidate for an available organ would be relatively slim, like competing in a lottery where everyone else has five times as many tickets as you do. Moreover, if small transplant programs collapse, that could doom the hospitals and medical centers housing those programs. The money the centers lose on, for instance, treating Medicaid patients with pneumonia would no longer be balanced by the money they make transplanting people with liver disease. Finally, the loss of the smaller programs could make it harder for patients in rural communities to undergo transplantation evaluations.

In trying to make our transplant system fairer, we are forced to decide whether we are willing to drive small transplant programs out of business. Indeed, questions about whether to protect small medical centers from the business of medical practice are becoming increasingly relevant across American healthcare, even beyond the boundaries of transplantation medicine. Small medical centers are under intense pressure to compete for patients, in part because they have a difficult time matching the price of high-volume centers. Consider a medical center like the Mayo Clinic. Because of its size and experience, the Clinic has become more efficient than many smaller medical centers, the result being a growth in market share, as patients fly across the country to Rochester Minnesota for their artificial hips and their pacemaker implants, their healthcare savings more than making up for the cost of the trip. Such market-share dominance is already becoming an issue in organ transplantation. Wal-Mart has contracted with the Mayo Clinic to perform transplants on any of its employees who develop organ failure. Wal-Mart even pays to house these employees near one of Mayo’s hospitals, so they can wait for organs to become available and recover from their subsequent transplant.

Contracting with the Mayo Clinic makes sense for Wal-Mart, because the company can obtain relatively low price transplants for its employees. Mayo’s size offers it efficiencies of scale not available to smaller transplant programs, and Wal-Mart’s size no doubt enabled it to negotiate discounted rates for the care its employees receive.

Large medical centers not only have efficiencies of scale, that allow them to charge lower prices, but often provide higher quality of care for complex conditions, because they gain more experience treating such conditions. Research has shown that, all else equal, experienced healthcare providers often provide better care than less experienced ones. For instance, among patients with pancreas tumors, 14% die shortly after surgical removal of the tumor at hospitals where such procedures occur one or two times per year. In hospitals where such procedures are more common, postoperative mortality is less than 4%.

Debates about organ allocation must consider this relationship between the volume and quality of healthcare. David Axelrod, a Dartmouth transplant surgeon, conducted a study of liver transplant outcomes at small and large transplant programs, comparing the smallest third of programs (which transplanted a median of 21 patients per year) to the largest third of programs (which transplanted more than 90). He found, all else equal, that patients transplanted at the smaller programs were 30% more likely to die in the first year after their transplant. “The differences were striking,” notes Axelrod, “but that does not mean all patients should head to large transplant centers, not with the way our current system is set up. After all, some of those large programs, like ones in San Francisco where Steve Jobs lived, also have long waiting times. If you have a large center with great post-transplant outcomes, but most patients die before they ever get transplanted,” he asked me, “is that the best option for the patients?”

I interpreted that as a rhetorical question. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Your New Liver Is Only a Learjet Away: Part 1 of 3

The forty million dollar Gulfstream jet landed at Memphis International airport in the early morning hours, its schedule hastily arranged earlier that day from Northern California, where the flight originated. Waiting on the tarmac was Dr. James Eason, head of transplant surgery at Methodist University Hospital, who planned on whisking the passenger to the operating room for a liver transplant. The passenger rushed to Memphis not because he lived in Memphis and happened to be out of town when an organ became available, but rather because he knew that flying from his home in Northern California to Tennessee would give him his best chance of receiving a life-saving organ.

You see, the demand for transplantable livers in Northern California far outstrips the supply, meaning there is a decent chance a patient with end-stage liver disease will die before a replacement organ becomes available. But in Tennessee, the number of people waiting for a liver transplants is significantly smaller, per capita, than California, and as a result the supply of transplanted livers is much better matched to the demand for such organs. As a result of these geographic variations in supply and demand, patients in Northern California wait more than six years, on average, for a liver transplant, whereas the majority of patients in Tennessee receive new livers in less than three months.

That’s right: six years versus three months!

The passenger on the Gulfstream that morning was Apple co-founder and CEO, Steve Jobs. After being told he needed a liver transplant, Jobs had learned about the huge disparity in waiting time between California and Tennessee, and arranged to get placed on the transplant waiting list in both locales, knowing he could fly to whichever location came up with the first available organ. So when he got a call from Memphis explaining that a 20 year old man with a compatible blood type had died in a car crash earlier that day, he summoned his flight crew and made his way to Tennessee.

Steve Jobs walked out of the plane that morning a frail shadow of his former self. Pancreatic cancer had spread to his liver and, without a transplant, he had only weeks or months to live. Thanks to that early morning flight and the talents of his surgeon, Jobs received a transplant later that day and would survive two and a half more years, a time in which he introduced the world to the iPad and to a talking phone assistant named Siri.

It was wonderful for Jobs and his loved ones that he was able to receive a transplant that day. But was it fair that Jobs could afford to charter a jet from California to Tennessee to undergo a transplant, while thousands of equally sick Californians waited at home for livers that didn’t always come in time?

Currently, less than 6% of transplant candidates are listed at multiple transplant centers. And less than 2% get listed at transplant centers a long-distance from where they live, like Jobs did. After all, there’s not much reason for Northern Californians to get waitlisted in Tennessee if they cannot afford to rent a Gulfstream on short notice to get them to the transplant center on time. This Gulfstream deficiency may end soon, however, if a start-up company called OrganJet succeeds in its goal of “democratizing Steve Jobs’ transplant experience.” According to the vision of its founder, Sridhar Tayur, OrganJet will make sure that distant transplants are no longer available to only the wealthiest of patients. In fact, if insurance companies agree to pay for OrganJet’s services, as Tayur hopes, virtually everyone with healthcare coverage (be it Medicare or BlueCross/BlueShield) will be able to afford to fly to whatever location gives them the best chance of a life-saving transplant.

Would such democratization be a good idea? The answer to that question is more complicated than it appears at first glance, and raises questions about healthcare equity and regional variation in healthcare quality that are relevant well beyond the world of solid organ transplantation. The OrganJets of the world may finally force us, as a society, to talk more explicitly about just how fair we want our healthcare system to be.

In the US, hearts, kidneys and livers are distributed in a manner that strives to give every patient fair access to these life-saving organs. When a deceased donor’s liver becomes available, the local organ procurement organization (or OPO) offers the liver to the sickest transplant candidate, as long as that person’s blood type is compatible with the donor. Sickest-first is the rule. A rich investment banker with moderate liver disease won’t jump ahead of a bricklayer with severe disease. A white person won’t get priority over an African American, nor a man over a woman, nor a Christian over a Muslim, nor even a Protestant over (God forbid?) an atheist. In short, the liver transplant allocation system in the US is an astonishingly explicit and fair way to dole out life-saving resources.

For all its ethical wonders, however, the liver transplant system is far from perfect. For starters, people without health insurance often have a difficult time accessing the transplant waiting list. Critics quip that the first test physicians order when evaluating patients for transplant is a “wallet biopsy.”

There is another major problem, as Steve Jobs’ experience made so apparent. Barring the kind of wealth that enables people to rent out private jets, a person’s chance of receiving a life-saving transplant depends very much on where that person lives.

Sridhar Tayur first learned about geographic inequities in organ transplantation when he was an invited speaker at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management in October 2010. Out for dinner that night with colleagues, Tayur asked one of the Northwestern faculty members what research he did for a living. The professor, Baris Ata, said he was studying fairness in kidney transplant allocation, trying to determine, for example, whether patients who have been waiting longest for their kidney should receive priority over those more likely to benefit from available organs. Such a research topic is not out of the norm for a business school professor to study. Business schools are loaded with faculty who use advanced mathematical models to solve challenging real world problems. Just a few years ago, in fact, Alvin Roth won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for developing methods that have helped create kidney exchange programs that match chains of living donors to needy patients.

Tayur realized he had the perfect skill set to solve the problem of geographic inequity in organ transplant allocation, and that his solution would not require any policy changes. He had made an academic reputation for himself figuring out the mathematics of “inventory and supply chain optimization,”—in other words, for helping companies figure out how to allocate scarce resources to maintain the right amount of product on store shelves vs. warehouses. Tayur had even founded and run a software company, SmartOps Corporation, that helped companies make these decisions.

That company had left him, if not Steve-Jobs-wealthy, then at least financially secure: “When you do well in software,” he told me, “you do very well.”

Tayur realized he had an opportunity to give something back to society, as a social entrepreneur: “When I was running my software company,” he told me, “I started using private jets, because I wanted more time with my family while flying out to meet customers at difficult to reach locations. I noticed that there were lots of underutilized private jets lying around the country. I recognized this as a classic optimization problem.” Earlier in his academic career, serendipitously, he had written an academic paper on how to optimize the use of fractional jets, akin to the model used by Share-cars. “I understood private jets, and I understood optimization algorithms, so I knew I could figure out how to get people access to organ transplants, by finding them affordable flights to transplant centers that have shorter waitlists.”

OrganJet was born. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

An Eye for an Eye, a Cataract for…$4000?!

California is in the middle of an historic drought, with the government setting limits on how long people can sing in the shower. Farmers in the state may soon need to cut back on planting or production, as ground water dries up. But California is still fruitful ground for testing promising ways to improve how healthcare consumers, otherwise known as patients, shop for healthcare services. Specifically, California has shown that healthcare markets can be whipped into shape through the power of reference pricing.

In reference pricing, patients are given a maximum number of dollars from insurance to cover a given healthcare procedure with the understanding that if they choose to receive care from a more expensive provider, they will be responsible for any charges exceeding that limit. As I wrote in a previous post, California already used reference pricing to address high costs for knee and hip replacement. While many healthcare providers were charging $25,000 or $30,000 for the procedure, some were charging $60,000, $70,000, even $100,000.

The state of California realized it couldn’t continue to pay these exorbitant prices. It could have decided to force people to receive care from affordable providers. It could have regulated the price of these procedures. But instead the state took a different approach. It set a $30,000 limit on what it would reimburse patients. Overnight, state employees became discerning shoppers, avoiding high cost providers. Almost as quickly, providers began lowering their prices.

The wonders of efficient marketplaces. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

The Question Isn't Whether We Are Overdiagnosing Cancer, But How Much

Medical experts now agree that as a result of aggressive screening programs, we have an epidemic of cancer overdiagnosis in the United States. With mammograms finding tiny cancers and PSA tests discovering unpalpable prostate cancers, we are now unearthing some cancers too early for our own good.

Medical experts now agree that as a result of aggressive screening programs, we have an epidemic of cancer overdiagnosis in the United States. With mammograms finding tiny cancers and PSA tests discovering unpalpable prostate cancers, we are now unearthing some cancers too early for our own good.

What do experts mean by “overdiagnosis,” you ask? First, overdiagnosis is not the same as a misdiagnosis. If a pathologist looks under a microscope and classifies a group of benign cells as being cancerous, that is a misdiagnosis. Such misdiagnoses are an important consequence of cancer screening, causing patients to experience unnecessary anxiety and to undergo unnecessary treatments. Because no pathologist is perfect, aggressive screening programs will, by definition, lead to increases in such misdiagnoses. But these misdiagnoses do not qualify as overdiagnoses, the way experts use the term.

Second, overdiagnosis is not the same as a false positive test result. When a mammogram reveals a suspicious shadow, or when a PSA test is elevated, physicians usually follow up with additional tests, often culminating in a biopsy of the suspected lesion. When that testing reveals that no cancer is present, the screening test (the mammogram or the PSA test) is said to have created a “false positive,” result. It sent out a false alarm. Once again, false alarms are an important side effect of cancer screening. And more aggressive screening programs (yearly mammograms rather than every other year, for example) will necessarily lead to an increase in false positive test results. By some estimates, women beginning annual mammograms at age 40 will face a 50% lifetime risk of a false positive test. In other words, this is a burden of screening that we need to keep in mind when deciding how aggressively to look for a cancer. But false positives are not the same thing as overdiagnoses.

So what does it mean to overdiagnose cancer?

According to cancer epidemiologist Ruth Etzioni: “Overdiagnosis occurs when screening detects a tumor that would not have presented clinically in the absence of screening.” For example, if a mammogram reveals a tiny breast cancer in a 103-year-old woman, a cancer that if left alone would not grow large enough to cause symptoms (much less death) for another decade, that mammogram would probably have overdiagnosed her cancer—if she had never had that mammogram, she would have lived the rest of her life (maybe to 104 or 107-years-old) blissfully unaware that a small breast cancer was growing inside her body.

The example of this hypothetical 103-year-old woman is obviously an extreme one, meant to illustrate what experts mean by overdiagnosis. But it makes one thing clear. Cancer overdiagnoses are cases of real and true cancer. In this hypothetical case, for example, the tumor in this woman’s breast really was malignant. The mammogram did not lead to a misdiagnosis or to a false alarm. Instead, the mammogram discovered a cancer that, while real, would not have ever influenced this woman’s life. In her case, in fact, the diagnosis of this cancer would only act to harm this woman, by causing anxiety and potentially by leading to harmful treatments. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

If You Look for Cancer, You'll Find It

What would you like first: the good news or the bad news? Let me start with the bad. Life expectancy among patients in the U.S. with thyroid cancer lags behind that in Korea. In fact, the vast majority of patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer in Korea are cured of that illness, a statement I can’t as easily make about the U.S.

What would you like first: the good news or the bad news? Let me start with the bad. Life expectancy among patients in the U.S. with thyroid cancer lags behind that in Korea. In fact, the vast majority of patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer in Korea are cured of that illness, a statement I can’t as easily make about the U.S.

The good news? Life expectancy among patients in the U.S. with thyroid cancer lags behind that in Korea.

Okay, I kind of pulled a fast one on you. I tried to mislead you into thinking it is bad when cancer patients in another country out-live cancer patients in the U.S. On the surface, living longer after experiencing a cancer diagnosis seems to be a good thing. All else equal, it is better to survive cancer than to die from it.

But all else is far from equal when it comes to thyroid cancer in the U.S. versus Korea. (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Millions To Be Made On…Generic Drugs?

It is well accepted among health economics wonks that the lion’s share of pharmaceutical company profits come when these companies hold exclusive rights to their products. Once their blockbuster pills go “generic,” competitors enter the marketplace and profits plummet. Consider captopril, a groundbreaking heart failure medication introduced in the early 80s by Bristol-Myers Squibb under the trade name Capoten. After making a fortune for the company, captopril went generic in 1996. By 2013, you could purchase a captopril pill for the lofty price of…hold your breath…1.4 cents.

Not many fortunes to be made at that price.

Of late however, the well-accepted cheapness of generic drugs has come under question, in the face of surprising price hikes for long time medications. As reported in the New England Journal of Medicine by Jonathan Alpern and colleagues, captopril has experienced a 2800% price hike. Okay that still leaves the pill pretty affordable, at 40 cents a pop, but that’s still a pretty hefty price hike for a generic pill that competes against other generic medications.

The Hidden Psychology of Antibiotic Prescribing

Experts in decision psychology and behavioral economics have conclusively shown that humans, those silly creatures, are not always rational decision makers. They let unconscious forces influence their thinking, and not always for the better.

But of course, doctors aren’t human. Right?

Well, here is some evidence of just how human we doctors are. The odds of us prescribing antibiotics to our patients varies by the time of day, as we become more or less fatigued:

The High Price of Affordable Medicine

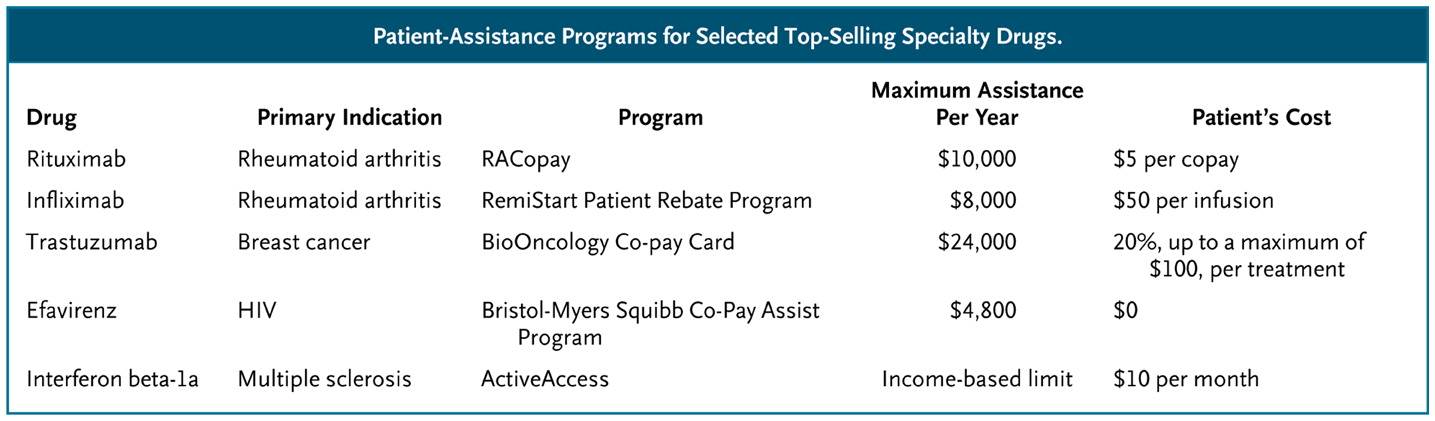

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

In the old days, blockbuster drugs were moderately expensive pills taken by hundreds of thousands of patients. Think blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes pills. But today, many blockbusters are designed to target much less common diseases, illnesses like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis or even specific subcategories of cancer. These medications have become blockbusters not through the sheer volume of their sales, but as a result of their staggeringly high prices. Tens of thousands of dollars per patient, per year.

The high cost of such blockbuster specialty drugs creates significant financial burden for many patients. When a drug costs $90,000 per year, and a patient pays 10% of that cost, we are talking about a serious chunk of change. Not surprisingly, as these out-of-pocket costs rise, so too do the rates of “non-adherence,” medical lingo for “the patients didn’t take the medicines that I, their doctor, thought they should take.” Non-adherence used to be called noncompliance, which sounded too paternalistic. Now some experts are shifting to an even less judgmental language of “medication abandonment.” Indeed, here is a picture of the likelihood that patients will stop taking specialty drugs as a function of their out-of-pocket costs:

What can we do to help patients afford these medications?

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

Are Patients Harmed When Physicians Explain Things Too Simply?

A quick quiz before we start today’s lesson.

A quick quiz before we start today’s lesson.

What do we call a tree that grows from acorns?

What do we call a funny story?

What sound does a frog make?

What is another word for a cape?

What do we call the white part of an egg?

On that last question, were you tempted to answer “yolk?” If so, you are in good company, because most people give that answer even though the correct answer is “albumen.” People answer yolk – after oak, joke, croak, and cloak – because that’s the fast choice. Primed by rhymes, people provide the wrong answer.

Sometimes fast-thinking is not so good. Which raises an interesting question for physicians trying to help patients navigate important medical decisions Will they harm patients by explaining things so simply that patients make fast, erroneous choices? (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)

The Lost Art Of Not Ordering A CAT Scan

She didn’t talk like a stroke victim. “I…I…I…k…kkk…can…can…can’t…t…t…t…talk.” She struggled with her words, struggling on early syllables, only to then spurt out full and correct words. “N…N…N…No.” Recognizing this unusual speech pattern, the neurologist Allan Ropper, author of Reaching Down the Rabbit Hole, expertly queried the patient and her loved ones, and determined she had just experienced a stressful break up with her boyfriend. “From the very first sounds out of her mouth,” Ropper writes, “I concluded that it is very unlikely that we are dealing with damage to her brain from a stroke, seizure, or any other acute problem.”

She didn’t talk like a stroke victim. “I…I…I…k…kkk…can…can…can’t…t…t…t…talk.” She struggled with her words, struggling on early syllables, only to then spurt out full and correct words. “N…N…N…No.” Recognizing this unusual speech pattern, the neurologist Allan Ropper, author of Reaching Down the Rabbit Hole, expertly queried the patient and her loved ones, and determined she had just experienced a stressful break up with her boyfriend. “From the very first sounds out of her mouth,” Ropper writes, “I concluded that it is very unlikely that we are dealing with damage to her brain from a stroke, seizure, or any other acute problem.”

The residents [physicians-in-training] pushed for an emergency CT, also known as a CAT Scan. Ropper knew better and explained why they should slow down and rely on their clinical examination findings “but they feel the stroke issue has got time value,” Ropper writes. “They prevail, and she heads off to the floor to get a big dose of radiation.”

What?!?!?! (To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)