How to Figure Out the Cost of Your Medical Care

Here is a link to an article from CBS News with some very practical advice on this thorny topic. I’m excited to say that some of our research on physician/patient communication was mentioned in the article. Enjoy it!

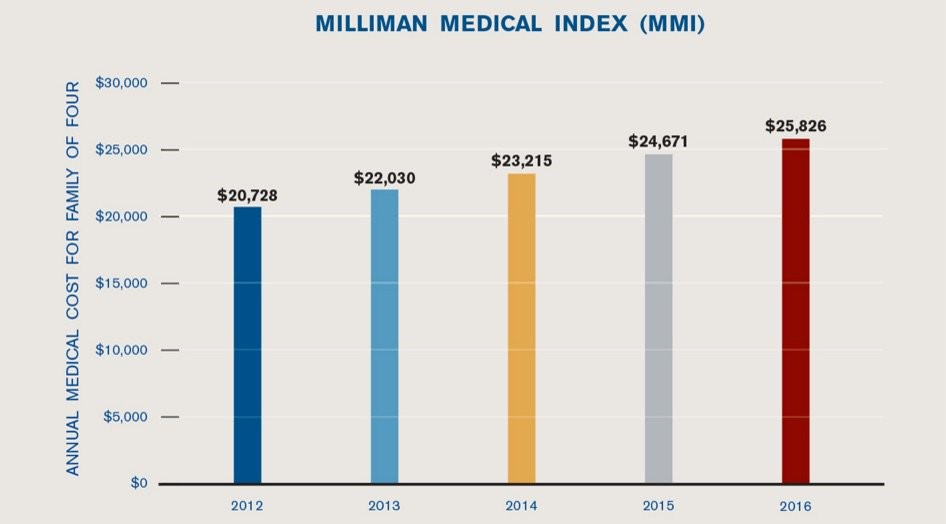

If you’re like most people, you’re paying more for your health care — and stressing about it, too. Average annual out-of-pocket costs for people in the workforce have increased almost 230 percent in the past decade, reports Kaiser Family Foundation.

Out-of-pocket costs are the main reason for the increase in underinsured Americans — people with medical bills that are more than they can afford. More than 30 million people are in that category, according to the Commonwealth Fund 2014 Biennial Health Insurance survey. Half of them reported problems with medical bills or debt, and 44 percent reported not getting the care they needed because of the expense.

No wonder 66 percent of consumers rank planning for out-of-pocket health care costs as the most challenging and stressful aspect of managing their health care, benefits firm Alegeus reported in a survey it released Wednesday.

Not only do consumers find paying for health care stressful, they also find it confusing. Nearly 60 percent of those surveyed said they found it difficult to understand the difference between benefit options, while 45 percent said the same about calculating what each option would cost, according to the report. “As we see a continued increase in premiums and deductibles, more of the health care cost burden is on consumers,” said Steve Auerbach, chief executive officer of Alegeus. “But they’re not prepared.”

What out-of-pocket health care costs are you likely to face? Here’s a brief rundown.

To read the rest of this article, please visit CBS News.

Out of Control Physicians: Too Many Doctors Doing Too Many Things to Too Many Patients

My father is 92 years old, and I am beginning to wonder whether the best thing for his health would be to stay away from doctors. That’s because well intentioned physicians often expose their elderly patients to harmful and unnecessary services out of habit. That’s certainly the message I absorbed after reading a recent issue of JAMA Internal Medicine that published three studies documenting the worrisome frequency with which internists like me over-test and over-treat our patients. I am going to briefly describe these three studies before laying out some ideas about what’s going on here.

One study explored the use of PSA screening among men with limited life expectancy. The PSA blood test is used to screen men for prostate cancer. The test is controversial, with some groups saying there is no evidence it benefits anyone and others saying it is a crucial way to reduce prostate cancer deaths. Despite this controversy, almost everyone agrees that when people have limited life expectancy–when, because of age and other illnesses, they probably have fewer than five years to live–the PSA test does more harm than good. But some physicians nevertheless continue to order PSA tests, even in men close to the end of their lives.

The study, which analyzed data from Veteran’s Affairs medical centers, found out that patients receiving care from “attending physicians”–more senior physicians–were more likely to receive harmful PSA tests than patients receiving care from physicians still in training. Indeed, 40% of patients expected to live five or fewer years received PSA tests from experienced physicians, versus only 25% receiving care from trainees :

The second study looked at carotid artery imaging in people 65 years or older. The carotid arteries are the large vessels on either side of your neck, the ones you can feel your pulse on. They are the main supply of blood to the brain. People who get blockages in their carotid arteries are at risk for strokes.

Carotid imaging with tests like ultrasound can identify narrowing of these important arteries, potentially revealing partial blockages in time to fix them before they fully occlude. In the old days, I’d place my stethoscope on a patient’s neck to listen to the harsh sound of blood squeezing its way through these blockages. Upon hearing a worrisome whoosh, I’d send my patient for imaging and then, if my suspicions were warranted, would refer the patient to a neurovascular surgeon, who would decide whether to perform a procedure to open up the artery.

But now, we physicians are being told to be more cautious. The benefits of all these tests and treatments aren’t so clear in many patients. The risks of the surgery can outweigh the benefits in people with no history of stroke or stroke-like symptoms. Nevertheless, many physicians continue to test and treat aggressively.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Three Things to Know about Future Healthcare Spending

For my entire life, a half century and counting, healthcare spending in the U.S. has almost always risen faster than inflation. Sometimes it’s relatively slow, sometimes it’s relatively fast, but no matter the time, healthcare spending is climbing. Getting healthcare spending under control is really important for us to do if we hope to have any money left in this country to spend on other important things. You know–like food, shelter, education. That kind of stuff.

So are we in the process of getting healthcare spending under control? A couple recent studies shed light on this question.

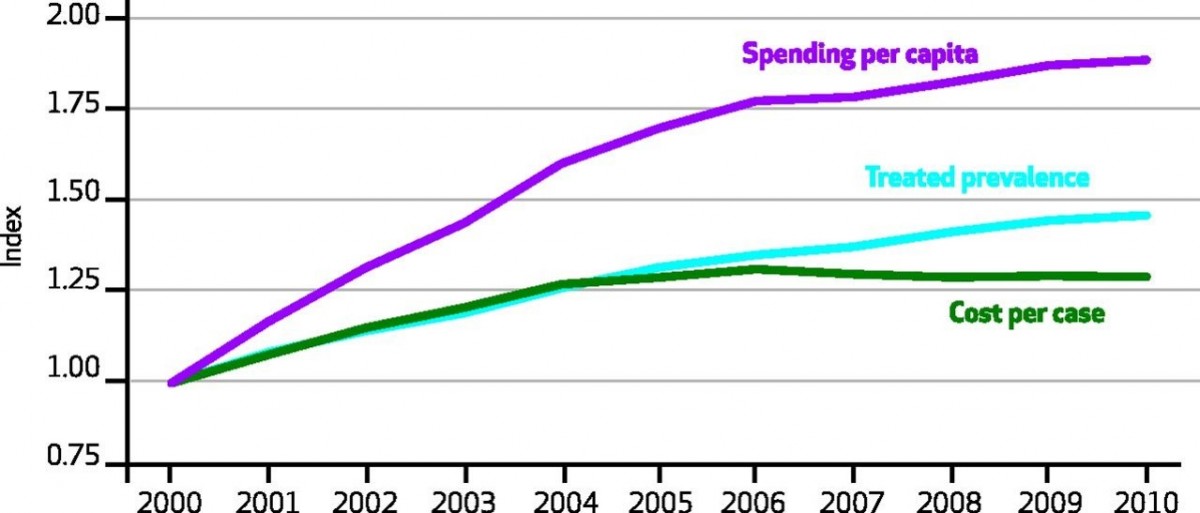

The first comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, an agency within the Department of Commerce. Using a new measure, researchers at the Bureau were able to break down healthcare spending by disease, or at least by a general category of health conditions: cardiology care, for instance, versus cancer care. They looked at two time periods: 2000-2005, a time period of high growth in spending, and 2006-2010, a time of slower growth. They tried to figure out what explained the slower growth in that time period.

Their biggest finding was that the slowing of growth did not occur primarily because fewer people got sick. Growth didn’t slow down, for example, primarily because cholesterol treatment reduced the number of people experiencing heart attacks. Instead, spending slowed mainly because the cost of treating people with problems like heart attacks stopped rising so quickly, what the researchers called the “cost per case” of treatment. Here’s a picture showing that result, with the cost per case line essentially flattening out between 2006 and 2010:

This slowdown in cost per-case spending wasn’t uniform across health conditions. Between 2006 and 2010, care for circulatory conditions grew less than half as quickly as it did between 2000 and 2005. By contrast, the rise in the cost of cancer care didn’t slow one iota over that latter time.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

The Healthcare Efficiency Myth – What Really Happens When Doctors And Hospitals Join Forces

For much of the history of U.S. medical care, hospitals and physicians have existed as separate financial entities. Physicians in the U.S. have typically been self-employed, as solo or group practitioners and not as hospital employees. An internist like me might have admitting privileges to several local hospitals. When we admit patients to one of those hospitals, we bill insurance for our services. The hospitals send insurers separate bills for hospital related expenses. Physicians and hospitals have depended on each other to conduct their business, but they have done so while largely maintaining their financial independence.

The U.S. government is trying to change that. The Medicare program is encouraging healthcare providers to consolidate forces into entities like accountable care organizations, in hopes that such integration will increase healthcare efficiency. These hopes exist because some of the most respected healthcare institutions in the country – places like the Kaiser Permanente system and the Mayo Clinic – have long integrated their physicians with hospitals. Indeed, some contend that this integration creates more efficient care.

Such integration could end up costing lots of us lots of money. When hospital and physician practices join forces, healthcare prices often rise.

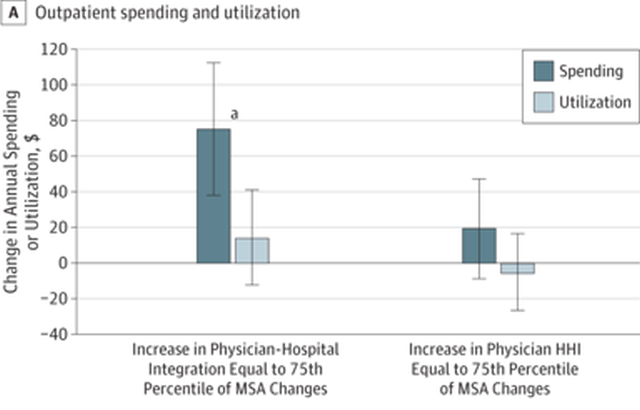

That’s certainly the conclusion of a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, led by Hannah Neprash out of Harvard Medical School. Neprash and colleagues explored what happened to healthcare spending when physicians and hospitals integrated. They discovered that outpatient spending rises as physicians gain market power through their hospital alliance. The spending increases are due almost entirely to price increases. Here is a picture of their findings. The main thing to note is that the taller bar, in each pair of bars, is the increase in healthcare prices while the shorter bar is the increase in utilization, following consolidation of physician practices and hospitals:

The tall bar on the left reflects a large increase in outpatient spending after hospitals and physicians integrate. The shorter bar right next to it reflects a modest, and statistically insignificant, increase in outpatient utilization at the same time. Spending rises while utilization stays flat – that can only happen because the price of services has gone up.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Guess Who Is Struggling to Pay Their Medical Bills!

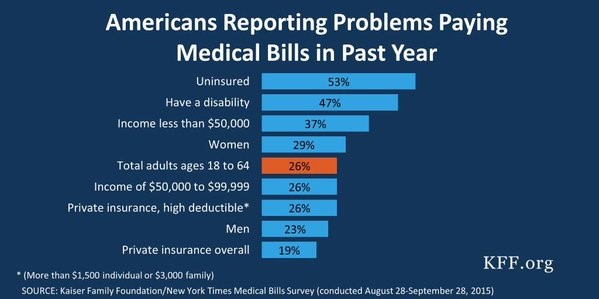

Here is a picture from the Kaiser Family Foundation showing which Americans were most likely to report problems paying medical bills last year. The sad news is that just about any way you divide it, a hell of a lot of Americans are having a heckuva time paying these bills:

Need More Evidence the U.S. Healthcare Market Is Screwed Up?

In a healthy consumer market, people compare the price and quality of goods inside whether it’s worth paying extra money to get the best possible products. In healthcare, it’s often almost impossible to figure out what things cost. And when you figured it out, the price variation often makes no sense at all – having no relationship to the quality of the good in question.

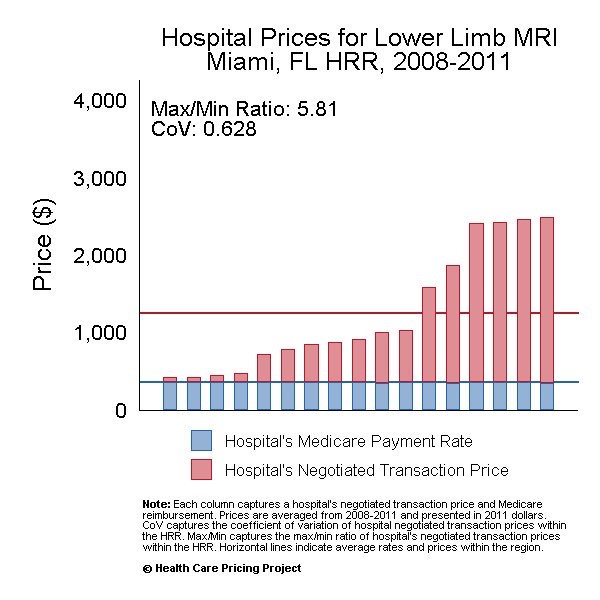

Consider this picture, which we came across thanks to @zackcooperYale. It shows almost a 6-fold variation in the cost of MRI tests in Miami, Florida:

This is not what a healthily functioning market looks like!

This is not what a healthily functioning market looks like!

An Easy (But Politically Complicated) Way To Save Billions Of Dollars On Medical Care

I sometimes worry that my wife Paula won’t be able to see me grow old. Not that I expect to outlive her. She is four years my junior and has the blood pressure of a 17-year-old track star. It’s her eyesight I’m worried about, because she is at risk for a form of blindness called macular degeneration. Paula is the youngest in a long line of redheads, several of whom have been diagnosed with this illness. Her fair-haired grandmother developed macular degeneration and was eventually unable to see her bridge hand and had to give up her golf game, just when she was threatening to score below her age. Fortunately, Paula should be able to avoid her grandmother’s fate, because we now have outstanding treatments for this disease.

Too bad these treatments are costing us billions more than they should. The price of some macular degeneration treatments is staggeringly high, and both doctors and the pharmaceutical company making the treatments are motivated to keep it that way. If we as a country want to forestall blindness in people like my wife, without going bankrupt in the process, we need to pressure our government to do some hardball negotiating.

By way of background, my grandmother-in-law suffered from what ophthalmologists call “wet” macular degeneration. Frail little blood vessels began proliferating in the back of her retina. It’s not unusual to have lots of blood vessels back in the retina. It’s that red blood, after all, that causes so many of us to look possessed in family photos, with red eyes staring demonically into the lens. But in wet macular degeneration, there’s even more blood vessels than normal in the back of the eye, and they are more inclined to leak than typical blood vessels. This leaking fluid damages the nerve cells we depend upon to see light and darkness. For years, there was little doctors could do to slow these leaks.

Then along came Avastin.

Some of you may recognize Avastin as being a cancer drug. That’s true. Avastin works by disrupting a chemical our body makes to promote blood vessel growth. Tumors that depend on new blood vessels to grow are thereby thwarted by the drug. So, too, is macular degeneration. No new frail blood vessels means no blood vessel leakage!

Many ophthalmologists treat wet macular degeneration by injecting Avastin directly into the back of patient’s eyeballs. (Under local anesthesia, of course!) And the drug isn’t even terribly expensive. By one estimate, Medicare pays about $50 a pop for monthly Avastin injections. There is a problem with this effective and affordable treatment, however. Avastin has never been approved by the FDA to treat macular degeneration. Physicians are allowed to use it as an off-label treatment, but because it is off label, it needs to be reformulated by pharmacies into an injectable form, and before standards for such reformulation were bolstered, some patients experienced eye infections from contaminated vials.

Fortunately, there is a second drug to treat macular degeneration, one very similar in its chemical composition, another blood vessel-blocking drug called Lucentis. Unlike Avastin, Lucentis is FDA-approved to treat the disease. That means it is made by the manufacturer in a ready-to-inject formulation, and there is no need for pharmacies to do any additional prepping. Lucentis is just as good as slowing the progression of macular degeneration as Avastin. There’s just one little problem with Lucentis, however. Instead of costing Medicare $50 per pop, it costs up to $2,000.

To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.

Specialty Drugs at Especially High Prices

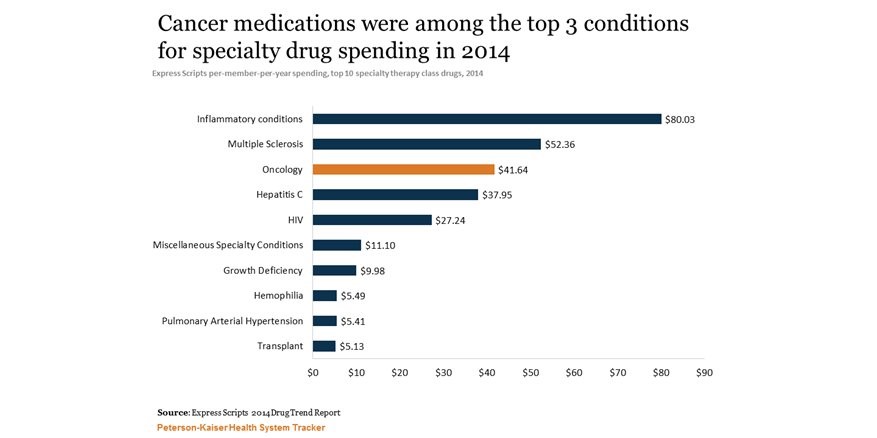

There have been many wonderful new medications in the past decade or so, drugs that finally bring hope for many people with serious illnesses like rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and even some advanced cancers. But these drugs often come at a high price. Here is a snapshot of drug spending in 2014, courtesy of the Kaiser Family Foundation:

Here's Why Insulin Is So Expensive, And How To Reduce Its Price

She drew the life-saving medication into the syringe, just 10cc of colorless fluid for the everyday low price of, gulp, several hundred dollars. Was that a new chemotherapy, specially designed for her tumor? Was it a “specialty drug,” to treat her multiple sclerosis? Nope. It was insulin, a drug that has been around for decades.

The price of many drugs has been on the rise of late, not just new drugs but many that have been in use for many years. Even the price of some generic drugs is on the rise. In some cases, prices are rising because the number of companies making specific drugs has declined, until there is only one manufacturer left in the market, leading to monopolistic pricing. In other cases, companies have run into problems with their manufacturing processes, causing unexpected shortages. And in infamous cases, greedy CEOs have hiked prices figuring that desperate patients would have little choice but to purchase their products.

Then there’s the case of insulin. No monopoly issue here – three companies manufacturer insulin in the U.S., not a robust marketplace, but one, it would seem, that should put pressure on producers. No major manufacturing problems, either. There has been a steady supply of insulin on the market for more than a half century. And there haven’t been any insulin company executives I know of who have been hustled in front of grand juries lately.

Yet insulin prices are rising to dizzying heights. In 1991, according to a recent study inJAMA, state Medicaid programs typically paid less than $4 for a unit of rapid acting insulin. After accounting for inflation, that price has quintupled in the meantime.

What explains the gravity-defying cost of insulin? I am not an expert on pharmaceutical pricing, but a few factors go a long way to explaining insulin prices. First, the insulin marketplace has been characterized by continual product upgrades. You see, there’s not just one chemical that makes up all insulin products. Instead, insulin treatments are a family of products, each with slightly different chemical makeup that influences things like how quickly the medicine is absorbed into the blood stream. Manufacturers have been toying with insulin molecules since at least 1936, when the manufacturer added protamine to insulin molecules to extend the duration of the chemical’s activity. In the 1960s, companies began synthesizing insulin, rather than harvesting it from pancreatic tissue. In the late 70s, they began producing insulin through genetic engineering.

So when I said that the price of insulin had quintupled over the decades, we have to keep in mind that today’s insulin is not the same as yesterday’s.

(To read the rest of this article, please visit Forbes.)